One year later, agency hasn’t said a word about investigation or law firm’s ‘conflict’

![]()

Sandra Shapiro and Jeffrey Mullan have been counsel to the Cambridge Redevelopment Authority and wrote a report last year concerning the agency. (Photos: Marc Levy)

It’s been a year since a lawyers’ report on the 32 months the Cambridge Redevelopment Authority went illegally without a board meeting, and despite assurances from board members and the urging of those lawyers, the report hasn’t been discussed since.

In recent months Cambridge Day has asked the agency for conversation about the report, but members of the board declined to talk, prompting the filing of a Freedom of Information request. The request, fulfilled quickly and kindly by the board and its development officer, Tom Evans, brought forward some new details about the report, including its cost and why its final form suggested a conflict of interest to members of the public but was not – in the most purely technical of ways – a conflict.

The public and city and state officials might never have realized what was happening at the authority for those 32 months had not Joseph F. Tulimieri, its executive director of more than three decades since appointment Nov. 23, 1981, crafted a deal with Kendall Square developer Boston Properties to take away nearly half of a public rooftop garden. The controversy led to the realization that there wasn’t a single active member of the authority’s board of directors, and that there hadn’t been for two and a half years.

Joseph F. Tulimieri, executive director of the authority for three decades.

That, in turn, led to the realization that Tulimieri had been setting his own pay, including his salary, retirement package and his part-time, post-retirement wage of $113 per hour. He soon resigned.

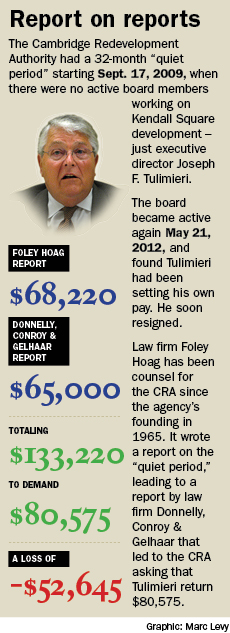

A $65,000 report from Boston law firm Donnelly, Conroy & Gelhaar demanded repayment of $80,574.87 from Tulimieri, suggesting the CRA would net back a little less than $16,000 from the former executive.

But before that came a 113-page report on the entire 32-month “quiet period” stretching from Sept. 17, 2009, to May 21, 2012, during which Tulimieri set his own rules. The report was done by three attorneys from Foley Hoag – the law firm that has counseled the agency since its founding in 1956.

Foley Hoag identified 151.6 billable hours spent writing the report at $450 per hour, for a cost to the authority of $68,220.

That makes the amount spent so far investigating that period $133,220, outpacing by far the amount the authority demanded back from Tulimieri. Evans said the auditing of agency finances from the period continues, which will raise the total.

Board expectations fulfilled

Left unanswered by either report or by the board during its yearlong silence is why the 32-month period without meetings went on unchallenged and an additional question posed by members of the public at the unveiling of the firm’s report: Why was the law firm asked or allowed to investigate a period in which its own actions – or lack of same – could be considered responsible for a costly and disturbing outcome?

Final attempts were made Wednesday to contact Tulimieri and board chairwoman Kathy Born. The messages and questions went unanswered.

A year ago, the lack of answers and attention on Foley Hoag’s role was greeted with surprise and dismay by members of the public, but Born had a different opinion: “It was exactly what we expected and very well done, and I would like to congratulate counsel on it.”

Kathy Born, chairwoman of the authority, with member Conrad Crawford. Foley Hoag lawyers communicated repeatedly with Born about the report.

The reason Born got what she expected, according to Foley Hoag’s partially redacted accounting of the hours its lawyers spent on the report, is that she and the board members talked early in the process with Jeffrey Mullan, who became primary counsel to the CRA after serving from 2009 to 2011 as secretary and chief executive of the state Department of Transportation and chairman of the Massachusetts Port Authority’s board of directors. First the CRA as a whole talked with Mullan; later the same day Born spoke with him alone about the expected “standards of [the] review.”

The lawyers spoke with Born repeatedly, but no further contact with other board members is recorded.

The full board got a draft of the report Aug. 17. The final version, error-ridden and limited in scope, was dated Sept. 12, and it was accepted (officially the board agreed to table the item) at a Sept. 19 meeting. The law firm’s work on the report ended the next day.

The FOI request turned up not a single document – no memos, e-mails or other written communications – that showed the agency or lawyers exploring or explaining a rationale for not holding monthly CRA board meetings during the period examined in the report. “CRA does not have any materials responsive to [that] item,” Evans said.

There was also nothing the agency or Foley Hoag could produce communicating with municipal officials such as the office of the city manager, which appoints four of the board’s five members, about the lack of board members or need for them.

Lawyers are on call

Evans pointed out during an informal August meeting with Cambridge Day that the agency uses Foley Hoag on a “house doctor” basis – meaning that the firm is called on for specific purposes, and does not provide overall legal oversight for the agency as its lawyers see fit.

“Foley Hoag is outside counsel to the authority, engaged to offer legal advice on specific matters,” Evans said.

For the 2.6 years or 32 months of the “look-back period” of the report, Foley Hoag has identified a dozen of its lawyers who worked with the agency, including Sandra Shapiro, who started with the authority in 1989 and continues working with it to this day, according to Evans. “For many years she served as the authority’s point of contact,” Evans said.

For the 2.6 years or 32 months of the “look-back period” of the report, Foley Hoag has identified a dozen of its lawyers who worked with the agency, including Sandra Shapiro, who started with the authority in 1989 and continues working with it to this day, according to Evans. “For many years she served as the authority’s point of contact,” Evans said.

In fact, one or more Foley Hoag lawyers, including Mullan and Shapiro, have attended every meeting of the authority’s board since Tulimieri’s deal with Boston Properties for the rooftop garden exploded into public knowledge. But “It was not the CRA’s practice to have its counsel at its regular meetings, and counsel did not typically attend meetings of the authority” before the rooftop garden issue, Evans said. “Recognize that outside counsel is only called upon to advise the authority when requested. For the time being the CRA has asked counsel to attend its regular meetings.”

The report by Jesse Alderman, Mullan and Shapiro did confirm that “at all times during the report period, Foley Hoag served as the authority’s counsel,” acknowledging that “it is uncommon for the members of such organizations not to meet regularly, as the CRA’s own bylaws require … while municipal bodies frequently have vacancies, it is unusual for an organization such as the authority to go for such a long time without any formal meeting.”

In fact, the bylaws say regular meetings will take place “at least once in each calendar month.”

At the sole meeting of that period, which took place March 17, 2010, there were three board members: Alan Bell, Mark Rogers and chairwoman Jacqueline Sullivan. The other two positions were vacant. But Rogers’ term on the board had ended three years and 10 months earlier, while Bell’s had ended eight years and seven months before the meeting. Sullivan’s term ended four months before this lone meeting, but she only resigned some months later – July 5, 2010.

“At all times during the report period, the CRA did not assemble a quorum of its members and therefore, despite one attempt to do so, did not meet, make decisions or take votes,” the Foley Hoag report says. “The actions taken in that meeting have no legal effect.”

Minutes for that meeting list no lawyer from Foley Hoag attending, and Evans confirmed from Foley Hoag that Shapiro wasn’t there.

Tulimieri had been told how to handle vacancies by Norman E. Owuellette, the records liaison officer with the state’s Executive Office of Communities & Development. On Jan. 10, 1992, Owuellette told Tulimieri that when vacancies on the board occurred certificates had to be forwarded to his office and to the supervisor of public records with the secretary of state, and that the Cambridge city clerk also was to be told “whenever a change occurs.”

As recently as 2002, Tulimieri and legal counsel from Foley Hoag were concerned about the lack of quorums and even debated the rules of members teleconferencing to attend a meeting.

Foley Hoag did serve as legal counsel for the agency during the 32-month “quiet period.” Records show the firm being paid $143,191.75 in that time. At the current rate, that would have meant some 318 billable hours of work for Foley Hoag lawyers over 32 months, or less than 10 per month.

The “house doctor” description of Foley Hoag’s work and apparent few hours the firm was called in to work suggests an answer to citizens’ obvious questions: How could Shapiro and the other 11 lawyers listed as working with the agency during the look-back period not notice there had been no meetings for 32 months in a row? Why didn’t they do anything about it?

Because of orders given to Foley Hoag by Born and the CRA, the law firm did not answer that question in its September 2012 report; because of the ensuing year of silence, there has been no explanation given since.

Conflict of interest

Martin Rosenthal, a member of the Massachusetts Bar Association’s Committee on Professional Ethics, says “There are a lot of things that are ethical but not received well by the public.”

As to Foley Hoag doing a report on a 32-month period when it appears to have enabled illegal activity by failing to ensure the CRA complied with its own bylaws – with which its dozen lawyers should have been familiar – this is not considered a conflict of interest in Massachusetts.

Technically, the term “conflict of interest” in legal ethics refers to whether a lawyer is putting a client at risk because of divided loyalties, experts said.

Even so, law experts did not see an ethical problem with Foley Hoag being called upon as the sole investigator of its own potential wrongdoing or mistakes.

In the case of the CRA and Foley Hoag, public upset “seems to be more about that this report does not appear to be unbiased and impartial, [but] I don’t see anything improper from a legal point of view,” said Martin Rosenthal, a member of the Massachusetts Bar Association’s Committee on Professional Ethics. “There are a lot of things that are ethical but not received well by the public.”

Rosenthal’s answer, condensed from a roughly 10-minute interview, in his words addressed the fact that “There are two questions here: Is it legal? And the second is, is it a good idea?”

“I’m not saying it’s a good idea. I am saying I don’t see anything illegal about it, or improper or unethical, and the standards have to do with what’s legal,” he said. “I’m not saying every law is good, I’m not saying every rule is good. But these are the rules that we have.”

The American Bar Association declined to speak at all on whether such actions were ethical.

The association first claimed only its president, at the time Laurel G. Bellows, could answer such a question. When weeks passed without answer, association spokesman Ira Pilchen finally said that among 400,000 members and staff members, “No ABA experts are available for comment.”

The association does have professional ethics guidelines, but they are simply suggestions to state jurisdictions as to how they should structure a local ethics code for practicing lawyers, said Maggie Mckinley, a social scientist and lawyer who works in the University of Chicago’s Department of Anthropology and was referred to Cambridge Day by Harvard University’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics. Massachusetts adopted the guidelines in 1997, but there appears to be no rule saying a law firm shouldn’t investigate its own actions or lack of same.

“Lawyers are unable to simply self-regulate,” Mckinley said. “They must be regulated by the state in their codes of ethics. This also means that you as a citizen of Massachusetts can change these ethical codes.”

Update on Sept. 17, 2013: Born and Margaret Drury, vice chairwoman of the board, sent a letter replying to the above article. The letter is here.

They refuse even to acknowledge the fact that one of the Authority members for several years before that was not a Cambridge resident and therefore, by my reading of state law, ineligible to serve. At the point that the fourth member left, that meant that there were only two members who actually qualified to be members, i.e., no quorum.

What are our responsible civic leaders waiting for? Why hasn’tsomeone called the police yet?

Is there any doubt that, if all the accusations about the authority making decisions, signing deals and acting without the presence of enough members to constitute a quorum–or without any members at all—there has been a serious breach of ethics and, I would think, the law. Mr. Tulimieri allegedly acted without a responsible body in place to engage in agreements for the Cambridge Redevelopment Authority, one of which gave away publicly-owned parkspace—and to feather his own nest with salary adjustments and overtime pay largesse.

If Mr. Tulimieri acted as has been reported, why hasn’t anyone working for the city called the Attorney General’s office? Is it not a crime to award yourself raises at the city’s expense? Is it not a crime to exceed your authority, cover up the absence of a quorum by acting as if there was one? And is it not a crime to award yourself pay raises and overtime pay adjustments? Mchael McLaughlin is going to jail for hiding the size of his paycheck; shouldn’t Tulimieri go to jail (or at least trial) for hiding the fact that he himself fattened his own paycheck?

And why would the city accept and pay for a report generated by the same law firm whose alleged negligence seemingly abetted Tulimieri’s crimes? Are we that willing to accept what to all spectators clearly appears to be a whitewash?