Housing Authority 9,500-person wait list will freeze for upgrades; few rents to rise (update)

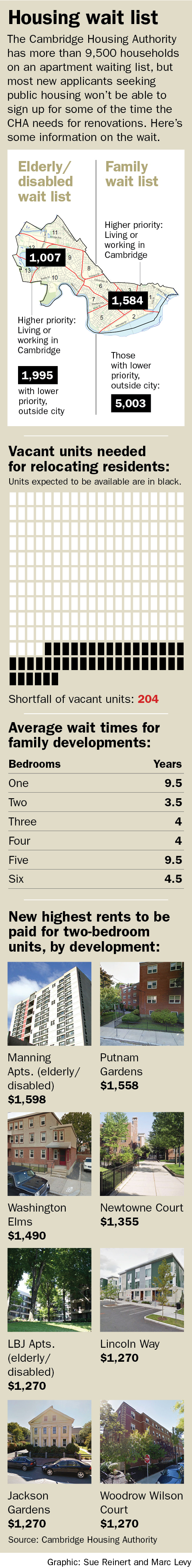

The Housing Authority’s huge redevelopment project to preserve low-income housing means that most new applicants seeking public housing won’t be able to sign up, and the more than 9,500 households already on the waiting list probably won’t get an apartment for an unknown length of time, officials say.

The Housing Authority’s huge redevelopment project to preserve low-income housing means that most new applicants seeking public housing won’t be able to sign up, and the more than 9,500 households already on the waiting list probably won’t get an apartment for an unknown length of time, officials say.

The authority is closing the public housing waiting list to all but emergency applicants, and not moving people on the list into vacant apartments, because it needs a stockpile of empty units for tenants who will be temporarily displaced by three to five years of construction, Deputy Executive Director Michael Johnston said in a memo last month. Executive Director Gregory Russ said vacant units will be “held for relocation” for at least the first one to two years of work.

Russ noted that the authority already doesn’t take new applications for one-bedroom apartments. The waiting list for another source of low-income housing, Section 8 vouchers that help pay rent in private housing, has been closed for years because of shrinking federal aid.

At a meeting held the Tuesday before Thanksgiving, authority commissioners approved closing the entire public housing waiting list by Jan. 1. In another unexpected action stemming from the long-sought redevelopment, commissioners also approved raising rents for a tiny portion of current tenants under the new financing arrangement that will pay for the $360 million project.

The authority has been trying to find money to rehabilitate its aging public housing portfolio for years as officials warned that the units could become uninhabitable if they continued to deteriorate. With federal funds drying up, officials turned to private financing, but still needed government approval, which came last December.

The move puts all public housing developments in Cambridge under private ownership – on paper – by transferring them to nonprofit agencies controlled by the authority. Loans and investments by some of the largest financial companies in the country will help pay for construction.

But now it appears that the effort to preserve housing that serves the poorest residents of high-rent Cambridge will reduce opportunities temporarily for low-income people who aren’t in public housing now. Russ acknowledged the “interim trade-off,” but said that without the redevelopment, “these properties could eventually be lost as a resource.”

Applicants for public housing now wait almost 20 years for a one-bedroom apartment at the Putnam Gardens family housing development, Russ said. He estimated that average wait times across all family developments range from 3.5 years for a two-bedroom unit to 9.5 years for one bedroom; and for elderly developments, 1.5 years for a studio to 2.5 years for a one-bedroom unit.

Neither closing the waiting list nor the rent increases were discussed at numerous public hearings and meetings on the construction plan. Russ said closing the waiting list “is not a surprise” because “we have said all along that these capital improvements would require a large relocation effort, and that means moving residents around rather than placing new applicants from the waiting list. Leaving the lists open and giving false hope would not be productive or fair.”

Rent increases

As for rent increases, authority officials assured residents repeatedly that their rents would not change under the new financing system. Now the authority plans to raise rents for 72 of the roughly 2,500 families in public housing; officials say the changes will be discussed at a public hearing Thursday.

The increases apply to “ceiling rents” paid by the highest-income residents. Tenants must meet income limits to move into public housing, but, once they’re in, they can stay if they earn more. Residents generally pay 30 percent of their income as rent, up to the “ceiling rent.”

If their income rises high enough, the ceiling rent may represent much less than 30 percent of earnings.

Ceiling rents now vary depending mainly on the size of the unit, Director of Property Management James Comer said. The lowest is $915 for a studio, and the highest is $1,495 for five bedrooms, Comer said. The new ceiling rents will also vary, by development and apartment size, and will increase significantly for some families: Three affected households face an increase of $624 a month, Comer said.

That sounds “burdensome” in dollars, but those families now pay rent of only 10 percent, 13 percent and 18 percent of their incomes, Comer said. After the increase, they will pay 15 percent, 19 percent and 26 percent, which “still [doesn’t] bring about a level of equity with their very low-income neighbors who pay 30 percent” of income, he said.

Although families paying ceiling rents earn far more than most public housing residents, they still may not be able to afford private housing in Cambridge, where middle-income people complain about being priced out of rentals and homeownership.

At least three years’ warning

Comer said CHA decided to impose the higher rents to increase revenues needed to pay for the construction project, to reduce disparities and to address conflicts between rules for private funding sources and public housing rent-setting procedures. Officials didn’t realize the full extent of the problem until September, he said.

Families will have at least three years and possibly more before they must pay the full increase, although they must start paying part of the higher rent earlier. The 72 families now pay from 8 percent to 28 percent of their income for rent; after the increases they will pay 12 percent to 30 percent, Comer said.

About 70 percent of the affected families – 51– live in the Washington Elms and Newtowne Court developments, side by side in Area IV between Central and Kendall squares. Most of the 72 households are in two-bedroom or three-bedroom apartments. Ten families are headed by someone over the age of 65, Comer said.

Two years ago the authority adopted a policy intended to persuade the highest-income families to leave public housing by offering them one-time payments if they moved out within four years, with the threat of charging them close to market rents if they stayed longer.

The rule has not been enforced, and Comer said that because of broad changes required by the redevelopment effort “we will defer this for the near term.”

This story’s graphic was updated Dec. 10, 2014, to show that high priority and low priority for the housing wait list is based on whether applicants are in or outside the city.

The national Fair Market Rate for a 2-bedroom apartment is $949. In Cambridge, as of last year’s CDD survey, the median 2-bedroom apartment rented for $3,000. In other words, these new ceiling rents still represent 50% discounts on the market rate of housing for the fortunate few families who will be paying them. And they’ll be paying far less, as a percentage of their income, than their neighbors in or outside of public housing.

The more disturbing question relates to the 9,500 names on the public housing waitlist, and the thousands who have Section 8 vouchers but have to use them outside of Cambridge, are on the Section 8 waitlist, or can’t even get on it because it’s closed.

That’s an enormous backlog. Every one of those families represents substantial loss and suffering.

We can build more public housing – except that we can’t seem to find the funds to maintain the units we have without playing financial shell games, and federal support is declining. We can use inclusionary zoning ordinances, but stacked against the enormity of the need, a few dozen, or even a few hundred, new units seems paltry.

Or? We can add thousands of additional units to the Cambridge market in market-rate developments. Even adding as few as six hundred new units would likely arrest the climb in rents. Adding thousands? It’d relieve the pressure that’s slowly squeezing diversity of all kinds out of this city. Fewer families would need to rely on public housing, because they’d be able to afford market-rates for older housing stock renting below the median. Those who qualify for Section 8 vouchers might actually be able to use them. We might be able to reopen the waiting list.

But all new construction in this city instantly runs into opposition to gentrification and hostility to change. We need a spine of towers running along Mass Ave, where infrastructure can support them, adding thousands of new units. The next time you hear someone inveighing against a proposed development? Think of the 9,500 families that can’t afford their own city.

Commenter, can you cite any real world instances where your prescription has actually worked? What we have seen here and in other high-demand, high-price locations is that building so-called market-rate housing with a soupçon of subsidized units for lower income residents raises the rents of the existing housing around. In other words, it raises what counts as market rate for housing. See, for example, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2014/10/de-blasios-doomed-housing-plan/.

That article isn’t exactly compelling and some of the prescribed “fixes” to the inclusionary program in New York are already part of Cambridge zoning law. Further the author provides no actual proof of the results he states “might” happen. Additionally the New York law seems to advocate tearing down existing housing stock and beloved rent controlled units in favor of denser projects that add a formulaic approach to lower, middle, and market rate units. You don’t really see that happen in Cambridge. Most new housing projects have been on previously commercial/industrial parcels or vacant lots (another prescribed method of building in the cited article). I would also add that rents have continued an upward tick in areas with no housing being built at all and some of our least dense and probably best locales for creating ample density are preserved as monuments to poverty and antiquated notions of how poor people aight to live…isolated and kept apart from the general population. There has to be some middle ground between ultra high dense construction and the urban sprawl anti-development types seem to be advocating for.