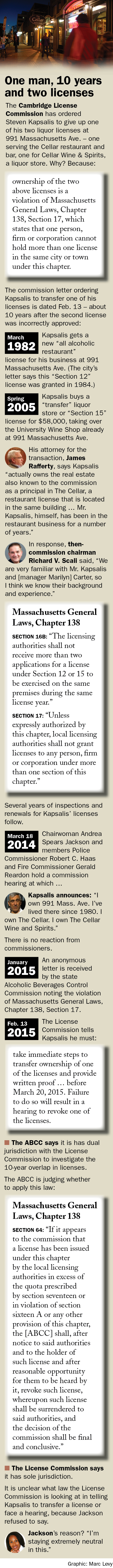

Decade after okaying illegal liquor license, board corrects its mistake – incorrectly?

A business granted an improper license by city and state officials a decade ago has been approved for renewals of the illegal license every year since, even while those city officials rejected similar applications.

A business granted an improper license by city and state officials a decade ago has been approved for renewals of the illegal license every year since, even while those city officials rejected similar applications.

The owner of the business – Steven Kapsalis, owner of the bar at 991 Massachusetts Ave., as well as the Cellar Wine & Spirits store and Garden at the Cellar restaurant space – is facing no punishment, and this is not the first time the License Commission has displayed a uniquely credulous or sympathetic relationship with him.

Last year, he urged the same commissioners who have been approving his illegal dual licenses to reject a wine bar and charcuterie called UpperWest that was proposed for nearby, arguing that approving it would be “directly hurting me.”

The commissioners agreed with the owner’s request not to have competition, raising bizarre objections that led to the withdrawal of the UpperWest application. “I can’t see myself voting for an all alcohol license at this location,” said commissioner Gerald Reardon, the city’s fire chief, in comments echoed by License Commission chairwoman Andrea Spears Jackson. “You’ve got a lot of people around you that have paid a lot of money for these licenses, and it devaluates their license.” (The couple behind UpperWest, Kim Courtney and Xavier Dietrich, declined to comment for this story, citing a pending criminal investigation.)

The problem? Kapsalis has what’s called a Section 12 alcohol license for a restaurant going all the way back to 1982, a new license for which he wouldn’t have paid anything, and in the spring of 2005 also applied for and got a second, Section 15 license for a liquor store on the same premises. State law says that’s not allowed.

A decade later, after Kapsalis’ objections to UpperWest were joined by another man’s apparently false petition (resulting in an arraignment on charges of forgery) and the state Alcoholic Beverages Control Commission reported getting an anonymous letter pointing out Kapsalis’ own dual-license problem, the city is acting.

Unidentified law

In a Feb. 13 letter from Elizabeth Lint, the commission’s executive director and counsel, Kapsalis is told he must “take immediate steps to transfer ownership of one of the licenses” before March 20, because “failure to do so will result in a hearing to revoke one of the licenses.”

It’s not at all clear that’s what the applicable law says, though.

A state law about licenses issued in violation says the Alcoholic Beverages Control Commission “shall, after notice to said authorities and to the holder of such license and after reasonable opportunity for them to be heard by it, revoke such license, whereupon such license shall be surrendered to said authorities, and the decision of the commission shall be final and conclusive.”

When asked Tuesday to identify the law the commission looked to in deciding a course of action, Jackson refused to answer. “I’m staying extremely neutral in this, so that’s something you’re going to have to look for,” the chairwoman said. “I’m not giving any response as it relates to this. It’s a matter that’s under review.”

Chandra Allard, communications director for the State Treasury, said the ABCC shared dual jurisdiction on the case with the commission and was investigating on its own. “We are definitely looking into it,” Allard said.

That conflicts with Lint’s take on the situation: that the commission has sole jurisdiction in the case, and that the city and state bodies can’t act simultaneously.

What commissioners missed

“This is not an unusual situation. It has happened a few times before,” Lint said, referring to one person getting dual licenses. As to how it occurs, she called that a “really good question.”

Lint wasn’t with the commission when it granted Kapsalis his second license March 29, 2005, transferring one from University Wine Shop at Harvard Square to Kapsalis’ Kapsco Inc. and manager Marilyn Carter.

Commissioners missed inaccuracies on the license application, which asked whether the applicant owns the premises where the license will be used. Kapsalis marked “no,” but the city’s property database shows he has owned 991 Massachusetts Ave. since January 1981. Kapsalis’ attorney, James Rafferty, boasted to commissioners during the meeting that Kapsalis “actually owns the real estate” as well as lives there.

Commissioners also broke with convention by asking no questions about the backgrounds of either Kapsalis or Carter.

“We are very familiar with Mr. Kapsalis and Ms. Carter, so I think we know their background and experience,” said the commission’s chairman at the time, Richard V. Scali.

Seemingly obvious

Commissioners even talked about how Carter would divide her time between the two licensed businesses, a seemingly obvious sign of the conflict causing the city to take action 10 years later.

Somehow, neither the commissioners nor Rafferty – a Cambridge attorney with extensive experience in licensing matters – acted to prevent the conflict.

Rafferty didn’t return messages left Monday and Tuesday.

License Commission and ABCC officials were contacted in researching this article, as well as city councillors, city managers and lawyers for Kapsalis. Carter, speaking for Kapsalis, twice declined to talk or even entertain questions, despite being told their lawyer had not returned a request for information.

Both businesses have been inspected throughout the past decade for compliance with the law, and their licenses have been renewed annually. Inspections have been done by longtime investigator Henderson Headley and Andrea Boyer, the chief licensing investigator for the commission since 1993, but Boyer said the investigators’ role didn’t include licensing and other paperwork, and that “anything dealing with applications or other paperwork is through the executive director,” a reference to Lint.

Last year, at a hearing held March 18, Kapsalis began his testimony to Jackson, Reardon and Police Commissioner Robert C. Haas by announcing loudly the problem they are addressing roughly a year later: “I own 991 Mass. Ave. I’ve lived there since 1980. I own The Cellar. I own The Cellar Wine and Spirits.”

Familiarity with the law

Once again, the commissioners didn’t even blink.

Yet they showed a familiarity with the law and an interest in applying it to others before and after the hearing. At a meeting two months later for Shepard, a restaurant going into the Chez Henri space near Harvard Square, Jackson flagged the issue as a problem to be dealt with by owner Rene Becker before licensing. The resolution was for Becker to transfer ownership of a license at his Hi-Rise Bread Company to his wife before formal commission approval. Again in June, the commissioners flagged the ownership of two licenses as a problem, this time for Amrik Pabla of Libby’s Liquors, Dosa Factory and Bao Nation – as well as an upcoming Central Square revival of Boston’s Mantra restaurant.

“What is disturbing to me is that we been have down this road … it had to be, what, two or three years ago we went through this process,” Haas told Pabla and his lawyer, referring to commission business in 2008. “We had the discussion before because he couldn’t own a restaurant and have a package store … He has been a businessman in this community a long time and he should understand what the regulations are.”

“It was absolutely disclosed”

Lint, the commission’s executive director, noted that the problem with Kapsalis’ licenses should have been just as obvious to the state. “The ABCC didn’t flag it either, and it was absolutely disclosed on the application,” she said.

“Whoever voted made a mistake,” Lint said. “I don’t know what to say.” (Listed as being at the meeting were Scali, Deputy Fire Chief Daniel Turner, police Capt. Henry W. Breen and Ellen Fitzgerald Watson.)

At the state level, Allard said ABCC officials couldn’t talk about the case until their own investigation was complete, including an opinion on whether local officials were taking the right approach to resolving the conflict.

She also couldn’t guarantee the agency would take action, but said generally that the state serves as a check and balance to local enforcement.

“There are times the local authorities don’t always address the law [properly] and we have to step in,” Allard said.