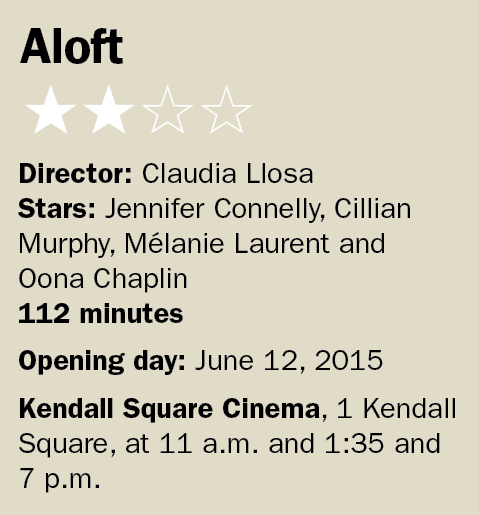

‘Aloft’: Cast keeps healing journey tethered when dreamlike concept aims a bit too high

Much of what transpires in “Aloft” washes over you like a dream with peril and anguish looming at the corners, ever ready to swell and flood Claudia Llosa’s delicate drama. It’s more a sensual experience than a narrative, per se; and while the dystopian prognostication boasts a concrete plot – or two – Llosa has loftier, more transcendental ambitions. Think “The Tree of Life” or “Life of Pi,” but Llosa’s film, airy and full of flight, never quite spreads its wings.

Set somewhere in a slightly alternative reality, in the near future, in a place that’s rooted very much in the here and now, “Aloft” centers on a French journalist (Mélanie Laurent) making a documentary about a reclusive female faith healer living on a frozen lake in the arctic north. To gain passage she connects with a troubled falconer (Cillian Murphy) with ties to the healer, who can harness the power of nature to cure terminal illnesses. Given that such skills in a traditional office park might elicit long lines and cause traffic headaches, the tough-to-reach outpost somewhat makes sense – though, if it’s such a bitch to get to, might not the dying and the needy expire long before arriving at doorstep of salvation?

Set somewhere in a slightly alternative reality, in the near future, in a place that’s rooted very much in the here and now, “Aloft” centers on a French journalist (Mélanie Laurent) making a documentary about a reclusive female faith healer living on a frozen lake in the arctic north. To gain passage she connects with a troubled falconer (Cillian Murphy) with ties to the healer, who can harness the power of nature to cure terminal illnesses. Given that such skills in a traditional office park might elicit long lines and cause traffic headaches, the tough-to-reach outpost somewhat makes sense – though, if it’s such a bitch to get to, might not the dying and the needy expire long before arriving at doorstep of salvation?

In a separate spindle, some 20 years earlier, a single mother (an angular and alluring Jennifer Connelly, sporting a rat tail) toils on a pig farm raising two boys. The youngest is sick and without much prospect, while the older puts his feeble brother constantly at risk (such as by joy-riding in a pickup truck on thin ice). Connelly’s Nana, desperate, turns to a New Agey sect, where the head, considered a drunkard and a charlatan by nonbelievers, is rumored to, with twig and twine, remedy those doctors have closed the book on.

The interweave between the two threads is laid with overt purpose, but not much else is. The raw, enigmatic aesthetic rides artily along the rails of cinematographer Nicolas Bolduc’s crisp, ethereal rendering of the great white North, but as the film rises to tighten its broad thematic net, there’s a sudden, unsavory triteness – a push and pull on the viewer’s sensibilities, if you will. Llosa, who hails from Peru and is making her first English-language production, has long been focused on the cult of motherhood and the sorority of the oppressed; “Madeinusa” (2006) told the tale of a girl coming of age in a remote village, while “The Milk of Sorrow” (2009) connected the plights of sexually abused women. Her aim is noble and much needed in an industry where the feminine voice is defined by the sole female possessor of the Oscar for Best Director, who makes movies about men in war; but still, the elements of storytelling and the elaboration of motif and origin of emotional turmoil should not be left to hang in the air as wispy vagaries.

Llosa’s best asset, beyond Bolduc’s sure eye, is her sharp cast. Connelly harnesses restrained resentment with grit and earnestness, as do Laurent and Murphy with their luminous watery blue eyes casting forth vulnerabilities while masking alternative agendas. There’s a certain poetic bravado to the trio’s collective power of rue, but to what end? With the stakes so high, so early, the degree of difficulty further handicaps a story leaden with ideas and in search of a form.

Tom Meek is a writer living in Cambridge. His reviews, essays, short stories and articles have appeared in The Boston Phoenix, The Rumpus, Thieves Jargon, Film Threat and Open Windows. Tom is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics and rides his bike everywhere. You can follow Tom on Twitter @TBMeek3 and read more at TBMeek3.wordpress.com.