Campaign finance reform responsibility returns resoundingly to city councillors

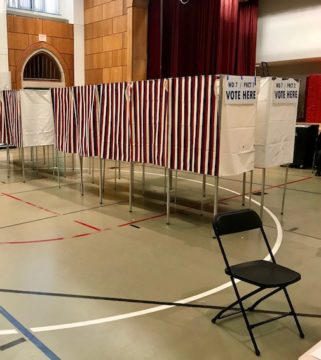

The Nov. 7 municipal elections could be the last without public financing of candidates. (Photo: Marc Levy)

The hot potato of campaign finance reform got tossed back to the City Council on Monday with what seemed like a game-winning flourish.

“We responded to this same basic issue in 2014 and 2016, and now we’re basically responding the same way,” City Solicitor Nancy Glowa told councillors. “Each time, we’ve said we need guidance from the council … These are significant policy issues for the City Council to give the administration guidance and direction on how you would like such a thing to be shaped.”

“We really need to hear from you,” Glowa said. “Really, respectfully, it needs to come from the council.”

In the most recent attempts to look at relieving candidates of fundraising burdens and avoiding controversies over donations from sources such as real estate developers – housing and development being the most contentious and divisive issues in Cambridge politics – councillors asked the City Manager’s Office for a similar report on legal campaign finance options Oct. 31, 2016.

When nothing was heard and the order was all but forgotten, a citizens group tried to put a nonbinding question about public campaign financing on November’s municipal ballot, only to see it apparently killed by councillor Leland Cheung, revived by a quirk of municipal law and then set aside again by councillors again seeking word from the city manager. Reminded there was already an order awaiting action, they set a deadline for the end of October.

State-level advice

The deadline was missed. But the report made that extra couple of weeks seem of little importance.

The Attorney General’s Office said that the state’s constitution prohibits municipalities from passing laws that “regulate elections,” Glowa said, and the city would be “well-advised” to get special home rule legislation to implement public funding for local candidates. The state Office of Campaign and Political Finance and the Director of Elections in the Office of the Secretary of the Commonwealth confirmed the advice.

No city or town in Massachusetts has yet taken the step.

Councillor Nadeem Mazen probed Glowa for a sign that funding of candidates wouldn’t be considered as regulating an election, which would avoid the need to go to the Legislature, but she didn’t agree and suggested courts wouldn’t either.

“We typically would follow the guidance of the attorney general,” Glowa said.

Changing leadership

Next Mazen pondered the consequences of going ahead anyway. “They would never say, ‘Go for it’ … I’m not asking whether the attorney general would like us to be conservative and safe. I’m asking would the attorney general sue us?” he asked. “Frankly, I’m not reading in their response that they’re taking such an aggressive stance.”

But with only a month and a half remaining of the term before he leaves to run for the U.S. House of Representatives, Mazen’s hint of rebellion will almost certainly not be a factor in the council’s next steps. Cheung, the most outspoken voice against municipal campaign finance reform – on the basis that the implication of corruption is insulting – is also leaving the council.

Deciding on an approach to public financing demands more public input, either through public meetings or surveys, Glowa said.