Buses will be back for 11 months at Lechmere as green line extension T project rolls onward

Brittany Bradley, a Somerville resident who works at MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, talks Tuesday at a green line extension project meeting about relentless construction noise. (Photo: Marc Levy)

Before a relocated Lechmere light rail station opens in December 2021, residents can expect 11 months of bus service to replace trains starting in May, state transportation officials say.

The buses will shuttle between Lechmere and North Station – something that will feel familiar to residents from when trains were shut down from April to November 2011 for construction at the line’s Science Park station, and before that from June 2004 to November 2005 for track replacement and new signal systems.

It could have been worse. When the green line extension was planned to be complete in mid-2017, before a funding scare that nearly canceled the entire project, shuttles buses were expected to run for at least a year, and potentially several months longer.

There was a bit more news learned Tuesday by some 150 residents at a green line extension project public meeting at the East Somerville Community School, including that a developer-funded elevator will be added to the planned Union Square green line station. That will help avoid an extra 120 yards of ramp travel to get to the T when approaching the station from the Cambridge side.

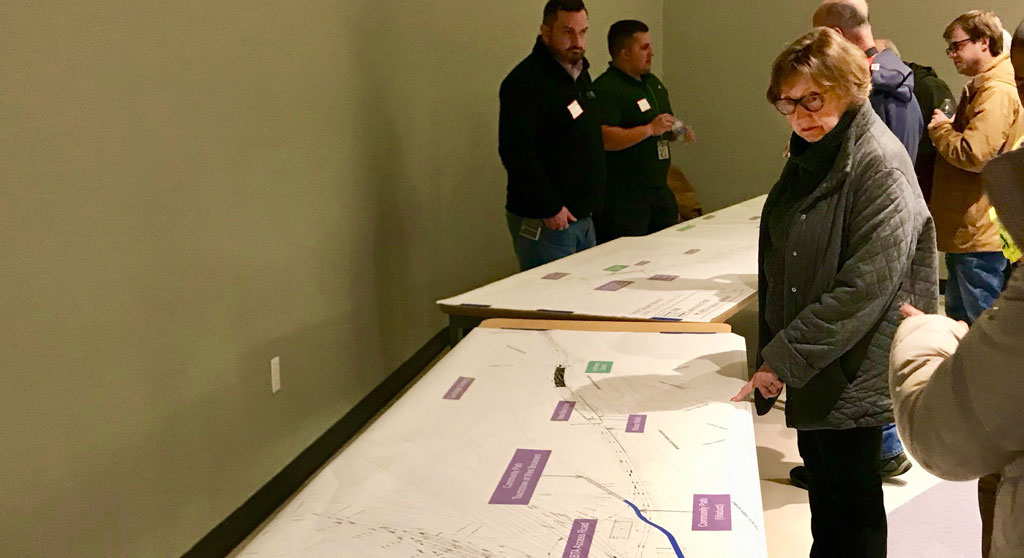

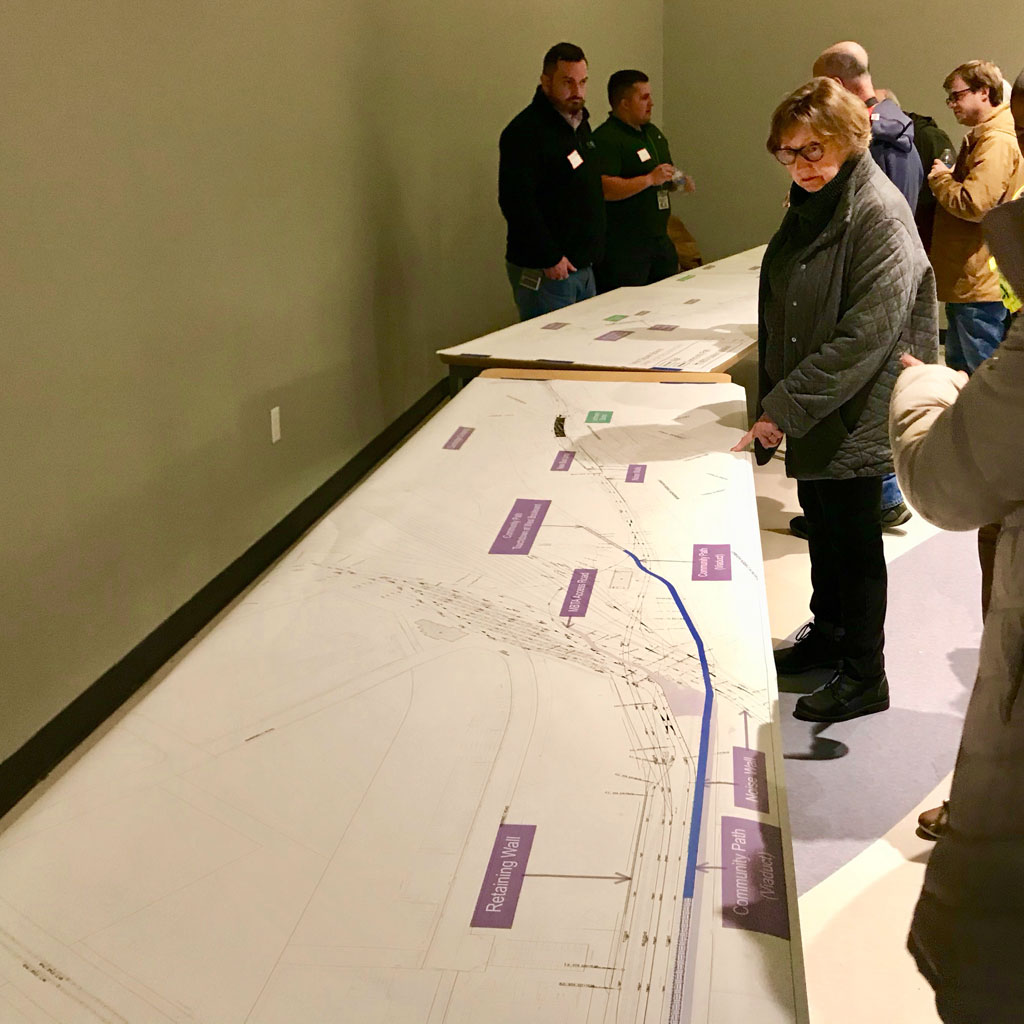

Residents look over plans for a multiuse path accompanying a light rail project on Tuesday at the meeting, held at a school in East Somerville. (Photo: Marc Levy)

While the elevator is a “done deal,” according to a state transportation staffer at the early, open-house portion of the meeting, it may follow the opening of the station.

And at least the project as a whole is “still very much on target,” said Terry McCarthy, deputy program manager for the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority. That means it’s making up time in one area if it loses time in another – such as at the Ball Square bridge in Somerville, one of only several bridge shutdowns in a city where traffic relies on them. There and elsewhere along the route, contractors are digging to place hundreds of pylons for the 15 percent of the project that will be elevated on viaducts, and workers often encounter “surprises underground” such as more rock than expected, officials said.

The project also included the massive feat of relocating tracks for the Lowell commuter rail line to install drainage that will prevent flooding expected from worsening climate, then moving the tracks back to make room for the green line trains that will run alongside. While the relocation started in October 2018, moving the tracks back begins this weekend north of College Avenue. A multiuse path will run by both sets of tracks, mainly above their sunken corridor. It was this work raising concerns in August that the project was falling behind by two months, but officials said then and on Tuesday that there was no reason to worry.

Extending from the extension

During the 11-month shuttle-bus period at Lechmere, the project plans to sneak in a five-month viaduct improvement project that will not affect finish dates, McCarthy said. Still, East Cambridge residents can expect to live with construction for a long time: It is only after the new Lechmere station opens, moved across Monsignor O’Brien Highway to Cambridge Crossing, that work will begin developing the newly empty Lechmere Square. (A decade ago, plans included a 12-story hotel; a commercial building of up to four stories, with retail or restaurant space at ground level; and between those a plaza and year-round, 30-stall public market under a refurbished T garage roof.)

In addition to the Lechmere work, the $2.3 billion, 4.7-mile green line extension will add five stations along a Medford branch and a one-stop spur to Union Square. Daily ridership is expected to be 45,000 by 2030 in two dozen new train cars – nine of which are already here, according to John Dalton, program manager for the project.

The work has been done with later public transit expansions in mind, MBTA officials said. The multiuse path is being built so as not to preclude connecting it later with the Grand Junction multiuse path in Cambridge and to the Twin Cities Plaza in Somerville; and work on the T is being done to make possible a further stop to Route 16 in Medford – part of the original, eight-stop plan for the extensions – and a green line link to the red line Porter Square T stop.

But nerves are already fraying from the construction, and not just because of traffic patterns shifting from bridge closings.

“I haven’t slept”

During a Q&A period that closed out the night, Somerville resident and Massachusetts Institute of Technology employee Brittany Bradley played a recording of the nerve-wracking grind of construction coming from outside her home – at 2 a.m. “It was inside my house that I recorded this, so as you can imagine, I haven’t really slept in the past month,” Bradley said. “When I talked to folks from GLX, they said none of the loud work would happen after 10 p.m. Well, that is untrue, and I’m sure any of my neighbors here can attest to that.”

“They tell me two more weeks, two more weeks – I can’t last two more weeks,” Bradley said.

Extension officials said they were helpless, as the work must happen on nights and weekends when the T and commuter rail isn’t running to prevent even more disruption to commuters’ schedules. “It’s the only way we can get the project done,” McCarthy said.

State Rep. Denise Provost said she had argued for the project to find and pay for Airbnbs for the closest neighbors to the loudest work as “the least that they can do,” but was told green line extension officials didn’t have the authority.

Also attending were state Reps. Mike Connolly and Christine Barber and state Sen. Pat Jehlen, with Connolly staying to the end and offering to hear from affected residents to see if he could further the talks. (Also attending: transportation directors Joseph Barr, from Cambridge, and Brad Rawson, of Somerville.)

Different ways of building

Connolly worried that the state was moving toward a “design-build” process for projects beyond the green line extension, which means the same people are in charge of design and construction. That decreases creativity and input from the community “because they’re looking at state specifications and thinking, ‘Okay, what is the most economical way to meet those specifications, in a minimum way?’ When a resident comes forward and says it’s not working, they’ve already decided that’s how they’re going to make their profit,” Connolly said.

The original version of the green line extension was scuttled when it was reported in 2015 that costs were more than $1 billion over an expected $2.2 billion. Although the project was a legal requirement resulting from Boston’s Big Dig, it needed Cambridge and Somerville to chip in – $25 million and $50 million, respectively – even for bare-bones stations from the design-build GLX Constructors firm.

Dalton, who has been with the state only for the second attempt at the extension project, said the problem the first time around resulted from “the way the contract model was set up.”

“It was kind of case study in ‘scope creep,’ where the project requirements aren’t really defined in the full funding grant agreement – the contract the Federal Transit Administration had with the MBTA just said, ‘We’ll give you this money as long as you build this thing,’ and the requirements were pretty basic. It was like, ‘Build a station’ and not much more than that,” Dalton said. “The scope evolved dramatically away from a base requirement. And when you priced that evolution that included a lot of extra stuff, it drove up prices way beyond what was affordable.”

The contractor had seven bidding packages, and as they started to come in, “they’re all a little bit over budget, and kind of trending in a concerning way,” Dalton said. “Then the fourth package came in, and it was like – you know, ‘Wow, we gotta stop.’”

The full funding grant agreement provided for an offramp that meant the project could be halted upon identifying projected overruns, and before there were actual cost overruns. “That’s a big, big, big, big difference,” he said. “The money wasn’t spent.”

In a way, the system worked as it was meant to, and not just because it stopped before actual overspending occurred. “There are a lot of people who were on the project then” and aren’t now, Dalton said. “Were they held accountable? You know, I guess one could argue that way.”