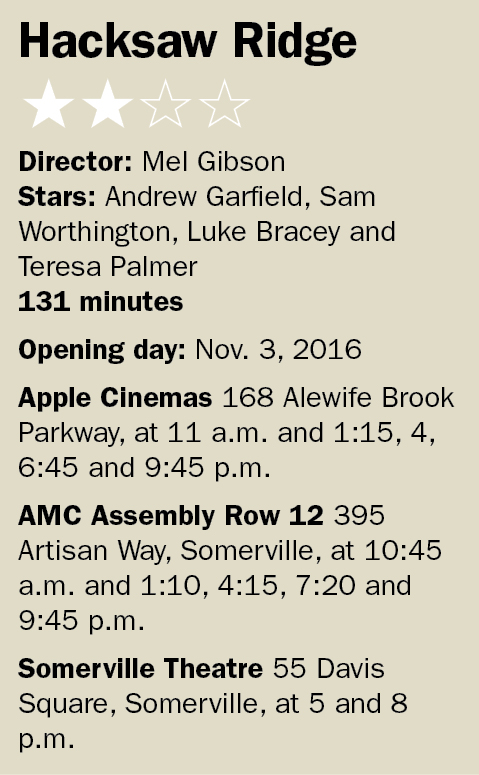

‘Hacksaw Ridge’: Mel’s tale of nonviolence is at war with self, a message soaked in gore

https://youtu.be/9BqgHYLvHIE

“Hacksaw Ridge” sees Mel Gibson return to directing for the first time in more than 10 years, and while some may find satisfaction thinking of it as a visceral action film, the predominant sense it leaves is of wasted opportunity – of how great this film could have been with a touch of nuance.

It’s based on the true story of Desmond Doss (played with aw-shucks charm by Andrew Garfield), who enlisted in World War II as a conscientious objector, refusing to pick up a weapon because it conflicted with his beliefs. He instead chose to use his medical skills to save soldiers. Of course he’s immediately met with pushback, with higher-ups believing he cannot protect the men around him without using a weapon, but he stays true to his faith and ultimately saves countless lives during the titular battle. A naturally intriguing story, especially when cast against typical war-movie fare, it’s the moments that makes Doss a name worth recognizing that showcase just how much stronger “Hacksaw Ridge” could have been had it been unburdened of Gibson’s heavy-handedness.

It’s based on the true story of Desmond Doss (played with aw-shucks charm by Andrew Garfield), who enlisted in World War II as a conscientious objector, refusing to pick up a weapon because it conflicted with his beliefs. He instead chose to use his medical skills to save soldiers. Of course he’s immediately met with pushback, with higher-ups believing he cannot protect the men around him without using a weapon, but he stays true to his faith and ultimately saves countless lives during the titular battle. A naturally intriguing story, especially when cast against typical war-movie fare, it’s the moments that makes Doss a name worth recognizing that showcase just how much stronger “Hacksaw Ridge” could have been had it been unburdened of Gibson’s heavy-handedness.

Religion, key to Doss’ story, can be represented in film with subtlety and beauty, but instead of allowing his faith to add to who Doss was as a person, it is instead used as both his defining quality and the film’s. The depiction of how Doss used faith to overcome exhaustion and terrible odds is effective; Gibson’s gratuitous shots painting him as a Christ figure, whether in an obvious and embarrassing shot of Doss being baptized or him hanging mid-air, palms up and bloodied as if he were lying crucified on a cross, is repellent. And there’s only about 20 minutes of the film that doesn’t just see another Christ figure onto which Gibson can project his fanatical idealism.

Garfield, though, is wonderful, especially in quieter, introspective moments where we can sense the weight of his decisions. More than anything, this is a simple reminder of Garfield’s talent and a nice primer for what should be an excellent turn in Martin Scorsese’s “Silence.” Hugo Weaving also impresses as Doss’ father, seemingly suffering from then undiagnosed PTSD. Teresa Palmer is all but background draping in a thankless worried-wife role, and Vince Vaughn is distractingly miscast.

The script, by Andrew Knight and Robert Schenkkan, is an even more glaring flaw; in the first half it hits nearly every well-worn beat of a war biopic, forgoing innovation for paint-by-numbers familiarity. Later, it contributes to Gibson’s abhorrent and dehumanizing portrayal of the opposing Japanese soldiers with an exploitative seppuku sequence that’s as heinous as anything on screen this year.

It all comes back to Gibson, whose ideals are clearly in conflict with how he shoots the picture. His depiction of the Japanese soldiers is clueless enough – depicting their assault in the same way Marc Forster shot angry mobs of zombies in “World War Z,” and with as little empathy. Gibson depicts Doss as a saint for staying true to his nonviolent beliefs, yet gives us violence and gore in gleeful slow-motion sequences of bullet-ridden helmets, burning, writhing bodies and lost appendages. Doss’ motives and beliefs are always clear and determined, the director of his biopic less so – it’s never quite clear what film he’s trying to make, who it’s about and who it’s for.

“Hacksaw Ridge” will satisfy Garfield fans, Gibson supporters or war movie connoisseurs, but little more.