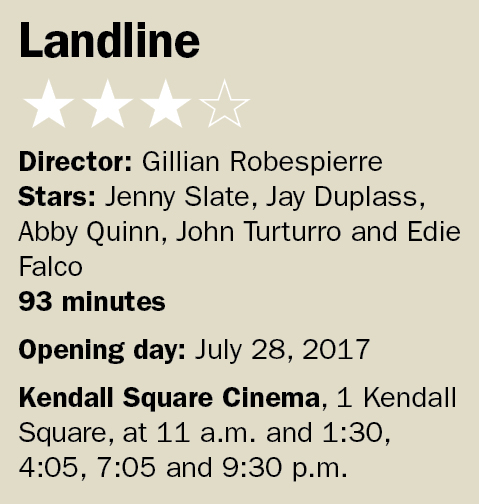

‘Landline’: When father’s fooling around, time to stop phoning it in about family ties

https://youtu.be/G58O0ub4XEM

The team-up of director Gillian Robespierre and actress and talk show guest extraordinaire Jenny Slate was the perfect coupling in their first feature together, 2014’s “Obvious Child.” Warm, hilarious, modern and romantic, the film showcased both at their versatile best. You always feel for a filmmaker who has an outstanding debut film and has to live up to it, especially when that work is so close to excellence as “Obvious Child,” but it’s difficult not to when it comes to “Landline” – a film that just scratches the surface of what “Obvious Child” accomplished seemingly effortlessly.

Set in the mid-1990s (hence the name’s reference to home phones) the film follows sisters Dana (Slate) and Ali (newcomer Abby Quinn, who is wonderful). There’s is a typical, fraught relationship in which one sister lives independently while the other, still a teen, mopes about at home and dabbles with hard drugs. Life chugs along with light bickering between family members until one night Ali discovers that her father (John Turturro) might be having an affair. Uncertain on how to bring it up to their hard-working mother (Edie Falco), the sisters keep the information to themselves and grow closer in the process, even when Dana’s own relationship with her partner (Jay Duplass) is put in jeopardy.

Set in the mid-1990s (hence the name’s reference to home phones) the film follows sisters Dana (Slate) and Ali (newcomer Abby Quinn, who is wonderful). There’s is a typical, fraught relationship in which one sister lives independently while the other, still a teen, mopes about at home and dabbles with hard drugs. Life chugs along with light bickering between family members until one night Ali discovers that her father (John Turturro) might be having an affair. Uncertain on how to bring it up to their hard-working mother (Edie Falco), the sisters keep the information to themselves and grow closer in the process, even when Dana’s own relationship with her partner (Jay Duplass) is put in jeopardy.

It’s a lot of plot to go through in just over 90 minutes, but the film nearly manages to give everyone a satisfying ending. In large part this is due to Robespierre’s keen understanding that her characters don’t need to be inherently likable to be empathetic. The disasters Dana finds herself in are largely of her own making, especially when infidelity is involved. Despite that, the film allows for her to be flawed without being demonized, a mess without being cartoonish and upset without wading into stereotypes of the “hysterical” woman. The film is much more interested in how Dana’s situation informs her relationship with her younger sister and how Ali, in return, is able to see Dana for the fallible and vulnerable human being she is, rather than just a nagging older sister.

The chemistry between Quinn and Slate feels genuine. They embody physically and emotionally what it means to be sisters, and the authenticity makes it both aggressively frustrating and wholly endearing to watch them squabble, laugh and share character-defining moments. It’s remarkably refreshing to see a director and creative team care so deeply about relationships between women – a dynamic cinema would benefit from exploring further, as “Landline” can only fill momentarily the void of films concerned primarily with relationships between women.

The film falters when it rushes, wrapping everything up in the last 20 minutes of the film. Seemingly determined to find a sense of a happy ending (while staying honest to their story) the film leaves us on a quiet moment of retrospection and celebration that feels tacked on. The script by Robespierre and Elisabeth Holm should have begun the redemptive arcs earlier in the film, rather than drawing out the reveals. Similarly, a subplot regarding Ali’s curiosity with drugs has the brakes slammed on. It’s a shame, too, since the character work done up until that moment is so beautifully depicted and fleshed out. The performances allow for characters who feel real in all their messiness.

Regardless, there’s something poignant about the film that allows it to linger. The creative team depicts womanhood, romantic intimacy and familial bonds with an acute sense of understanding and affection. From portraying casual, playful humor during sex, to the raw, stripped-away feeling of being the guilty party in a reconciling relationship, to the way siblings know how to aggravate you the most and make you laugh the hardest in equal measures, the film, above all else, feels emotionally sincere. The rough edges of “Landline” are apparent, but it’s a more than worthwhile picture and one that allows its protagonists to be simultaneously selfish but deserving of love.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks