Math tracks’ unintended consequences: Racial segregation into ‘the dumb class’

Manuel Fernandez, head of school at Cambridge Street Upper School, has charted a course on math unique from other Cambridge middle schools.

The district’s five middle school principals were visibly frustrated by the end of a School Committee roundtable about the middle school math program when Mayor E. Denise Simmons made it clear that there was no action in sight. This untelevised Nov. 14 roundtable – the first discussion with administration and committee members about the besieged program under Superintendent Kenneth Salim’s leadership – drew more than 25 teachers. Though the teachers were not invited to participate, the principals were, and they were united in opposing the dual track that they say has created, for the first time in the students’ school experiences, racially segregated classrooms.

“This system has produced significant unintended consequences,” said Amigos Principal Sarah Bartels Marrero of the 15-month-old structure that creates an “accelerated” and an “on-grade” track for seventh- and eighth-graders. She presented with principals Manuel Fernandez from Cambridge Street, Mirko Chardin of Putnam Avenue, Julie Craven of Rindge Avenue and Daniel Coplon-Newfield of Vassal Lane upper schools.

The accelerated classes are overwhelmingly white; the on-grade classes overwhelmingly nonwhite. At RAUC, for example, there are only two black students in one accelerated class, and only five white students in an on-grade classroom. The poor scores of students in the on-grade classes are “unacceptable,” Craven said.

“The current system has perpetuated a belief that black and brown students can’t perform well in math,” Bartels Marrero said. “It is a social justice issue. If we truly believe that all students can learn, then our institutions and curriculum need to represent that belief,” she said.

While Salim began the evening by saying there was no expectation of immediate final decisions, the apparent lack of urgency or interest in timely action by the School Committee was clearly disappointing to many middle school staff in the room.

Two-tier structure

At issue is the structure of teaching math to seventh- and eighth-graders that separates students into two leveled classes for the first time.

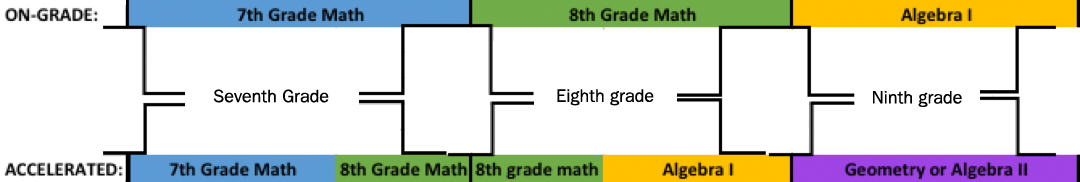

In the fall of 2015, under then-superintendent Jeff Young and with unanimous School Committee approval, the district created different streams for seventh- and eighth-grade math classes. The call for dual tracks came from many parents and students who complained “advanced” students were learning from computers in the back of the room or before school, or needed to take classes at the high school while still in middle school.

The students are sorted into the two tracks at the end of sixth grade by teachers. Accelerated students compress three years of math into two years, and if they pass the high school test, are ready to skip the standard ninth-grade math class. Last spring, slightly more than half of the students were in the accelerated class.

The principals said that the students refer to the two levels as the “smart class” and the “dumb class” and report hearing students in on-grade classes saying “it doesn’t matter what we do, they don’t expect us to do well anyway.”

“This doesn’t happen in other classes,” Craven said. “These comments start in seventh grade.”

“Middle school students are savvy,” Bartels Marrero said. “They know what pathway they are in.”

Unintended consequences

VLUS’ Coplon-Newfield detailed other problems created by the dual tracks:

![]() The racial split in the math classes is echoed in other courses, creating two distinct groups of students that end up traveling together all day.

The racial split in the math classes is echoed in other courses, creating two distinct groups of students that end up traveling together all day.

![]() Special education students are usually slotted in the on-grade level, which means these students are also grouped together for all of their classes.

Special education students are usually slotted in the on-grade level, which means these students are also grouped together for all of their classes.

![]() With an emphasis by the district and many parents to increase enrollment in the advanced track, schools need to create a third math classroom if the class size tops 25. This means the math specialist needs to teach the third class instead of providing intervention and small-group support to the whole school.

With an emphasis by the district and many parents to increase enrollment in the advanced track, schools need to create a third math classroom if the class size tops 25. This means the math specialist needs to teach the third class instead of providing intervention and small-group support to the whole school.

![]() Flexibility in scheduling teachers and students is severely limited. “We don’t have options when problems arise [with] two students who should not be together in the same classroom,” Coplon-Newfield said.

Flexibility in scheduling teachers and students is severely limited. “We don’t have options when problems arise [with] two students who should not be together in the same classroom,” Coplon-Newfield said.

![]() “If the goal is to create mathematicians who think out loud, we are limiting the voices in the classroom.”

“If the goal is to create mathematicians who think out loud, we are limiting the voices in the classroom.”

![]() Parents are stressed about getting their children into the higher track, even if it doesn’t serve the student well, and “if the parents have stress, that means the students are owning stress also,” Coplon-Newfield said.

Parents are stressed about getting their children into the higher track, even if it doesn’t serve the student well, and “if the parents have stress, that means the students are owning stress also,” Coplon-Newfield said.

![]() It seeps into the sixth-grade math class, where students and parents worry about getting into the accelerated track, the principals said.

It seeps into the sixth-grade math class, where students and parents worry about getting into the accelerated track, the principals said.

Disconcerting MCAS scores

Data on the math program’s results are elusive; the roundtable presentation included only state assessment data from last spring. That’s because the state began using the “MCAS 2.0” standardized test last year, which they say is more difficult and therefore not comparable to previous years. Administration did not present information on the Algebra I pass rate – that is, whether students covering Algebra I in the eighth grade were passing the test.

Those 2017 MCAS data, though, were not promising. In sixth grade, all Cambridge students and all subgroups – such as race-based or special education populations – outperformed the state average. By seventh grade, the portion of Cambridge students who “met or exceeded expectations” was about the same as the state average. Eighth-grade students scored below the state average. African-American/black student performance dropped significantly. The gaps between white, non-special education and non-poor students and everyone else grow from sixth grade through eighth grade.

Other moving parts include the implementation of a new million-dollar math curriculum called Math in Focus that began rolling out in 2013, and major revisions this year to the state middle school math standards increasing the rigor and pushing some topics taught previously in high school into the eighth-grade curriculum.

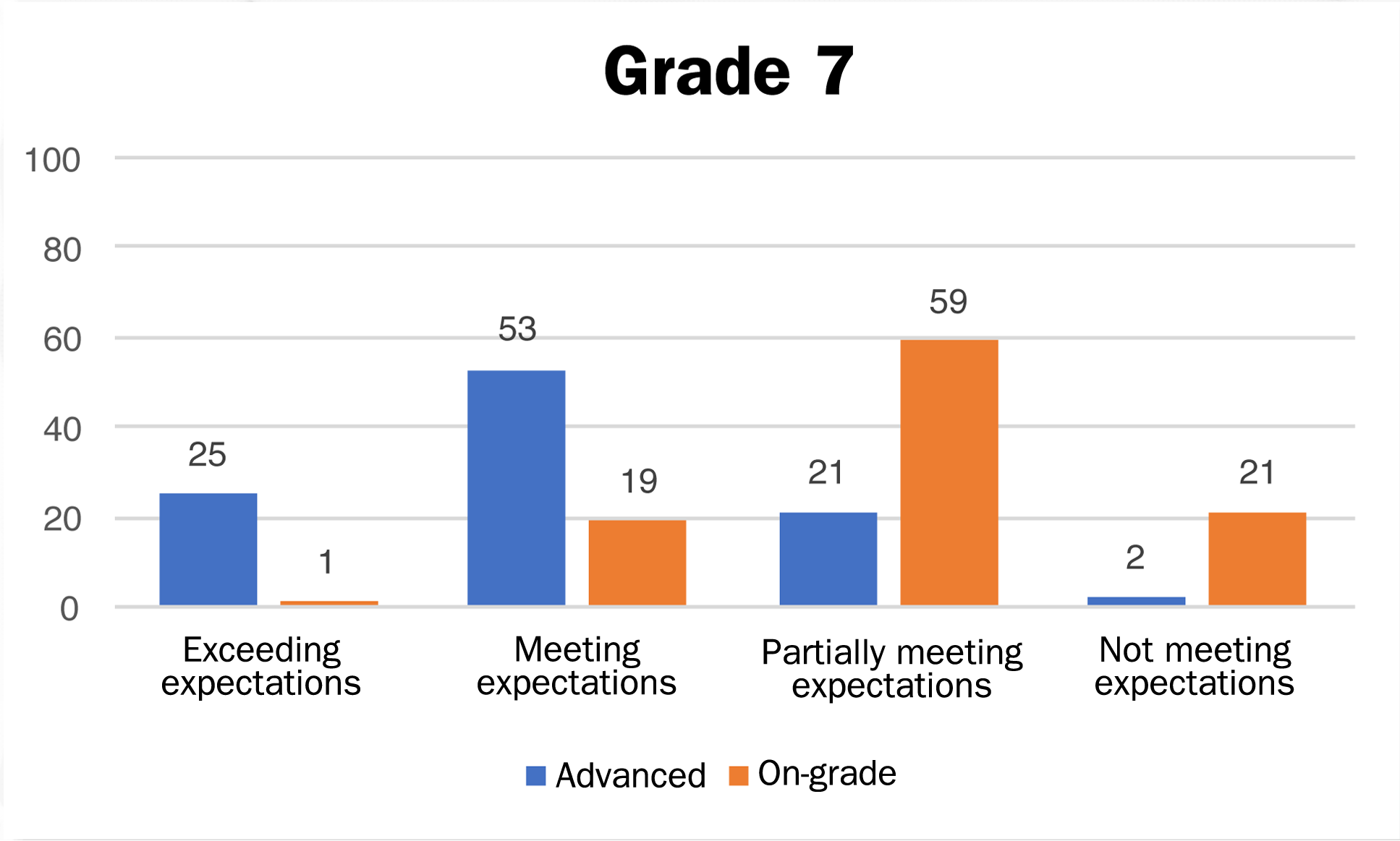

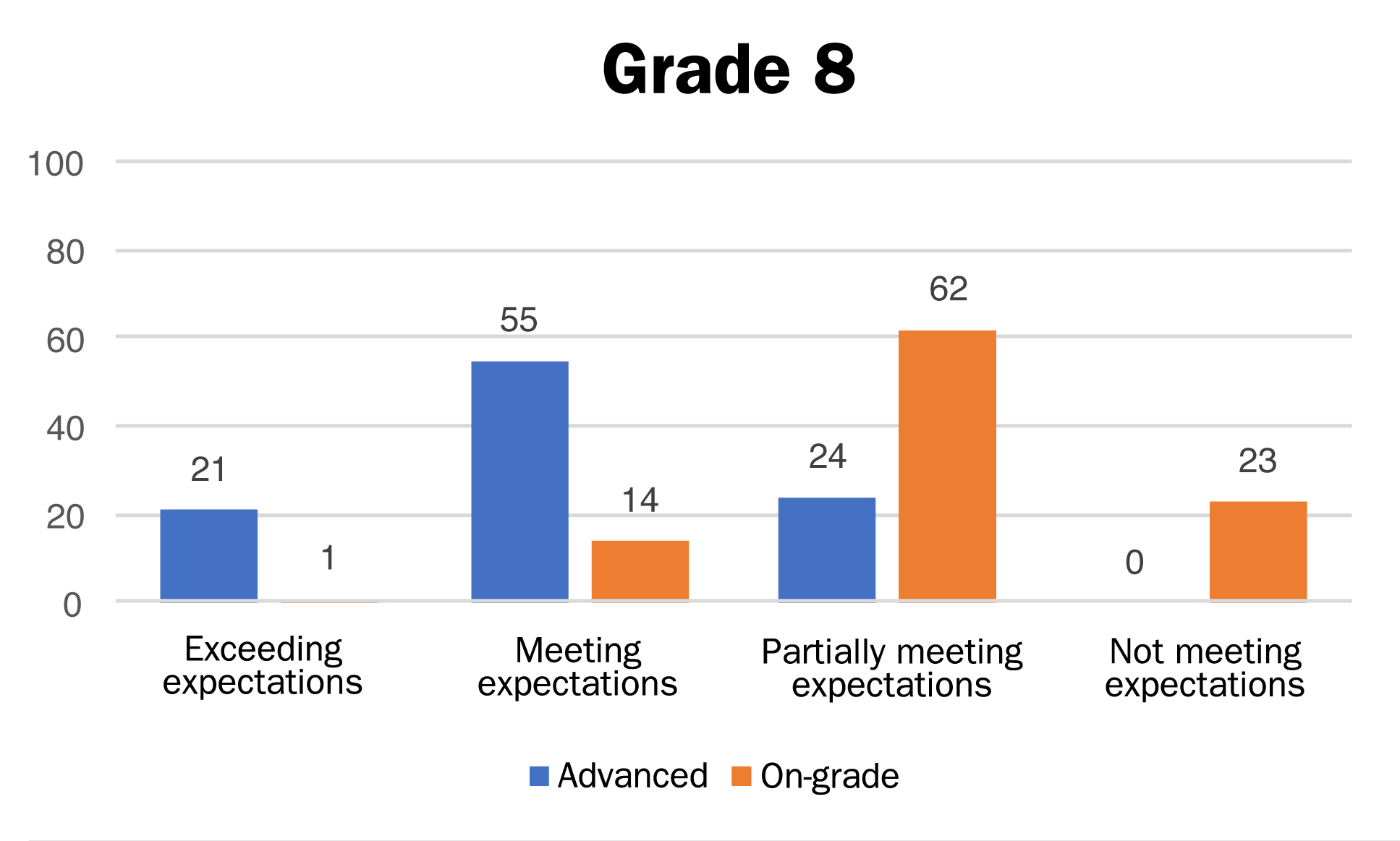

Data and graphic from Cambridge Public Schools’ “Upper School Math Program,” Nov. 14.

With these caveats, a review of seven years of data doesn’t show much change over the years. On average, about half of middle school students have scored as proficient or above (now renamed “meeting or exceeding expectations”) for the past decade, though they perform better in younger years.

Assistant Superintendent for Curriculum & Instruction Anda Adams and Julie Ward, the district’s new math coordinator for kindergarten through 12th grade – coming in after three years without a dedicated coordinator – presented data suggesting that only students in the advanced math classes seem to be meeting expectations for their grade level.

It is probably not surprising that students in the accelerated track score higher than the other group, if only because they are covering more material, but it is notable that the vast majority of the on-grade students are not meeting expectations for on-grade material, even though the curriculum has supposedly been realigned to match the new requirements.

Adams gave one other critical piece of information: The state measurement of how much individual student performance improves from one year to the next. Called “student growth,” Cambridge has an unusual result in the dual-track program: students in the accelerated class are showing more student growth than those in the on-grade class, which is the exact opposite of what other districts show. “If this pattern continues,” she said, “the [performance] gap between the two will get bigger.”

CSUS Pilot Program

Fernandez, of Cambridge Street, managed to win administration approval to pilot seventh-grade math this fall taught in heterogeneous classrooms – driven, he said, by his teachers wanting “to try something different, because what we are doing is not working.”

Fernandez said a group studied several models “at programs across the country, did some serious professional development”; redesigned the school’s schedule to allow for weekly math staff meetings; identified sixth-grade students for a summer math program to provide supports; and engaged families.

The key difference between Fernandez’s pilot and the heterogeneous classes that the parents and students protested in 2013 and 2014 is staffing: Instead of putting some kids on self-monitoring computer programs, the CSUS classes are staffed with interventionists and special education teachers who support the main math teacher, Fernandez said. It’s not unlike the co-teaching model in sixth-grade math that teachers have been asking to expand.

“We are already seeing students gleefully walk into classroom, excited and engaged. We see that with some of students now across the racial spectrum. We want to see it more,” Fernandez said.

Considerations

The emphasis on getting students through calculus by their senior year in high school – or at least the method – may warrant reconsideration, Adams suggested. There are two ways to finish calculus by 12th grade within the school system: compress middle school math to get through Algebra I in eighth grade, or compress high school math by “doubling up” – taking two years’ worth of math in one year, made possible by Cambridge Rindge and Latin School block scheduling that puts a year’s worth of class into one semester.

The state education department explicitly does not require calculus in high school for “college and career readiness,” the presentation highlighted, but does include calculus in an “acceleration option.” Adams’ presentation posed three considerations for the group:

![]() “Is our goal ‘enrollment in Algebra I in eighth grade’ or the ‘completion of college readiness’?”

“Is our goal ‘enrollment in Algebra I in eighth grade’ or the ‘completion of college readiness’?”

![]() “Acceleration at any time requires compacting the curriculum. That compaction looks different in middle school than high school.”

“Acceleration at any time requires compacting the curriculum. That compaction looks different in middle school than high school.”

![]() “Unintended consequences for students.”

“Unintended consequences for students.”

School Committee “response”

Few members addressed the first two considerations. Member Patty Nolan has long advocated Algebra I in eighth grade. While acknowledging the concerns expressed at the roundtable, Nolan worried that simply eliminating the dual track would not solve performance problems. “What we had before did not work either,” she said. Nolan, who was an advocate of the dual track in the 2014 decision, said that the move was born from teachers saying that “they could not teach across such a broad range” of skills.

Mayor E. Denise Simmons, chairing the Nov. 14 meeting, signaled she was not likely to move the committee to any decisions in the near future. “This is very complex,” she said, and warranted more meetings – likely an all-day Saturday meeting, she added, to an obvious lack of enthusiasm on the faces of many administrators and principals.

Simmons and committee member Richard Harding focused on the importance of engaging families when it came to slotting students into classes. “If I’m a parent not already in the engagement track,” Simmons said, “I’m going to miss that” there are concerns about on-grade classes. They extended this to the option of “doubling up” on math in high school – wondering how involved or aware parents were. It’s an important issue, but together the two spent a significant portion of comment time on it.

Simmons also fixated on the racial categories used by the state Department of Education when reporting data. Though the categories have been used for years by the state and the federal government – including in the U.S. Census – she and Harding were puzzled by the definitions of the “African-American/black” and “multi-race” categories. “What am I?” she asked.

“It’s self-reporting,” Ward explained. “It’s whatever you choose.”

“We should force our students to just pick one race box,” said a disconcerted Simmons, several times, even raising the issue in her closing comments as worthy of further discussion at that possible Saturday meeting.

Waiting on CSUS

While others expressed concerns, few suggestions for changes in math programs were offered. Harding suggested adding summer preparatory programs in earlier grades.

Member Manikka Bowman warned that there “needs to be a paradigm shift.”

“The way we have this conversation,” she said, “perpetuates the assumption that a black classroom is somehow lower-performing than other groups.” She said she wants the conversations to be “action-oriented” and fit into the district’s framework, but did not offer specific suggestions.

Vice chairman Fred Fantini seemed to favor waiting on results from the CSUS experiment. The other principals, though, they were not granted the option to try the Cambridge Street approach.

Summing up

Graham & Parks School staff member Rose Levine, who teaches all subjects to her fifth-grader, including math, was at the meeting. “It was clear to me, listening to the unanimous testimony from the upper school heads, that the system of tracking is damaging students, school communities and the quality of math education, and that it exacerbates and perpetuates racial and [socioeconomic] achievement gaps. Math education research tells us that tracking harms not only those students who are left behind, but the students labeled as ‘gifted’ or ‘accelerated’ too,” Levine said later.

“I was surprised that School Committee members weren’t quicker to denounce a system that is failing,” she said.

Coplon-Newfield seemed of the same mind during the meeting. “I’m not sure how much convincing I need to do,” he said, summing up. “We’ve been talking about this for over a year, and this flies in the face of the individual mission of the schools and of the district.”

This post was updated Nov. 22, 2017, to clarify information about race imbalance in classrooms at the Rindge Avenue Upper School.