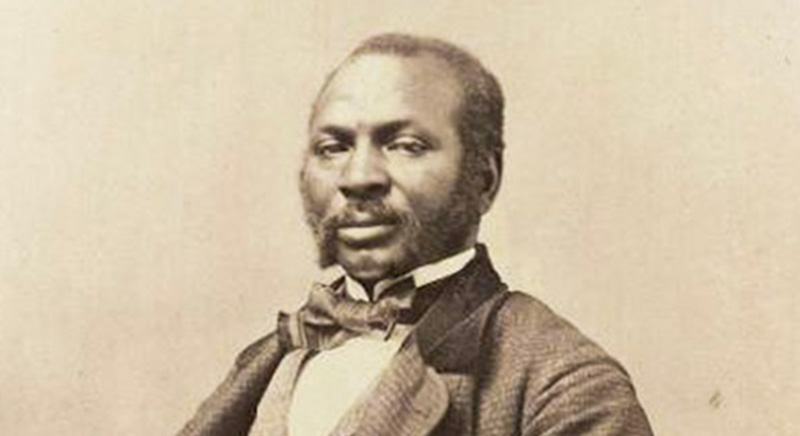

Francis Prince Clary was tireless in his advocacy, and even the music he performed was for equality

Francis Prince Clary’s signature: (Image: Massachusetts Archives)

We don’t know of any writing left behind by Francis Prince Clary – nothing to tell us his personal feelings about his participation in some of the most important political and moral struggles in this country’s history. But a list of petitions he signed and events he took part in give a good idea of his lifelong interests and zeal for justice. They also form a chronicle of advances and setbacks as Massachusetts Black and indigenous people tried to move the white population to honor the state constitution and its supposed Christian principles.

Petitions circulated around the state in 1843 asking the state Legislature to ban discrimination on the railroads. Clary was one of the first signers of the Boston petition; farther down the list are the signatures of his grandmother Beulah Bassett, mother Anna and sister Ann M. (Such laws did not pass for a decade.)

Clary was also one of the first signers in 1843 of a petition passed around during a Boston meeting of Black citizens, meaning he was probably one of the meeting’s organizers. The Massachusetts slave code had included an interracial marriage ban. In 1836, the Legislature reinforced the ban and explicitly made all the children of any such marriages illegitimate. This petition was part of a statewide campaign backed by Black and white Bay Staters to repeal the ban. It prevailed.

Clary and his brother George signed a petition in 1844 asking for the immediate end of segregated schools in Boston. (The city’s school committee rebuffed this and later petitions, sometimes offering explicitly racist justifications for segregation). He signed a petition to the state General Court the next year asking that “the word Color (as relating to human beings)” be erased from the voter lists and from all statutes. The community often split between those who believed segregated schools and organizations allowed them to escape white domination, at least for short periods, and those who believed segregation psychologically as well as physically enforced a color-based caste system and delayed or flat-out prevented eventual political and social equality. Clary was an integrationist, even to the point of signing a letter to the people of Cambridge in 1865 asking them not to contribute toward the establishment of a Black church in the city. The letter said it would “distract the union among us” and reverse social and political progress. (Given the religious, social and political importance Black churches have played in U.S. history and today, this may seem a strange stance. But it was not rare at the time among Black activists.)

Through the 1850s, Clary joined with other area Black activists asking why they, citizens born in the United States, were barred from military service but recent immigrants were not. In 1851, he signed a petition asking the state government to recognize the Boston Massasoit Guards, an independent militia that seems to have been formed by Black men after the Fugitive Slave Act to fight slave catchers; the petition was denied. The fight continued, and Clary’s name is on an 1857 petition asking the state to charter a Black military unit. Not until the Union needed more troops did the government approve formation of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment in 1863.

A grand sacred vocal concert program in which Clary sang and played instruments (Image: The Liberator of Jan. 5, 1844)

Clary’s music was also activist. In addition to playing in concerts – some aimed at his community’s elevation, some in celebration of anti-slavery milestones, and some to raise funds for civil rights efforts – he also led the well-known Clary’s Cornet Band. His band can be found in accounts of commemorative parades in Cambridge, Boston and New Bedford and likely played in other cities as well.

Private houses and functions hired Clary to play at parties and other events. (Image: Cambridge Chronicle of Dec. 3, 1853)

These decades also sent domestic joys and sorrows to Clary and his wife, Maria Lewis Clary. Her father and uncles worked at Harvard, first as “scouts” cleaning students’ rooms and blacking their boots, and later as janitors. Her uncle, Enoch Lewis, had been superintendent of rooms for decades. Clary joined them some time in the 1840s.

In 1850, Clary bought a house and land at 49 Dunster St. from Thaddeus William Harris, then librarian of Harvard. (It’s not clear Clary ever lived there, or for how long he owned it. By 1868, the property was owned by Harris’ estate, and the 1850 sale may have been a financial transaction of convenience between the two men.) In 1851, Clary bought a house and land from builder and land speculator Oliver Hastings on today’s Roberts Road, then known as Tremont Street but soon renamed Baldwin Street. He and his family would live here for the rest of his life. When he bought the property, it must have seemed idyllic. Although it was a short walk from Harvard, there were few other houses on the street and the property backed onto acres of verdant nursery owned by Charles and Phineas Hovey.

Daughter Emily was born in 1852 and Addie Maria in 1854. But also in 1854, 5-year-old Herbert died of scarlet fever. In 1856, Charles was born and died a month later of “cholera infantum.” Over the course of 1856 and 1857, two of Francis’ sisters and his mother died. Hannah Lizzie was born in 1858 and Lucy in 1860.

In 1858, Maria’s uncle Enoch Lewis led a group including many family members to Liberia; he was most likely despairing after the previous year’s Dred Scott decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which included a ruling that people of African descent could never be U.S. citizens. Within months, Enoch, his wife, and other members of the party were dead of “fever.” Others returned to Cambridge, some dying soon after.

In 1860, 6-year-old Addie died of “lung complaint.” In 1861, one-year-old Lucy died. This number of family deaths was not unusual in Black or white families at the time, but as devastating as they would be to the parents and siblings, they would also have hit hard in the wider Cambridge Black community, most of whose members were related to each other or worked together.

This decade, the 1850s, also saw a number of violent political, legal and physical struggles in Boston as the Black community and white allies struggled to protect and save fugitive slaves from other states. It’s not known whether Clary was involved directly in these efforts, but people he knew well were. The Fugitive Slave Act and Dred Scott decision especially made even free Black people with deep New England roots, such as the Clarys, fear that any worth they had proven or security they had built might imminently be ripped away.

At work at Harvard, though, Clary found an interesting new opportunity.

![]()

About the Cambridge Black History Project

The Cambridge Black History Project is an all-volunteer organization of individuals having deep roots in Cambridge. We are committed to researching, accurately documenting, preserving and illuminating the journeys, accomplishments and challenges of Black Cantabrigians, and to raising awareness of their stories through educational outreach to the Cambridge community and beyond.

The Cambridge Black History Project is an all-volunteer organization of individuals having deep roots in Cambridge. We are committed to researching, accurately documenting, preserving and illuminating the journeys, accomplishments and challenges of Black Cantabrigians, and to raising awareness of their stories through educational outreach to the Cambridge community and beyond.

Special thanks for research help to Charles Sullivan and the staff at the Cambridge Historical Commission and Alyssa Pacy at the Cambridge Public Library Cambridge Room.