Zinc buildings shuts off its trademark LEDs amid glare of Outdoor Lighting Task Force

The Zinc apartment building in East Cambridge has been told to shut off its roofline LEDs. (Photo: Marie Saccoccio)

When the lights came to life atop the Zinc luxury apartment building in East Cambridge, so did the neighbors.

City officials heard a flurry of complaints about the three wide stripes of oscillating color LEDs across the roofline of the 15-story, 392-apartment building near Charlestown and Somerville.

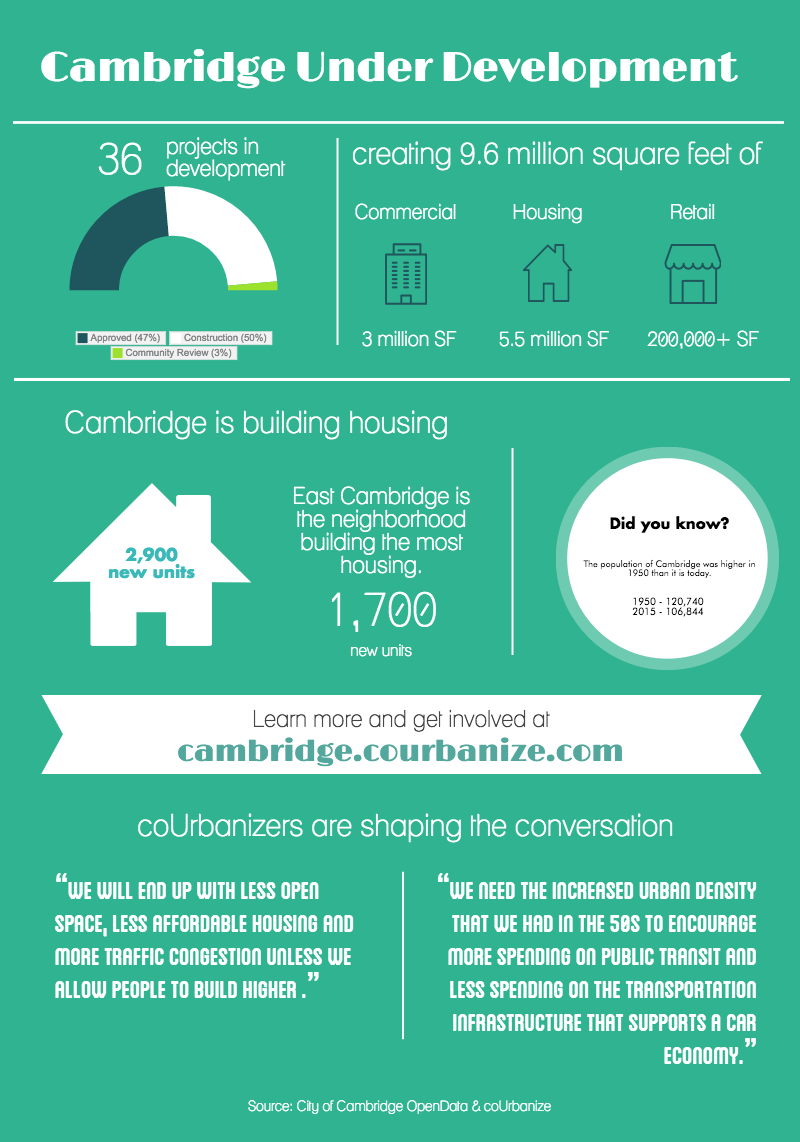

And Zinc is just one of many projects contributing to a brighter city. CoUrbanize, an online facilitator of development discussions, says Cambridge has 9.6 million square feet in development among 36 projects, half of which are already in construction. Nearly 60 percent of the residential units coming along are, like Zinc, in East Cambridge, which is also taking spillover from Kendall Square innovation industries. The 220,000-square-foot Davenport building on First Street, once a furniture factory, now rents to high-tech industries active at night.

“It just came to a head here in East Cambridge because suddenly we have buildings illuminated all night,” resident Marie Saccoccio said, citing both buildings as adding to her alarm.

Long in the works

That brings renewed interest and urgency to the work of the city’s Outdoor Lighting Ordinance Task Force, which has met 13 times over three years and is near filing a draft for city officials to examine, said Lisa Hemmerle, director of economic development at the Community Development Department and recently leader of the task force. The hope is for a draft to reach the City Council in March.

The task force began meeting in 2013, after a City Council vote fell short of approving a light ordinance change proposed by citizen Charles Teague, although complaints about light leaking into windows citywide despite an existing, unenforced glare ordinance went back several more years. Teague, who tried to get his zoning through three times in two years, joined the task force, where he continues to worry that a development-friendly approach is combining with efforts by businesses to brand themselves to stand out.

“It’s turning Cambridge into Little Tokyo,” Teague said, but when renters and homeowners decide on a neighborhood, “they don’t expect people to put on a light show all night.”

Permitted? Zinc again

Zinc’s roofline outdoor lighting has been shut off for much of the week and will stay off, the task force was told at its Thursday meeting. But the reason is something of a fluke.

Developer Wood Partners checked with the city last year to see if it could have the lights – and were told yes, leading to a design and installation reportedly costing up to $50,000. (Wood Partners, which inherited the special permit for Zinc at 22 Water St. from an earlier developer, didn’t make a representative available to be quoted for this story.)

“I verified [with Community Development] that since there are no conditions, fine,” said Ranjit Singanayagam, head of Cambridge’s Inspectional Services Department. “But recently we found that even though there are no conditions, the previous owner had said on its application it wouldn’t have any lights on the penthouse.”

Similarly, a complaint was heard Thursday about the new Martin Luther King Jr. School at 100 Putnam Ave., which a neighbor has described as “ablaze until 10 o’clock at night” with no shielding, invading the otherwise residential street with glare starting at 5 a.m. daily. But by Friday afternoon, city officials were reporting that they’d looked into the situation and had solutions on the way, including a screen panel to reduce light coming from an interior stairwell.

Inside job

With its work wrapping up, members are seeing the tasks force’s strengths and weaknesses, with a widely acknowledged primary weakness being built into its mission: The task force cannot make or enforce rules concerning light that comes from inside a building, and that means there are no rules about unshaded windows lit through the night, even in glass-front buildings or open-air structures such as parking garages.

“Those are inside the building envelope, and anything inside the building envelope is considered interior lighting under building code, and we’re not looking at that,” Hemmerle said. “We’ve recommended to the task force and the task force might recommend to the city manager and City Council that another group be formed to look at interior lighting, because we have heard that concern and understand that concern. ”

The ordinance the task force is crafting sets two standards, she said. One is a “prescriptive” checklist made to be easy to follow for smaller projects, such as home construction, and the other is a “performance” standard where large projects aim for goals in the green building certification program known as LEED. Even a “net zero” building such as the King School can be powerfully lit, though, and there are loopholes to ironed out. On Thursday, Teague and task force lighting consultant Jeffery Berg looked at a proposed rule saying there was no limit on how bright facade and landscape lighting could be, so long as it was off from midnight to 6 a.m. daily.

Task force concerns

In a call before the Thursday meeting, Hemmerle addressed some of the concerns being raised by task force members and residents such as Saccoccio.

Light trespass across zones. “The zoning on my block is irrelevant, because right across the street is zoning that’s far more permissive. They need to remedy the fact there’s all this spillage from commercial and business areas into residential areas,” Saccoccio said. It’s an important issue, agreed Carol Lynn Alpert, a resident representative on the task force who saw no accommodation in the language of the ordinance for people on the boundaries of commercial and residential lighting zones.

Hemmerle, though, said residents “will still have relief”:

“Because if [businesses are] not meeting a prescriptive standard in a residential zone, they still have to meet the performance standard in a more commercial zone. And both standards are quite similar when it comes down to lumen levels and light trespass levels. In some cases, the performance standards are actually more restrictive. You still won’t be allowed to have light trespass between light shining off your property onto somebody else’s property, you will not be able to have lumen levels above a certain limit. It’ll eliminate so many of the issues we don’t have limits for in the current zoning.”

Enforcement. While Alpert acknowledged “a concern that there be teeth in the ordinance” and wondered whether Inspectional Services would have the staff, equipment, funding and overall ability to enforce the ordinance, Teague was even more skeptical. A large property owner that met city standards when opening its doors might slip out of compliance over time, and “there are no inspections, and they don’t have the right to go your property,” Teague said. “At its core, a huge percentage of this is unenforceable.”

Hemmerle stressed that enforcement is driven by complaints, and that city inspectors can go on the property of a complainant to see how they’re affected by someone else’s light use – and onto the property causing complaint, if invited.

“But you don’t need to be on that person’s property to see light trespass. Inspectors can use a lux meter and they don’t have to be on the person’s property to determine whether there’s a violation. [Working at night] is a recommendation that the task force may consider including in their memo to the city manager and City Council. It’s not something you can put in a municipal ordinance. You also can’t include staffing levels – however, that can be a recommendation.”

Grandfathering. Saccoccio worried that the ordinance, which still has months to go until submittal and faces more months of council review and a potential second draft, won’t be in place soon enough to help East Cambridge. “It took them three or four years to come up with this, so a lot of buildings here will be in compliance and grandfathered in,” she said. Alpert thought the arrival of new light technologies, which use less energy for brighter results, would bring an onrush of buildings against which the ordinance was helpless – glassy towers lit from within with gaudily illuminated tops for branding. “Zinc is very interesting because it’s a good example of what happens the longer we delay. The longer this takes, the more these projects can come in and get approved,” Alpert said. “So we’re sort of under pressure to get approval as soon as possible, which may mean we have to compromise on what the ordinance can be.”

But Hemmerle said larger projects such as Zinc don’t apply at all, because they have special permits “that are very specific about what they can and can’t do. And if they’re not allowed under their special permit to do this type of lighting, then they can’t. They would basically be asked by ISD to turn it off. There’s no really getting ahead of the ordinance.”

For everyone else, she said, there is no grandfathering in the law – everyone has five years to come into compliance, and interim modifications are to be made immediately where possible to “replace that light bulb or maybe direct the light down so it’s not shining directly into somebody’s house, so we’re giving immediate relief to people where it’s possible.”

“For a resident, say somebody who went and spent a lot of money on their light fixtures, that’s the kind of person we’d want to protect – so long as it’s not a nuisance to their neighbors. We’d want to give them some time to comply without costing a fortune. The five-year period is as much to protect the residents as anybody else, so we’re not causing people to rip out light fixtures and throw them away, which is not good for the environment.”

No right to sue. Concerns about “administrative exemptions” being granted that basically allow the ordinance to be ignored are overblown, Hemmerle said:

“People can ask for an administrative exemption, but it has to obviously be a significant reason – like their income level doesn’t allow them to meet the standard of the ordinance. Or a person is disabled and needs their light fixture to be a different height or lumen limit, because maybe they have a vision impairment and need a brighter bulb. I can’t see that there would be any reason a larger project would get an administrative exemption.”