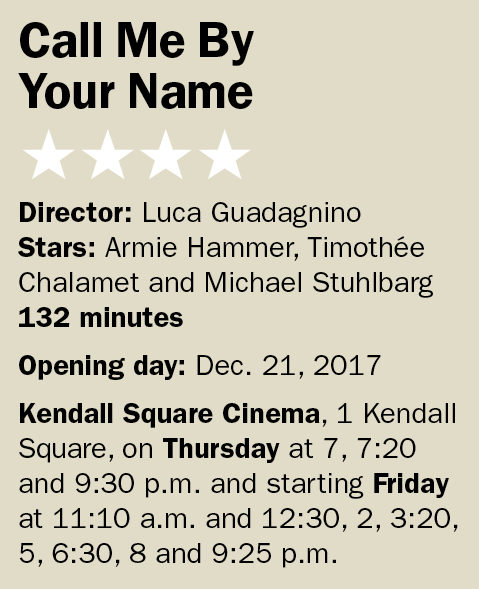

‘Call Me By Your Name’: It’s summer love that’s as beautiful as a family villa in Italy

So infrequently does a film as purposefully languid as this arouse such urgency in its audience. “Call Me By Your Name,” directed by Luca Guadagnino, asks viewers to allow themselves to become pliant and transported to a place and time not so far removed from our now, nudging us to yearn for love so tender and all-encompassing that it’s destined to break your heart.

The year is 1983, and the summer is well underway for 17-year-old Elio (Timothée Chalamet), something of a musical prodigy who lives with loving parents at their 17th century villa in Lombardy, Italy. His days are spent wandering the town, sparking a flirtation with a local girl, playing and composing music and reading. This all changers when his father, Mr. Perlman (Michael Stuhlbarg) invites his latest grad student, Oliver (Armie Hammer), to stay with them for six weeks. Initially annoyed with one another, then contemptuously fascinated, the two spark a passionate love affair as Elio continues to come into his own.

The year is 1983, and the summer is well underway for 17-year-old Elio (Timothée Chalamet), something of a musical prodigy who lives with loving parents at their 17th century villa in Lombardy, Italy. His days are spent wandering the town, sparking a flirtation with a local girl, playing and composing music and reading. This all changers when his father, Mr. Perlman (Michael Stuhlbarg) invites his latest grad student, Oliver (Armie Hammer), to stay with them for six weeks. Initially annoyed with one another, then contemptuously fascinated, the two spark a passionate love affair as Elio continues to come into his own.

Guadagnino has an eye for fashionable, meticulous compositions but brings enough warmth to the screen to avoid looking like a magazine layout. The greens of the trees that engulf the villa burst, the lines of the characters’ bodies are captured expertly to showcase an easy titillation that thrums through the film, and the architecture of the household is both foreign and inviting. The frames capture an impatient sensuality, clawing both at Elio’s chest and the sun-baked corners of the screen. Chalamet walks in circles around Hammer, leans into him with abandon, nips at his shoulder before pacing away, unable to focus his attention, but the film is also patient as the two ride bikes through a field, content in watching them pass by the camera and into the distance. Cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom is the perfect partner to Guadagnino, who captures the romance of the story with a quiet confidence.

Chalamet is a revelation, stunning with a superb performance that’s being named by many (this critic included) as the best of the year. He’s achingly real, presenting such authenticity in his awkwardness, naked want and devastation that it’s painful to watch. With Chalamet it’s the little moments to look for; he never makes the mistake of going big with emotions when a subtle blinking away of tears will do. It’s profound work, and he’s the pounding heart of the film. We find ourselves engrossed in our want for his ultimate happiness, something the film teases us with constantly. The work is nuanced, the way he leans in for affection, shutting down when he feels insecure and opening up once his flirtations are reciprocated.

Hammer is equally fantastic as Oliver – statuesque and startlingly handsome, he’s doing his best work since his breakout in 2010’s “The Social Network.” While Elio is more inexperienced and flustered, Hammer finds the right note of vulnerability to play so we’re never led to believe the story is one sided. We may spend our time in Elio’s head, but Oliver’s longing is just as tangible.

The chemistry of the leads extends to the rest of the cast. Stuhlbarg and Amira Casar do tremendous work as Mr. and Mrs. Perlman. Stuhlbarg (having a banner year, considering he’s also in “The Shape of Water”) nearly runs away with the end of the film with a scene so full of affirmation, compassion and empathy that it could have been seen as too good to be true, especially set in the early 1980s. Stuhlbarg delivers it with just the right amount of tenderness, though, giving his grieving son a lifeline that’s comforting but honest.

Written by master scribe James Ivory and based on the novel by André Aciman, “Call Me By Your Name” is languorous work, a special film that takes its time sinking its teeth into us, so subtle in its advances that we don’t realize how far gone we are until it’s too late. It’s astonishing just how explosively visceral the emotions of Elio and Oliver are, as they’re packaged in such a soulful manner. So much of the weight of the picture hangs on what isn’t said, a silence shared between the two made up for with physical proximity. Ivory proves vital, because he’s able to write into the pages the substance in the silence, and the performers follow.

As Sufjan Stevens sings over the end credits we’re struck by how powerful the journey has been, and how much has transpired in what feels too short a moment – just as Elio must feel. We are putty in the filmmakers’ hands, attached to the lives of these two strangers and transfixed by their impassioned love story. “I have touched you for the last time/Is it a video” Stevens sings and, in a later verse, “I have loved you for the last time.” It’s a striking reminder of the power of memory and the idea that love lost isn’t love wasted, a message that rings beautifully clear and universal no matter how singular and lasting the story of Elio and Oliver is.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks