‘The Hate U Give’: She’s no ‘angry black girl,’ until a fatally violent world forces the matter

Evocative, raw and embracing the leading lady’s mounting, righteous rage, “The Hate U Give” delivers a well-formed and simmering argument in favor of telling stories built on a foundation of anger. While the film possesses a great deal of compassion, humor and warmth, it’s response to injustice that makes for one of the most startlingly visceral films of the year.

Starr Carter (Amandla Stenberg, delivering her best performance to date) exists in two worlds. The first is her home life in the predominantly black neighborhood of Garden Heights, where her father owns a shop. After witnessing too many tragedies, her parents decided to send her to Williamson, a largely white private school where appropriation is the norm and Starr worries she’ll be labeled as the “angry black girl” if she doesn’t stomach her white peers and boyfriend Chris (K.J. Apa) tossing around black slang. Her life is coded by unspoken rules and expectations, something that’s violently disrupted when one night on a drive home, she and childhood friend Khalil (Algee Smith) are pulled over by a cop and he’s shot, left to bleed out in front of her as her screams for help go purposefully unheard by the assailant. This launches a campaign we’ve all become too familiar with, as the black community rallies and Starr is thrust into unsought limelight when a local activist (Issa Rae, of “Insecure”) calls on her. It’s made all the more complicated by the involvement of local gangster King (Anthony Mackie), who believes Starr’s testimony may incriminate him, since Khalil had been forced to work for him.

Starr Carter (Amandla Stenberg, delivering her best performance to date) exists in two worlds. The first is her home life in the predominantly black neighborhood of Garden Heights, where her father owns a shop. After witnessing too many tragedies, her parents decided to send her to Williamson, a largely white private school where appropriation is the norm and Starr worries she’ll be labeled as the “angry black girl” if she doesn’t stomach her white peers and boyfriend Chris (K.J. Apa) tossing around black slang. Her life is coded by unspoken rules and expectations, something that’s violently disrupted when one night on a drive home, she and childhood friend Khalil (Algee Smith) are pulled over by a cop and he’s shot, left to bleed out in front of her as her screams for help go purposefully unheard by the assailant. This launches a campaign we’ve all become too familiar with, as the black community rallies and Starr is thrust into unsought limelight when a local activist (Issa Rae, of “Insecure”) calls on her. It’s made all the more complicated by the involvement of local gangster King (Anthony Mackie), who believes Starr’s testimony may incriminate him, since Khalil had been forced to work for him.

The anxiety begins mounting at the film’s start, when Starr and her half-brother are sat down at the table by their father to hear how to handle being pulled over by a cop: Never seem belligerent, never hint at a threat that isn’t there – because that is how he’s seen young black men and women be targeted, even if they’re doing something as innocuous as holding a hairbrush (or toy, or bag of candy) like Starr’s doomed friend. Moving on to the Black Panthers’ Ten Point Program, he wants his children to understand how the world sees them but know they should have immense pride in being black.

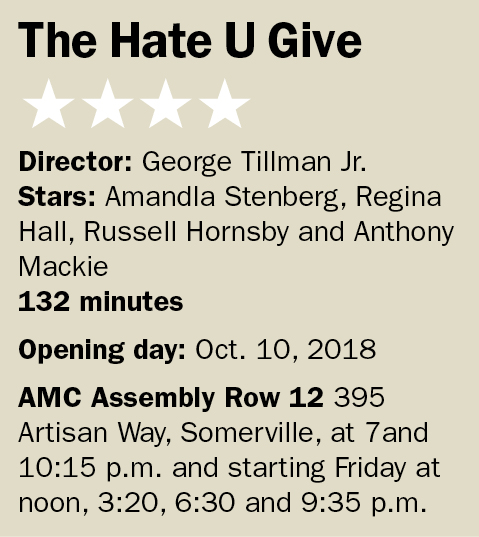

Audrey Wells (the director of “Under the Tuscan Sun,” who sadly just passed away) adapted from Angie Thomas’ wildly popular 2017 young adult novel of the same name, and she and director George Tillman Jr. do well in bringing it to life, delivering a potent message of victims waging war against injustice borne of others’ hatred, forced to deal with the outcome of irrational fear and destructive prejudice. It leans heavily toward delivering teachable moments to its target audience (and with the progressive, forward movement teens are burdened with leading these days, why not?) but never comes across as cloying or insincere. The moments of loss aren’t manipulative, but immediate.

Stenberg, best known for her role as Rue from “The Hunger Games,” comes into her own here with an impassioned stance and fluid physicality – watch her hunch in the moment she watches her friend die, turning inward from the world as she braces for impact. It’s a confident turn, matched by every performer in the film – from Smith’s memorable performance, making his loss all the more painful, to Regina Hall, playing Starr’s mom.

It’s Russell Hornsby as Starr’s father who is the standout, and who should be making everyone’s Supporting Actor list as we inch closer to Oscar season. Hornsby is empowered but never overpowering, offering a languid confidence in scenes as opposed to nerve-rattling defiance in others. He’s a force to be reckoned with, the building block that Starr and her brothers have built their belief systems off of, vulnerable and open in his mistakes but so fully the protector of his unit and ready to give all to defend them.

Every moment of relief or love is that much more powerful because of the built-up tension, and Tillman and Wells, regardless of the serious subject, never forget moments of levity or, most importantly, optimism – because what is a fight for justice without the hope it all might be worth it for a greater outcome? “The Hate U Give” heralds a generation of kids who lived and breathed by Harry Potter and the wish for magic to invade their lives, who have grown up with fingers attached to keyboards, who have watched peers die at rates too enormous to quantify, and offers them a rallying, righteous call to arms that tells them it’s okay to be angry, to feel defeated and to mourn, but also to stand up and make sure their voice is heard.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks