Election Commission delays city-line decision

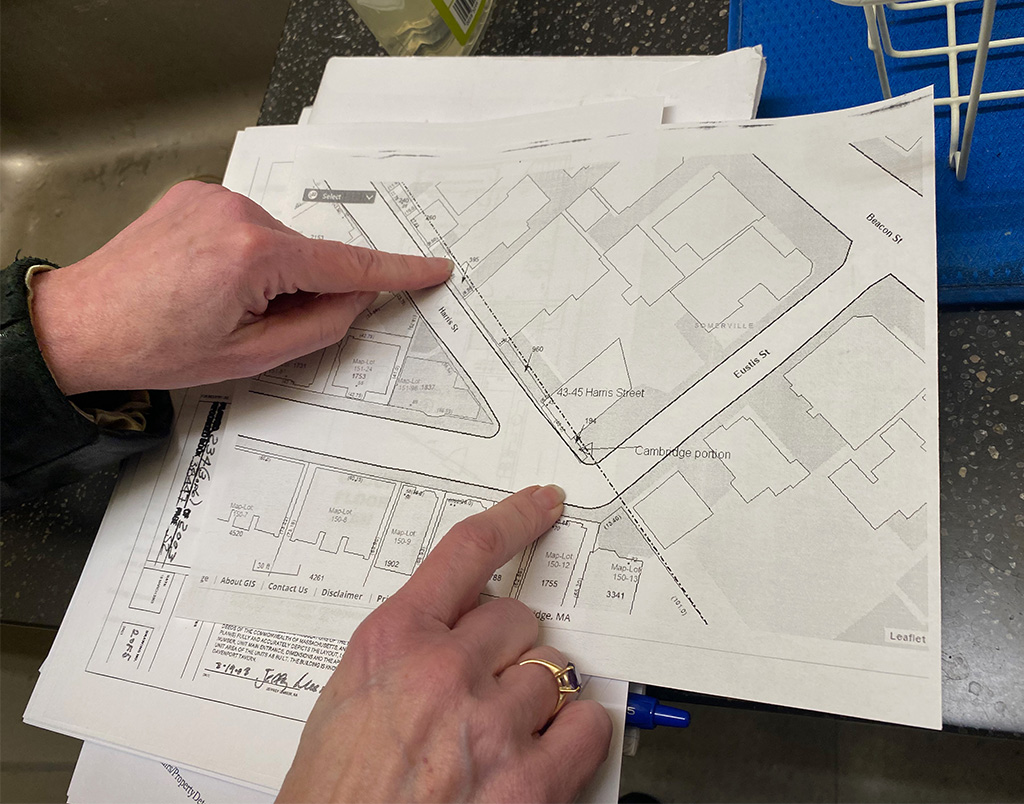

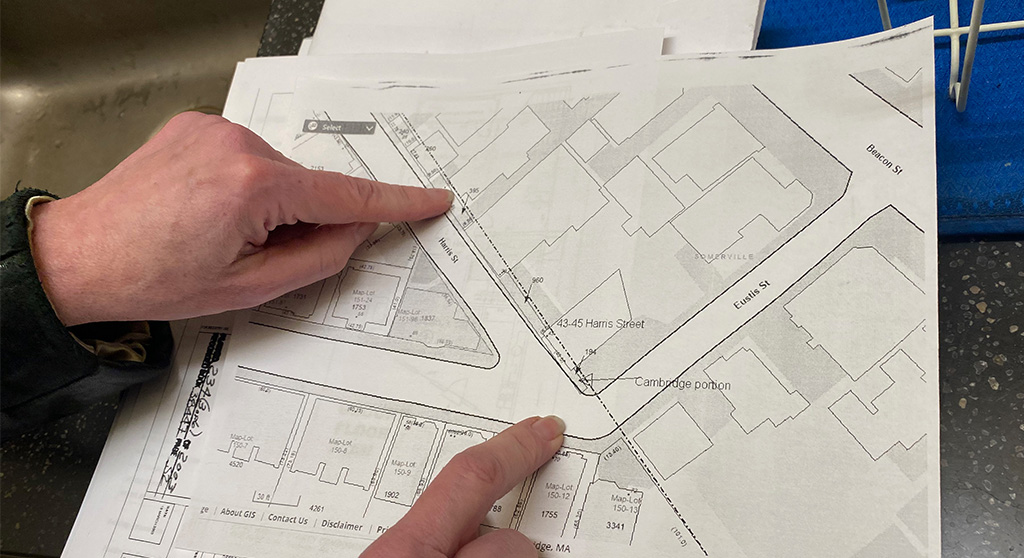

Heather Hoffman points out the city line on a plan examined by the Cambridge Election Commission on Feb. 15. (Photo: Marc Levy)

Faced last month with deciding if the resident of a house divided by the Cambridge-Somerville city line was properly voting in Cambridge, the Cambridge Election Commission decided to delay a vote, “get more information and come back in a couple of weeks.”

On Wednesday, armed with a memo from the Law Department, research from their own staff and more information presented during presentations, commissioners decided to delay a vote, get more information and come back in a couple of weeks.

Or four weeks.

Or more.

“This doesn’t feel right,” commissioner Ethridge King said.

“I can’t make this decision lightly,” commissioner Larry Ward said.

Law Department and city engineer

On its face, the case is fairly simple: Political activist Charles Teague spotted the name of urban-planning consultant and former Cambridge city councillor Sam Seidel as one of 10 names on a zoning petition for a small parcel in North Cambridge that put that petition in front of Cambridge’s Planning Board and the City Council’s Ordinance Committee – a right limited to residents. Teague didn’t think Seidel, whose mailing address is on Harris Street in Cambridge, lived in Cambridge: The city line cuts across Seidel’s porch. So although 193 feet of the property where Seidel lives is in Cambridge, Seidel lives in a house in Somerville that, until 2003, had a Somerville address. It has been assessed for taxes in Somerville since the 2010 fiscal year, it was established during the meeting, and he pays his taxes there, though most of his services are provided by Cambridge.

In such cases, “the Elections Division of the Massachusetts Secretary of State Office advises that, for voting purposes, a person resides in the municipality ‘which contains that part of the home where he or she habitually sleeps or which is most closely connected with the primary purpose of a dwelling,’” wrote city solicitor Nancy Glowa in a Wednesday decision asked for by election commissioners.

A survey from new city engineer Jim Wilcox confirmed that zero percent of the building in which Seidel says he sleeps is in Cambridge, Election Commission chair Charles Marquardt said.

“It’s pretty clear-cut,” Marquardt said.

“We could have a problem on our hands”

But when Marquardt made a motion to find Seidel incorrectly registered as a Cambridge voter and remove him from the rolls, he got no second from King and Ward, the other commissioners in the meeting. They expressed concern about nine other properties on the street where a decision applied to Seidel could have an effect – which commissioners agreed they would have to take up next.

“We’re not trying to kick the can down the road. I mean, I can make a decision on this. But I want to make the right decision. And I want to make the decision in the best interests of all enrolled people,” King said, demanding there be “a plan” before he votes. “Because we can sit here and make a decision on one person and then it snowballs and we could have a problem on our hands.”

“Have an avalanche on your hands,” Ward said.

Address doesn’t change

It wasn’t clear what they were talking about.

In the map provided by the Department of Public Works showing Harris Street “sliver parcels” a check with the Somerville Election Commission shows most vote in Somerville, said Heather Hoffman, a lawyer representing Teague.

A resident who identified herself as having a Cambridge address urged them to “hit the pause button and think about the ramifications,” expressing concerns about a child being turned away from Cambridge Public Schools because to register there, a family must show mail with a Cambridge address. It went by without comment that this would not be a problem. It wouldn’t even be a problem for Seidel, if he had children, as his Cambridge address was not in question and would not change.

King also worried that Seidel would have a problem getting mail – again, his address would not change – or registering to vote with Somerville.

Going backward

Concern about this kind of city-line issue affecting voters with homes crossing into Arlington and Belmont was raised as another reason to pause.

This being a responsibility of the Election Commission, assistant director of the commission Lesley Waxman told King and Ward that a lot of those line-straddling properties had already been handled, just as King, Ward and Marquardt were being asked to do with Seidel.

Oddly, King interpreted this as Waxman saying that “if we address this one … we have to go backward to the others.” Ward said the Seidel case “sets a precedent.”

Both comments seemed to ignore their staff’s explanation that the commission already had precedent from its own past actions, as well as from Glowa’s memo citing state case law going back 184 years to 1839.

“The opinion of the solicitor is not etched in stone,” King said, suggesting the commission could apply an alternative standard.

No next date set

Marquardt reminded his fellow commissioners that “we cannot make our own law.”

“We’re tasked with one thing – determining where people should be registered to vote. It’s a bad situation, but that can’t just be why we don’t follow the law,” Marquardt said.

But they could delay acting on the law, and citing the need to get more questions answered and with a complaint that Glowa’s three-paragraph memo had arrived “just that evening,” commissioners decided to recess their hearing to a future date. Marquardt proposed March 15, unless more time was needed by the Law Department to handle the growing number of questions.

King suggested a four-week delay instead, and Ward replied that he too worried there would not be “enough time.”

It wasn’t just public officials suggesting that the law was overrated. During a brief public comment period, Robert Winters, who maintains a site that follows mainly local politics, suggested that people who live in homes divided by city lines could “simply make a declaration” about where they live and would “have to stick with it.” Hoffman, a lawyer who practices in real estate, said that would be a fine rule if there weren’t already state law on the matter and nearly 200 years of case law underpinning its use.

Here is my suggested compromise: These people now live in Somerville, but Mr. Teague has to leave too for clearly being a rather unpleasant neighbor.

If being an unpleasant neighbor required people to leave we would have no housing shortage. :)

See! Stone… birds… you know the drill

how about following the law instead of friends on the commission?