MIT needs 1,000 grad student beds amid ‘unsustainable’ rent hikes, report says

![]()

There is immediate demand for housing for between 500 and 600 graduate students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a need to build even more as rents in and around Cambridge rise beyond what students can afford, according to a long-awaited study group draft report released Tuesday by Christine Ortiz, the school’s dean for graduate education.

The recommendation to build up to 1,000 units – including “swing space” needed for when MIT renovates existing residences – more than triples the amount of housing already announced for the institute’s plan to remake 26 acres of its East Campus in Kendall Square. It also prods the school back toward a vision for housing it pursued for about four decades, until 2004.

“Our vision is essentially the vision embedded in the Bush-Brown report … which recommended that MIT house 50 percent of graduate students,” the report said. The school now houses 38 percent.

The policy ended with the arrival of president Susan Hockfield, said Cambridge resident Bob Simha, who served as MIT’s director of planning for four decades ending in 2000.

The report was “on the whole, a step forward,” Simha said.

Hope: As many as 5,000 units

Zoning for the Kendall Square plan passed in April amid complaints that there wasn’t enough low-priced MIT apartments to keep some 2,400 graduate students and others from competing to get market-rate rentals from other city residents. Critics inside and outside the school hoped MIT would build as many as 5,000 units, but the commitment was for about 300 instead, mainly high-end units (with 18 percent set aside for low-income tenants) built on Kendall Square’s canal near an anticipated retail center.

In winning its zoning, the institute said its plans for Kendall remained flexible and promised the Graduate Student Housing Working Group to look at housing needs for the MIT community. It created the group in March and promised a report by July, making Tuesday’s release of a study bearing a Jan. 16 date roughly six months late. Ortiz was asked Tuesday afternoon to comment on the delay.

The draft report can be read here.

The trends

The 11-member working group noted that the graduate population rose to just over 6,500 last year, a 7 percent increase in a decade, but said the population pressure could ease a bit in the short term.

“The overall forecast is that the number of graduate students will not grow in the near future, and, in fact, it may decrease slightly,” they said in the draft report. But just as the wider Cambridge and Somerville real estate vacancy rate is a tight 2 percent, “graduate housing on the MIT campus is close to full occupancy. Some rooms become available when students graduate or move off campus during the academic year, but they are typically filled relatively quickly. Thus, while the graduate housing on campus is never at 100 percent occupancy, few rooms remain empty for long. This is true for every dorm on campus.”

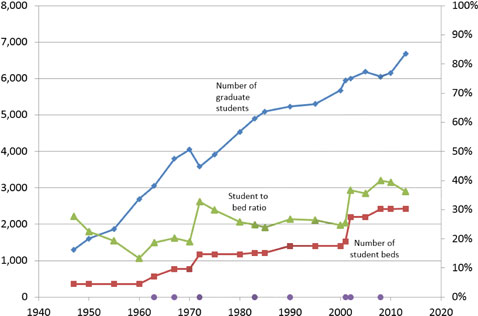

A graphic in the report shows the number of on-campus beds per grad student going back decades, with purple dots showing the opening of grad student dorms:

Meanwhile, “Cambridge rents are rising at a rate that appears unsustainable for graduate students” and the problem is expected to worsen with the nearly 4 million square feet of office and research and development space under construction in Cambridge, including the 87 percent identified by the city’s Community Development Department as going up in the neighborhoods nearest MIT.

Based on development statistics and a city study, the study group estimated that the new facilities could attract at least 8,000 employees, and “that 1,600 to 3,200 of these employees may live in Cambridge and produce demand for 400 to 1,700 units of rental housing.” (The city is working out its own such estimate in a “nexus study” approved by the City Council in May.)

Despite rent already making up about half of grad student stipends, increasing that pay or giving students money to meet rent hikes some other way wasn’t recommended:

We are already at or near the upper limit of what sponsors will support. While we will need to increase stipend support modestly, the increases will be nothing like the rates at which local rents increase. Second, giving students more money would likely heighten competition and tensions with local residents. Last, we believe that if students had more cash for local private rents, it would not increase the supply of affordable housing, but it very well might further inflate the cost of area housing.

With renovation of several student residences planned for the next decade and each facility needing to be empty for a year or more, the study group said MIT will need a new 400-unit residence hall to provide “swing space” to house displaced students and families.

After a renovation period of five to 10 years, “this swing-space housing would be added to the graduate housing stock to meet the demand that will develop over the next decade,” the draft report says.

More recommendations

The study group called for buildings that could house student families as well as single students:

Apartments could include “micro units,” studios and multiple-bedroom suites. A two-bedroom apartment, for example, could house a family one year and two unmarried roommates the next.

It also suggested that MIT look at partnerships or master leases in development that don’t “displace Cambridge residents” and – likely keeping in mind recent developments such as the canal-side units and Forest City building outside Central Square – the study group reminds that “the primary purpose of this effort would be to provide housing, not general MIT real estate investment.”

Staff should be appointed to explore the possibilities, the study group said. Existing dorms could be enlarged or other buildings could be repurposed, and MIT could look into copying Harvard and Boston University, which have turned privately owned hotels into student residences.

“We do not take it as part of our charge to specify how the institute meets these needs,” the study group said.

Wow, who coulda seen that one coming?

MIT is doing a tremendous disservice to its graduate students and to its host city for leaving this problem go unaddressed for so long. I would like to see the city work with the university to get more grad student housing built ASAP. If our current elected officials won’t do it, I’m ready to support anyone who will.

To answer my own question, judging by the presentation at MIT tonight, not the people doing the East Campus plans. Their proposals include possible demolition of Eastgate with no promise of replacing it and the passing mention of possible housing where Cambridge Trust is currently located. But it’s OK, we were told, because housing wasn’t part of their mission, even though it was all over the comments from the previous MIT and community meetings that we were given for reference. They’ll get to it, don’t you worry about that. They’ll get to it. Honest.

When do we get to start ushering grad students into $1500/mo+ micro-units? I realize that the preferred mantra of the Cambridge Day scene is of the sky-is-falling variety, but I don’t know how anyone could read that report and then publish non-sense like this. MIT has fallen short of a previous goal of housing 50% of grad students. True, they house roughly 38%. However the vast majority of those grad not living on campus all were very satisfied with their housing options. Some students seemed worried about rising rents. True, if they said, “No, I think rising rents are awesome.” I think there would be more cause for concern. Further, linking to a “No Money” article is the journalist equivalent of 3-Card Monty. His article is based on nothing, his research is in the form of regurgitated factoids spouted off by disgruntled MIT faculty who are under the impression that a degree is chemical engineering is akin to one in urban design. The report also said that the population of grad students is likely to go down and will flux. I do not see the need for 1000’s of units to accommodate for a dwindling population of people who seem to be happy where they are. The report also presupposes that these new units that will be created for students will cost the same as the current rate units. I’d say that is probably wishful thinking. The report also said that singles tend to go for $1200-ish, with doubles at $1800-ish… why would people who tend to like living in groups opt for a single in Kendall when they can rent a bed in a two thousand sqft apartment with a yard for only $800/mo? I realize that this site isn’t designed to illicit rational conversation, so I apologize for my continued insistence on it. I guess the funny pages have a place in journalism too.

Patrick, what would you propose to address the problem of insufficient housing and rising rents in Cambridge?