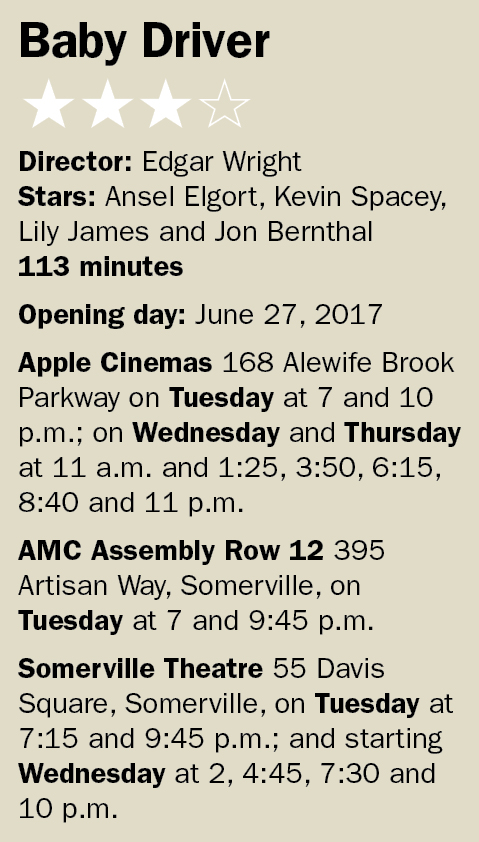

‘Baby Driver’: Kid is pure hell on wheels, but diner waitress reminds him of mom

Edgar Wright, the man behind the edgy romps “Shaun of the Dead” (2004) and “Hot Fuzz” (2007), comical deconstructions of the zombie and cop buddy genres, as well as the quirky, if not gonzo, adaptation of the graphic series “Scott Pilgrim” – as “Scott Pilgrim vs. the World” (2010) – moves into far darker territory with his latest, “Baby Driver.” The project may have taken root as a result of Wright’s affiliation with Quentin Tarantino on the 2007 B-flick homage “Grindhouse,” but the texture isn’t so much Tarantino pulpy as it is the kind of criminal abyss you might find in a Nicolas Winding Refn film if served up with the kitschy kinetic flourishes of an unbridled Luc Besson.

The film, in short, is an adrenaline shot that never lets down. You won’t get a chance to go to the bathroom – but also, because of the breakneck pace, the audience never gets a chance to get caught up emotionally. Wright gets right to it as a squad of robbers (played by Jon Bernthal, John Hamm and Eliza González) and their driver, the titular Baby (Ansel Elgort) hold up a bank. We don’t go into the bank for the job, but hang out in the car with the aptly named wheelman (née boy), who has the fresh face of a J. Crew model and doesn’t appear old enough to drink, listening to tunes on his iPod and playing air guitar. It’s a cute moment, but after a bit it becomes clear it lacks the energetic virility of Tom Cruise in his skivvies in “Risky Business.” Blessedly, the robbers pour out of the bank with the heat hot on their tail, and this is where Wright and the film really kick it up. Baby’s got Mario Andretti skills and Steve McQueen cool, and to prove the point we get an endless phalanx of blue and whites to chase Baby’s hot red Subaru through the streets of Atlanta. Cars crash, traffic backs up and there’s nothing Baby won’t try as the net tightens. Wrong way down the freeway, no problem.

The film, in short, is an adrenaline shot that never lets down. You won’t get a chance to go to the bathroom – but also, because of the breakneck pace, the audience never gets a chance to get caught up emotionally. Wright gets right to it as a squad of robbers (played by Jon Bernthal, John Hamm and Eliza González) and their driver, the titular Baby (Ansel Elgort) hold up a bank. We don’t go into the bank for the job, but hang out in the car with the aptly named wheelman (née boy), who has the fresh face of a J. Crew model and doesn’t appear old enough to drink, listening to tunes on his iPod and playing air guitar. It’s a cute moment, but after a bit it becomes clear it lacks the energetic virility of Tom Cruise in his skivvies in “Risky Business.” Blessedly, the robbers pour out of the bank with the heat hot on their tail, and this is where Wright and the film really kick it up. Baby’s got Mario Andretti skills and Steve McQueen cool, and to prove the point we get an endless phalanx of blue and whites to chase Baby’s hot red Subaru through the streets of Atlanta. Cars crash, traffic backs up and there’s nothing Baby won’t try as the net tightens. Wrong way down the freeway, no problem.

There’s more to the movie and more high-energy car chases that will leave your jaw on the floor, and it’s impressive how Wright has done it. Like George Miller did with “Mad Max: Fury Road,” Wright’s gone old school and resorted to good, old-fashioned stunt driving with little reliance on a green screen or the type of special effects antics one typically sees in the “Fast and Furious” series – a fine enough series, it’s just that you don’t drink in any palpable artistry or risk in such endeavors. William Friedkin would be proud.

Of course Baby has a backstory. Lost mom and dad early, grew up in a foster home, began boosting cars early and one night, picked the wrong Mercedes to take for a joyride. That tricked-out Benz full of merch belonged to an enigmatic bigwig by the moniker of Doc (Kevin Spacey, who else?) with the cops in his pocket and a crime ring he runs out of an old warehouse, much the way Lawrence Tierney and Chris Penn as father and son did in “Reservoir Dogs.” Doc basically owns Baby, and Baby’s got vulnerabilities too, be it his deaf foster dad (C.J. Jones, the film’s heart and soul) and Deborah (Lily James, so good in Kenneth Branagh’s recent “Cinderella”), the waitress he pines for who works in the same diner his mom did and has the same melodic country voice when she dips into tune, as she often does.

Besides the chase sequences, what makes “Baby Driver” go is the hot potpourri of personalities Baby gets paired with – he’s the perennial good luck charm and get synced up with rotating crews. The standout is clearly Jamie Foxx’s edgy smooth muscle, Bats, but Hamm and González are a joy as the criminally wedded couple, while Bernthal and Lanny Joon prove peevishly distracting in brief bits.

Elgort, who came to rise through the “Divergent” series, fills the lead role effectively enough. The shortcomings aren’t really his fault, as Baby is more of a concept than a character – a tune-addicted, hearing-impaired pretty white boy with a black foster pop – that’s a lot to bite off, and then there’s his romantic obsessions with mom. Ryan Gosling’s getaway driver in Refn’s “Drive” (2011) was a far more complex and real incarnation; the troubles and vulnerabilities there felt foreboding and genuinely off the street. Wright, like Tarantino, is a master of his craft and knows how to imbue it with quirk and wit in a seamless way, the main difference between the two being that while both wrap their arms around high concepts, Tarantino is character obsessed, and in that obsession comes the soul that drives and binds.

Tom Meek is a writer living in Cambridge. His reviews, essays, short stories and articles have appeared in the WBUR ARTery, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, The Rumpus, The Charleston City Paper and SLAB literary journal. Tom is also a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics and rides his bike everywhere.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks