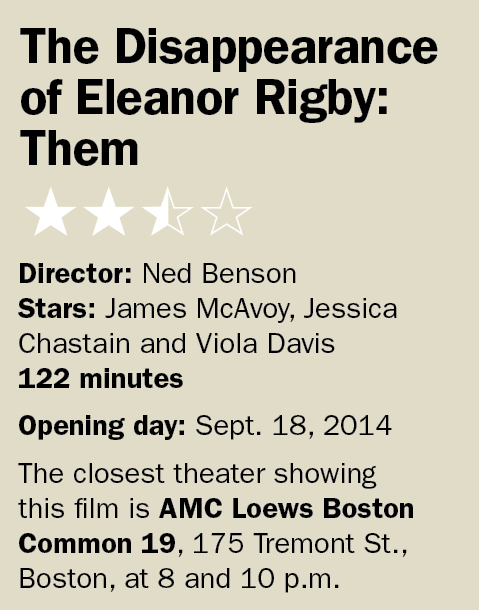

‘Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby: Them’ couple torn apart in film stitched together

![]()

Ned Benson’s meaning-of-life contemplation revolves around a couple in turmoil. Right from the start “The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby: Them” sets the table as the Eleanor of the title (Jessica Chastain) and her husband, Conor (James McAvoy), appear the part of the perfect couple doing the casual fine-dining thing in a swank New York eatery – when they decide to up and split on the bill. It’s not that they can’t afford din-din, it’s just their united expression of freedom, frolic and a strange sense of foreplay. The scene is short and sweet. In the next, and at some future time, we catch Eleanor (named after the Beatles song) walking her bike across a bridge. She’s despondent and troubled, and in a flash, she’s over the rail.

The effects of the suicide attempt (and that’s no spoiler; it comes in the first few frames) spiral outward in ways that divide and redirect in sudden and sometimes jarring directions. Eleanor hurts others as much as she hurts inside. Following the failed attempt, triggered by the death of their son – an event far from the main narrative, but ever looming – Eleanor takes up recovery at the modest, yet stately Connecticut home of her parents (played by William Hurt and the ever exquisite Isabelle Huppert). When asked what they or anyone can do to help, she vacantly responds that she doesn’t know. Not because she’s being coy or wants to be left alone, but because Eleanor is genuinely at a loss as to what is next in her life. The one certainty is that Conor is too close a reminder of what happened, and Eleanor blames him to some degree for the way he tried to move on after the loss of their son (putting the child’s belongings in the closet and ordering Chinese). So he is left in the dark as to her whereabouts.

The effects of the suicide attempt (and that’s no spoiler; it comes in the first few frames) spiral outward in ways that divide and redirect in sudden and sometimes jarring directions. Eleanor hurts others as much as she hurts inside. Following the failed attempt, triggered by the death of their son – an event far from the main narrative, but ever looming – Eleanor takes up recovery at the modest, yet stately Connecticut home of her parents (played by William Hurt and the ever exquisite Isabelle Huppert). When asked what they or anyone can do to help, she vacantly responds that she doesn’t know. Not because she’s being coy or wants to be left alone, but because Eleanor is genuinely at a loss as to what is next in her life. The one certainty is that Conor is too close a reminder of what happened, and Eleanor blames him to some degree for the way he tried to move on after the loss of their son (putting the child’s belongings in the closet and ordering Chinese). So he is left in the dark as to her whereabouts.

The film’s pronoun qualifier, “Them,” is symbolic mostly in the packaging of Benson’s directorial debut – which more aptly could be tagged a “debut trilogy.” Last year at the Toronto International Film Festival, he introduced two other “Rigby” versions, “Him” and “Her” (not to be confused with the recent Scar-Jo, Joaquin Phoenix and Spike Jonez collab), telling the same story of pain, love and hopeful reconciliation from the players’ different points of view. I have not seen either of those other “Rigby” versions and cannot comment on how they all work together as a collective “we,” but I can attest that “Them,” which according to reports was the Weinstein Co.’s idea to conjure up after “Him” and “Her,” works seamlessly and poignantly on its own.

The “disappearance” of the title too, like the protuberant pronoun, is a loaded and multi-faceted term depending on how applied and from whose POV. Conor can’t physically find his wife, Eleanor’s parent can’t find the vestige of the little girl they raised and Eleanor herself is at ambiguous crossroads. Things do ultimately shift and take new form. Eleanor enrolls in a class in the city (her fast food noshing sessions with Viola Davis’ prof. are leaden with stark revelation and sardonic sincerity) while Conor struggles to keep his gastro-bar afloat and deal with the specter of his father (Ciaran Hinds), a philandering restaurateur whose clientele are Hollywood A-Listers.

Much of the film’s burden falls on Chastain, and she is the engine of its success. Her Eleanor is both broken and fragile, yet steely and aloof. The actress’s alluring red mane and well-defined porcelain features deepen Eleanor’s indelible, enigmatic sheen. Chastain hasn’t demonstrated great range as of yet, but her presence – take her ethereal otherness in “TheTree of Life” or dogged resolve in “Zero Dark Thirty” – have elevated the films she’s been in. McAvoy, on the other hand, is adequate, buoyed by wide-eyed idealism and limitless, adoring love, but he isn’t as essential. He’s simply the other half of the marriage equation, which is ultimately more about “she” than “he.”

If there’s a real weak link to “Rigby,” it’s Saturday Night Live’s Bill Hader as Conor’s business partner. The casting otherwise is lethally spot on: Hinds and Davis provide sublime, yet subtle crutches through which the mains reveal, while Huppert and Hurt intrigue as the concerned parents. There’s not much of a life-partner thread between the two, which may be an underscoring point of the film – she’s a French expatriate bearing some rue for choices made, and Conor and Eleanor too carry a strange push-and-pull dynamism in the paths they choose and their emotional comport in the wake of tragedy. In other incarnations – and other hands – “Rigby” could have been a maudlin, Hallmark exercise, but what Benson has achieved is a haunting slow burn that lingers.

![]()

Tom Meek is a writer living in Cambridge. His reviews, essays, short stories and articles have appeared in The Boston Phoenix, The Rumpus, Thieves Jargon, Film Threat and Open Windows. Tom is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics and rides his bike everywhere. You can follow Tom on Twitter @TBMeek3 and read more at TBMeek3.wordpress.com.