Harvard’s Cooke led new chemistry department, but Francis Prince Clary was who made it bubble

Josiah Parsons Cooke, the Erving professor of chemistry and mineralogy at Harvard. (Photo: William Shaw Warren via Wikimedia Commons)

Today, Cambridge is a world center of biotechnology and biochemical engineering. But in the early years of modern chemistry, U.S. chemists lagged far behind their European counterparts. In the 1850s, Harvard began building what would later be seen as one of the most forward-thinking university chemistry departments in the country.

Francis Prince Clary was there.

At about the time Clary moved to Cambridge in 1848, Josiah Parsons Cooke graduated from Harvard. Cooke had taught himself experimental chemistry, which was barely taught when he was a student. In May 1850, he was appointed the instructor in chemistry and mineralogy, and he provided his own lab equipment. In December of the same year, he was appointed professor and tasked with building a department from the ground up. He obtained leave immediately to tour Europe to buy equipment and attend lectures. On his return, he set up a small lab in the basement of University Hall.

Charles W. Eliot, later a chemistry professor at MIT and eventually president of Harvard, studied chemistry with and then assisted Cooke. He was considered one of the world’s foremost chemists by his death in 1894, after which Eliot wrote about his career – mentioning that for most of the 1850s “professor Cooke had had no visible assistance in the conduct of his department. He had himself paid for the services of Francis P. Clary, for many years his only assistant at his lectures, and he had received some volunteered assistance from students.”

In the 1860 census, Clary’s occupation is “servant.” In 1870, it’s “college janitor.” In 1880, it’s “janitor.” In one piece of Harvard-related literature, he’s “the colored janitor of Boylston Hall,” built in 1858 at Cooke’s instigation to house a proper chemistry lab and classrooms. But for most of his career, in addition to whatever janitorial duties he fulfilled, Clary was, at the least, Cooke’s chemistry preparator and, more likely, junior partner in his experiments.

Boylston Hall, where Clary and Cooke worked together, about 1858. (Photo: Class of 1861 album of Stephen Williams Whitney, 1861/Harvard University Archives)

Modern chemistry was still in its infancy – Mendeleev’s periodic table didn’t exist yet. Cooke was making and testing classifications of elements to understand and predict how each element would behave. It hardly seems likely that Cooke valued Clary’s help enough to pay him out of his own pocket yet was simply telling him to move flasks and tubes around, and Clary was present during all of Cooke’s lectures and demonstrations, which is why all Harvard students knew him and might want a photo of him in their personal class albums. By the late 1850s, he would have had a fund of theoretical and practical chemistry knowledge far exceeding any of the incoming junior faculty such as Eliot.

In 1914, the Harvard Graduates’ Magazine published a reminiscence of “certain frequenters of the Yard, along about the sixties,” including a view of Clary in lectures:

“Let us step into Boylston, and note where the unflinching Clary stands, amid all the congregation of salts and acids. The arcana of solutions and precipitates (some of which work and some don’t), the furious bubbling, and the clouds of noxious gases pale not his dusky cheek. Nay, even though the experiment be at once the most unintelligible and the most hazardous known to science, Clary goes ahead, pumping and emptying and mixing, as serene as if he were the holder of a paid-up policy in a first-class insurance company.

“You recall, sir, the universal belief that this important factor in the curriculum was ticketed for a farewell exit (we knew not what moment) up through the roof, shot skyward with the debris of apparatus, and the fragments of an exploded formula: all of which would be adequately explained at the next lecture …”

Chemistry demonstrations are inherently theatrical, akin to magic shows in many ways. To the knowledgeable, everything is predictable and under control, but to the unschooled, disaster is always potential. Perhaps unknown to the student, Clary’s serenity reflects his chemistry knowledge: He knows he’s not doing anything dangerous.

“This important factor in the curriculum” apparently forged some kind of relationship with students that was more personal than just appearing before them in demonstrations. In the July 1881 issue of The Harvard Register, an article titled “The Veterans of the University” gave short sketches of living men who had worked at the university for at least 20 years. The sketch of Clary states that “he has a ‘benefit’ once a year, when he provides rooms and luncheon for the Class elections.” Renting or preparing rooms and catering a lunch wouldn’t be inexpensive, and the fact Clary did this year after year means the students must have been respectful of his generosity and also that he must have derived some considerable satisfaction from hosting the students, all of whom would have spent time with him in required chemistry classes. Clary and his wife, Maria, also housed at least one student during Clary’s career at Harvard: first-year student John Henry Wheeler, from Woburn, Class of 1871, who was later professor of Greek at the University of Virginia.

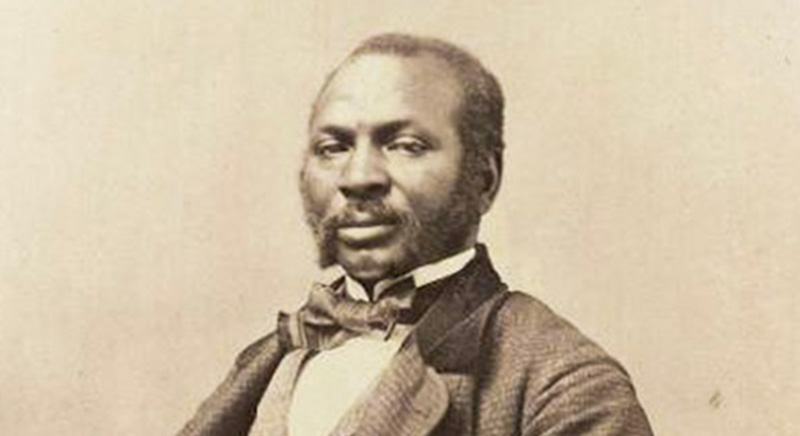

Aaron Molyneaux Hewlett, instructor and curator of the Harvard gymnasium, would become Clary’s close friend. (Photo: George Kendall Warren via Wikimedia Commons)

Another important development at Harvard for Clary was the arrival of Aaron Molyneaux Hewlett to take command of the new gymnasium in 1859. Hewlett wasn’t a member of the faculty, but he was the first Black instructor – a breakthrough. He and his family were new to Cambridge, and Clary and other members of Cambridge’s Black community surely welcomed him, because within a very few years Hewlett was in business with some of them. Clary and Hewlett were about the same age. Both occupied unusual positions on campus, and both were Masons. Both were involved in civil rights work, with Hewlett petitioning public authorities regarding instances of discrimination against him and his family on transportation and in places of entertainment. Evidence shows that the two families, whose children were alike in age, grew close.

Hewlett died rather suddenly in 1871 of a brain abscess. His wife, Virginia, and children remained in the family home on Dunster Street, but eventually moved to Washington, D.C. – Virginia first to live with daughter Virginia, who had married Frederick Douglass Jr. Hewlett was buried in Cambridge Cemetery, as eventually were others of his family. Clary’s family plot is only a few yards away. When Hewlett’s son Paul Molyneaux Hewlett, an actor known in the United States and England for his portrayal of Othello, died in 1891 in Washington, D.C., his body was brought to Cambridge and the funeral held at the Clarys’ Roberts Road house.

The Clary connection to Harvard continued even after Francis Prince Clary’s death.

![]()

About the Cambridge Black History Project

The Cambridge Black History Project is an all-volunteer organization of individuals having deep roots in Cambridge. We are committed to researching, accurately documenting, preserving and illuminating the journeys, accomplishments and challenges of Black Cantabrigians, and to raising awareness of their stories through educational outreach to the Cambridge community and beyond.

The Cambridge Black History Project is an all-volunteer organization of individuals having deep roots in Cambridge. We are committed to researching, accurately documenting, preserving and illuminating the journeys, accomplishments and challenges of Black Cantabrigians, and to raising awareness of their stories through educational outreach to the Cambridge community and beyond.

Special thanks for research help to Charles Sullivan and the staff at the Cambridge Historical Commission and Alyssa Pacy at the Cambridge Public Library Cambridge Room.