Pillars of abolitionism and of their communities, but the family home is paved, the Clary name lost

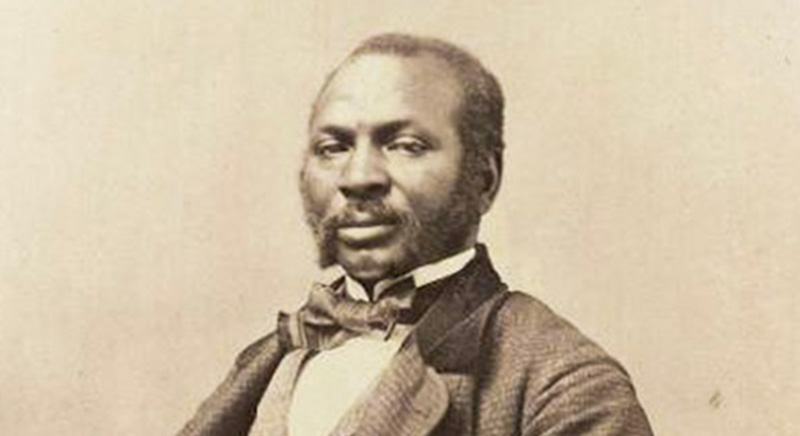

Francis Prince Clary was photographed more than once for Harvard class albums. This photo was taken in 1858 or before. (Photo: Harvard University Archives)

The hope engendered by the Union’s victory in the Civil War and Reconstruction in the South didn’t lead to any major diminution of prejudice and discrimination in the North. But Aaron Molyneaux Hewlett, Harvard’s gymnasium manager and instructor and first Black staff member, and Francis Prince Clary, unofficial member of the chemistry department, saw the arrival of the college’s first Black students: Richard Greener in 1865 and Emanuel Sullavou in 1866. It’s interesting to contemplate the conversations Clary and Hewlett, experienced in Harvard’s and Cambridge’s ways, might have had with these young men. By 1873, Clary and Sullavou – who would become a prominent lawyer in New Bedford – were fellow officers in the Prince Hall Grand Lodge, Sullavou as grand corresponding secretary and Clary as grand organist.

By the 1880s, Francis and Maria Clary were respected elders in Cambridge’s Black community and beyond. Daughters Emily and Hannah Lizzie had graduated from Cambridge High School in the 1870s. The family worshipped at the Shepard Memorial church (now First Church), and held church neighborhood meetings in their Roberts Road house. In the 1881 Boston Directory, Clary was listed as the “most excellent high priest” of the St. Stephen’s Chapter of Royal Arch Masons, Prince Hall Grand Lodge. He had been a lodge brother for decades, mentioned in reports of important ceremonies honoring the local heroes of the abolition movement.

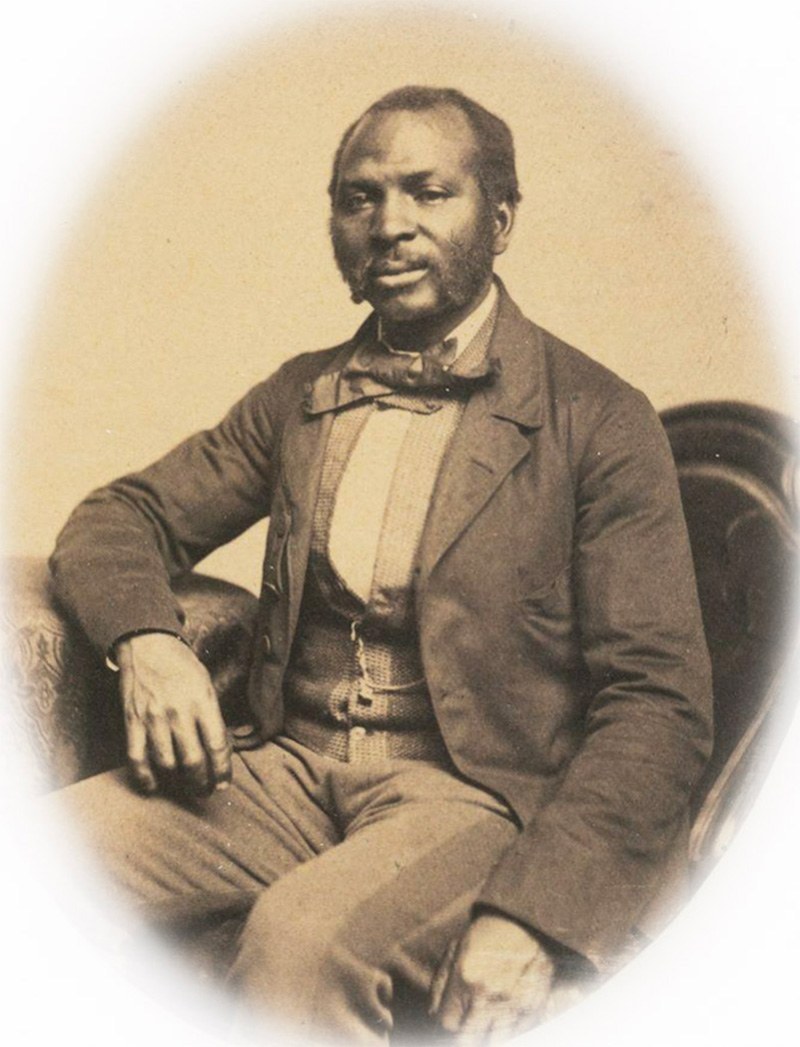

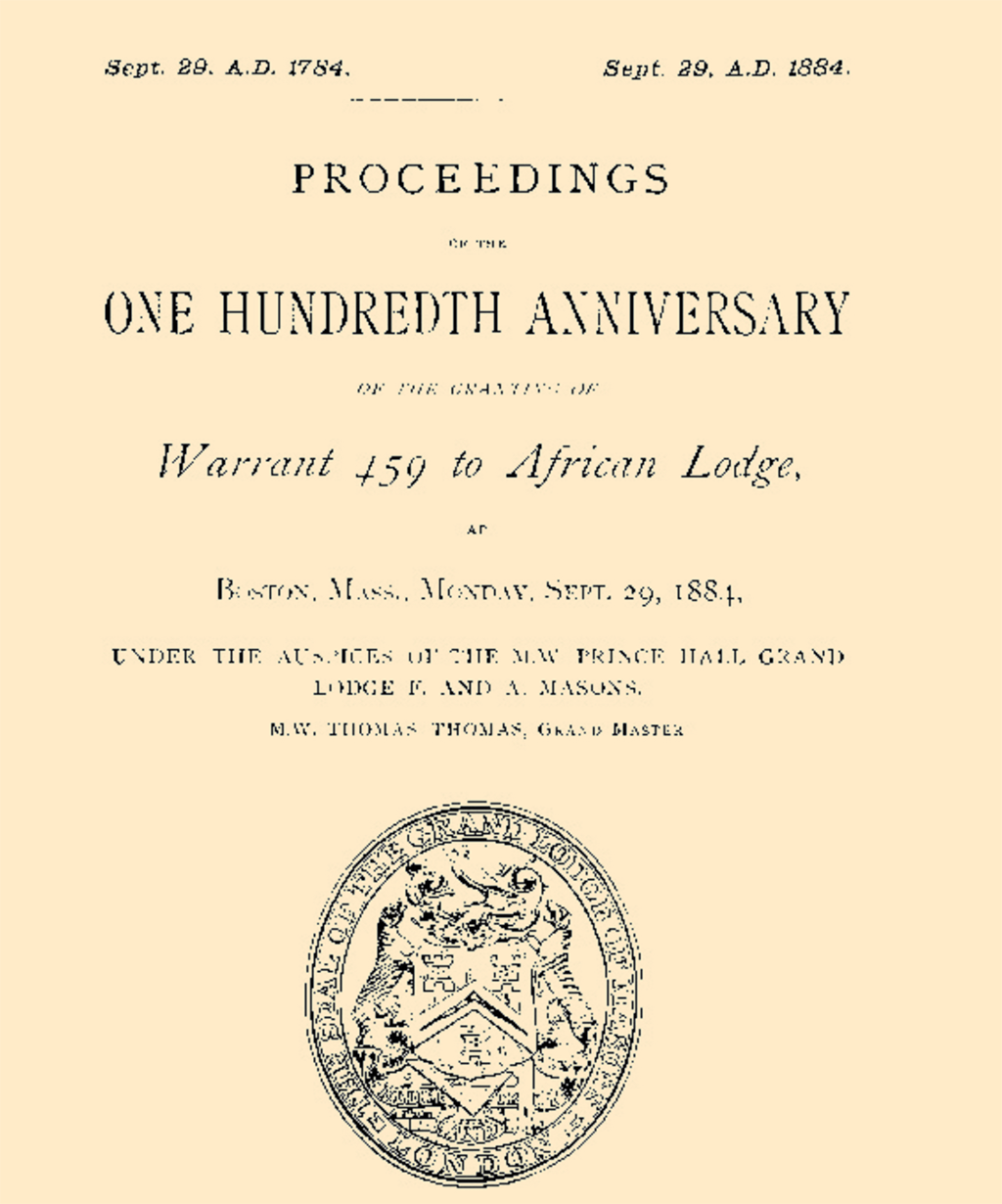

In 1884, the Prince Hall Lodge celebrated in Boston the 100th anniversary of the granting of its warrant. “Past deputy grand master F.P. Clary” rode in the third carriage of eight preceded by mounted police, four marching bands and hundreds of marchers parading through the West and North Ends to Copps Hill and the grave of Prince Hall, then through Scollay Square to Tremont Temple for services and an address by Lewis Hayden. This was followed by more remarks, a reception, a promenade concert and a banquet. Clary, wearing a yellow rosette, was the floor marshal.

Clary played an important role in a Mason’s anniversary ceremony. (Image: Library of Carter G. Woodson and Association for the Study of African American Life and History Library, Emory University)

But by the late 1880s, Clary was ailing. He died Aug. 1, 1888. An obituary in the Boston Evening Transcript described him as “custodian of the Harvard Chemical Laboratory for nearly his entire adult life”; a “natural musician” who played and taught the violin, piano, harp, guitar, banjo, cornet and flute; “prominent in Masonry”; and a man who “held the esteem of the entire community.”

Hannah Lizzie died the next year at age 31 of “phthisis,” probably tuberculosis; unlike Emily, she had not had an occupation reported for many years, and so may have been unable to work for most of her adulthood. The report of her funeral shows Black Cambridge gathering to offer up its condolences.

Maria and Emily stayed on in their house. Emily remained unmarried. She participated in community committees and fundraising events with Cambridge’s most established Black women, including Maria Baldwin and Nancy Poole Lewis, married to Emily’s first cousin George W. Lewis, steward of Harvard’s Porcellian Club, like his father before him. Nancy Lewis ran a highly respected dancing school for upwardly mobile Black children from Cambridge and Boston, and Emily was one of the “patronesses” of their ballroom dances.

By now, Emily too was a fixture on the Harvard campus, well-known to generations of students. In 1923, W.E.B. Du Bois’ magazine The Crisis pointed out that Emily had been “filling a unique position for over 50 years.” Cooke, it said, had hired her straight out of high school to be the chemical laboratory’s storeroom clerk. Without saying so, the description of her job makes clear that Francis had schooled his daughters in chemistry, almost certainly imparting more knowledge than they would ever be offered in school. (Du Bois, of course, would have known Emily when he was a Harvard student.)

Maria Jane Lewis Clary died in 1900. Emily lived until 1940. She remained in the Clarys’ Roberts Road house until about 1906, soon after moving to live on Parker Street among her Lewis cousins and others who remembered the decades following the Civil War – when, despite continuing discrimination, Boston and Cambridge at least talked a good game about honoring its Black and white abolitionist heroes and it seemed that Black men, at least, were beginning to come into their own, winning seats in state and local government.

But by the time the Crisis article had appeared, white immigrants had swamped the Black population. Harvard had banned Black students from the dorms because the president buckled to white students’ objections. D.W. Griffiths’ racist silent movie “Birth of a Nation” (1915) had been shown in Boston, despite huge efforts by the Black community and its few allies to ban it. What must Emily Clary and her Lewis relatives – Harvard insiders – have felt reading Samuel F. Batchelder’s “Wanted! College ‘Characters’” in the Harvard Alumni Bulletin of June, 8, 1922, dismissing Francis Prince Clary as “the darkey janitor and factotum of the laboratory in Boylston Hall”?

Clary and his family are buried in Cambridge Cemetery. (Photo: Peter Loftus)

Francis Prince and Maria Lewis Clary’s house is now the site of a parking lot serving Spaulding Hospital. Their names are not among those familiar from histories of the Black abolitionists. But in their time, they were among the community’s pillars and would have been recognized by most Cantabrigians and all Harvard men whenever they were out and about the city. Harvard has forgotten them.

The Clarys have no direct descendants to tend their family’s grave monument. The Clary and Hewlett monuments in Cambridge Cemetery are falling prey to the elements. Perhaps Harvard might feel some responsibility to remember these men and their families, persistent civil rights activists, who were clearly not just at Harvard but truly of Harvard, foundational to the building of the chemistry and athletics departments.

The Clary family monument in Cambridge Cemetery. The tall monument to the right is the Hewlett family monument. (Photo: Peter Loftus)

![]()

About the Cambridge Black History Project

The Cambridge Black History Project is an all-volunteer organization of individuals having deep roots in Cambridge. We are committed to researching, accurately documenting, preserving and illuminating the journeys, accomplishments and challenges of Black Cantabrigians, and to raising awareness of their stories through educational outreach to the Cambridge community and beyond.

The Cambridge Black History Project is an all-volunteer organization of individuals having deep roots in Cambridge. We are committed to researching, accurately documenting, preserving and illuminating the journeys, accomplishments and challenges of Black Cantabrigians, and to raising awareness of their stories through educational outreach to the Cambridge community and beyond.

Special thanks for research help to Charles Sullivan and the staff at the Cambridge Historical Commission and Alyssa Pacy at the Cambridge Public Library Cambridge Room.