Idea of city-owned broadband disappeared, but conversation’s return might disappoint

The long-missing topic of municipal broadband is returning to public discussion Monday, with a City Council order inspired by both some local schoolchildren’s lack of Internet access and steps taken by a Republican-led Federal Communications Commission toward undoing net neutrality laws, which keep the Internet a level playing field.

The long-missing topic of municipal broadband is returning to public discussion Monday, with a City Council order inspired by both some local schoolchildren’s lack of Internet access and steps taken by a Republican-led Federal Communications Commission toward undoing net neutrality laws, which keep the Internet a level playing field.

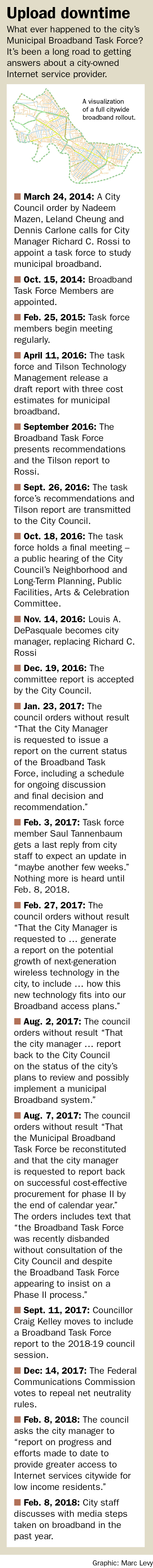

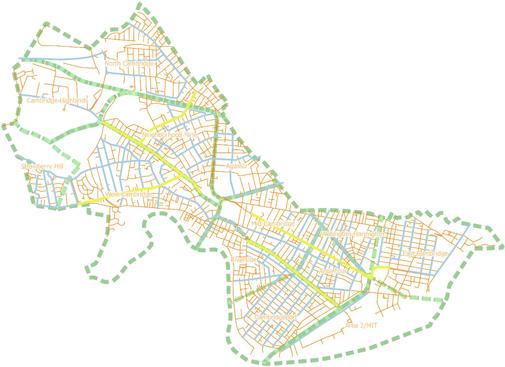

A task force appointed by the city manager in October 2014 to look into building a city-owned network for Internet – for anywhere between $5.5 million and $187 million, depending on approach – had gone silent since issuing a report in September 2016 and a final meeting a month later. It’s been a source of confusion and frustration for some of its members, residents and elected officials.

Three policy orders issued by the City Council last year to hear about the task force findings went unanswered; councillor Craig Kelley made sure that the issue moved to the current term’s list of awaited reports, and vice mayor Jan Devereux expressed interest Monday on taken it up in her Transportation & Public Utilities Committee – and then signed onto an order by councillor Quinton Zondervan with Mayor Marc McGovern and councillor E. Denise Simmons.

She’d previously signed onto the most aggressive council broadband order of the previous term, urging “that the Municipal Broadband Task Force be reconstituted” after being “recently disbanded without consultation of the City Council and despite the Broadband Task Force appearing to insist” on a Phase 2 to answer questions raised in its Phase 1 report process. A report by the end of the year was demanded, but councillors never heard back.

Abandoned or on hold

In the silence that followed their report, task force members said, they also heard nothing back from city managers and staff, including director of communications and community relations Lee Gianetti, who worked with them closely. One member referred to the task force as “abandoned.”

Member Saul Tannenbaum said his final contact from the city, amid many attempts at dialogue, was more than a year ago. “I am not ready to update the task force on our progress,” Gianetti says in that Feb. 3, 2017, email. “I was hoping to send an email out last week, but it may be another few weeks.”

Another task force member, Ben Compaine, agreed that he had “tried to talk to Lee … and haven’t gotten any callbacks or response to emails. It’s disappointing there’s been no follow-up.”

In an effort to figure out what was happening with his own task force, Tannenbaum said silence from Gianetti and City Solicitor Nancy Glowa forced him to appeal to the state to say if members were still covered by Open Meeting Law – and they were.

“Which means, for example, if the task force wanted to get together to write a letter to the city saying ‘What’s going on, what are you doing with our work?’ that’s a meeting that would have to be called by the city and put on the public schedule and noticed like any kind of open meeting,” Tannenbaum said. “So we would need the city’s approval and active cooperation to actually complain about the city.”

City staff didn’t drop it

Asked recently about the task force, Gianetti said the city would be deciding in the next “three to six months” what a next step might be.

As to the council’s belief that the task force had been disbanded, “the task force completed its charge, and there’s no new charge now,” Gianetti said. “So whether it’s disbanded or not, it’s on hold.”

But city staff have not been inactive on the topic, he said Thursday.

“For the past year, city staff have been holding internal discussions to evaluate options for the city’s next steps. Numerous meetings and conversations have been held with consultants, industry experts and telecommunication/broadband companies. In fact, the city has had two such meetings this week,” Gianetti said. “We recognize that there are digital equity issues in our city, and we are focusing our attention on creating a recommendation to the city manager on how we can address this important topic.”

Lee Gianetti worked closely with the Municipal Broadband Task Force and has continued working on broadband issues in the past year. (Photo: Ceilidh Yurenka)

There is not enough dissatisfaction with current options, need or money for a full city-owned network to be rolled out, Gianetti said.

“While we do receive complaints about only having a single cable provider in the city, we do not see evidence that the broader community identifies a municipal broadband system as a critical issue facing our city. The potential for a $200 million capital investment to build a fiber broadband system in Cambridge make such a project not possible. The city’s commitment to addressing affordable housing, expanding early childhood education, investing in safe street infrastructure, a $500 million school reconstruction program and improving the conditions of municipal facilities like fire stations – to name a few – are substantial financial investments, and funding for a municipal broadband system would directly compete with these priority areas.”

Changing situation

The new council order asks for an update on efforts to help low-income residents and “future actions to be taken which will improve digital access throughout the city,” with an eye on likely price increases resulting from changes since the task force last studied the situation in mid-2016.

That’s not just in terms of technology – startups such as Starry, of Boston and New York, and Allston-based netBlazr are exploring wireless solutions; telecom giants including AT&T and Verizon have launched so-called 5G networks – but politically. Since the elevation of Ajit Pai to lead the Federal Communications Commission, the agency has rescinded Obama-era privacy regulations preventing Internet service providers from monetizing customer use data; voted to end net neutrality; and killed the Lifeline program, which subsidized Internet usage for low-income people.

A team from Allston-based netBlazr installs wireless Internet equipment in Boston’s Castle Square in 2012. (Photo: netBlazr)

Ensuring every resident has the same access to fast, reliable Internet – filling in what’s called the digital divide – was identified as a priority from the creation of the task force, called for in a March 2014 council order, and again as a big part of the expected Phase 2. “Affordability and equity” was the first-listed goal in the task force report, which was written by the consultant Tilson Technology Management.

Municipal network ownership would be helpful to the 9.2 percent of Americans lacking broadband, because it’s cheaper than commercial services and doesn’t come with prices that balloon after low introductory rates, according to a study published last month by Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society; a phone survey cited in the Tilson study suggested that only 5 percent of high-earning Cambridge households didn’t have Internet access at home, apart from mobile, compared with 33 percent nationwide. But Census figures suggest up to 60 percent of lower-income Cambridge households lack broadband.

Compaine believes the imminent end of net neutrality rules is “totally irrelevant” to the work of the task force (and came out of the process unconvinced a municipal broadband network was needed), and Tannenbaum doesn’t think it deserves more attention than the FCC’s other consumer-unfriendly actions.

But it has drawn attention to the work of the task force.

“Certainly, around the country there’s much more interest … I’ve gotten email and calls from citizens in a couple of cities getting in touch to ask about what’s going on and how they should approach it. This has become much more of a mainstream thing because people are looking at the Trump administration and the corporate consolidation continuing to go on and just deciding they’ve had enough,” Tannenbaum said.

Potential groundswell

In the last few weeks, people in Cambridge not associated with the task force have “come out of the woodwork and reached out and asked what they can do,” he said. “There is the very beginnings of some sort of grassroots group to work with the council so it gets the attention it needs. These are just people who think this should be done – and there are a lot of them. This has broad public support, so far as I can tell.”

In neighboring Somerville, a group has organized a meeting about building community Internet – citing the end of net neutrality as a concern – from 1 to 4 p.m. Saturday at the Somerville Public Library, 79 Highland Ave., in the Winter Hill neighborhood.

Though Compaine also hears complaints about providers such as Comcast and Verizon and questions about when there will be a municipal broadband system, he said he doesn’t “see a movement at this point, or any sort of groundswell.” What he does see are some promising technological developments and a possible movement by the monopoly companies, albeit anecdotal, to improve a poor public image. And he worries about spending millions of dollars to potentially repeat a previous era’s mistakes.

“There was a time when everyone was installing Ethernet. And Wi-Fi came along, and now those Ethernet jacks are totally unused,” Compaine said.

Seeing flaws in the process

Tannenbaum, a believer in the long-term value of fiber-optic technology and a skeptic when it comes to relying on new technologies that remain untested on a large scale, called even an $187 million outlay for municipal broadband reasonable when compared with the city’s current capital projects – it’s around what the city is paying for each of three public school campus renovations.

But he has other reasons to wonder at what will emerge when City Manager Louis A. DePasquale finally reports back, namely that he isn’t sure DePasquale is getting the best information from the consultant’s report.

“The consultant’s report gave us three options, and we rejected them all for a variety of different reasons,” Tannenbaum said. “The interaction between the task force and the consultant was very limited by city staff by design, and our ability to address the direction of the consultants was limited.”

Along with a feeling that Tilson never quite understood the city it was studying came results that tilted toward the negative, Tannenbaum said. (Beyond saying that the task force’s work city has given “a better understanding of the challenges facing the city in terms of broadband,” Gianetti did not address the critique directly.)

“We didn’t look at any of the benefits [in the Tilson study]. The city manager basically got a report on costs and risks and nothing about what this would do for the city,” Tannenbaum explained. “If all you know is what you read in the report, of course you’re not going to go forward. But the benefit here would be widespread, in ways we can’t actually imagine.”

On the other hand, Tannenbaum said, the Tilson report is “chock full” of important information that could be useful if the city followed a path toward municipal broadband.

“It’s not like this was a wasted effort,” he said.

This post was updated Feb. 14, 2018, to clarify household broadband access based on U.S. Census information.

Minutes of the Public Meetings held by the Cambridge Broadband Task Force Committee Appointees are now available, email https://www.cambridgema.gov/Departments/citymanagersoffice/contactus/contactus

Information about relevant background/skills/experience of Cambridge Broadband Task Force Committee Appointees should be made available online… Most haven’t made themselves available limiting civic engagement !