With no municipal Internet seen on horizon, users turn to patchwork of smaller initiatives

At the Cambridge Public Library, patrons are limited to two hours of computer access per day. (Photo: Jessica Lau)

Like most residents, Kathy Watkins does not have much choice for getting Internet at home: either buy the service from Comcast, or go without.

“I have a hard time affording Internet in Cambridge,” she said. “Every year it just keeps going up and up. I call and beg and they say, ‘We’ll give you a deal,’ until a certain point and then they just won’t.”

Watkins said she considers herself lucky. “There are a lot of low-income people who can’t afford it at all,” she said. “And it’s not something that people can get by without these days, if you want to access benefits and job applications and college.”

A significant number of Cambridge residents lack Internet access at home, and stopgaps such as using computers at public libraries have limitations. Since federal support for advancing Internet access has waned, Cambridge residents are turning to local efforts to improve their situation.

The Federal Communications Commission recently repealed regulations that protected net neutrality, the concept of equal access to all data on the Internet. The repeal went into effect June 11. But the regulations were not just about net neutrality – they had also promoted fair access to the Internet in the first place.

“Today, Internet access is as basic as electricity and water connectivity in this country – as roads, as transportation,” said Maria Smith, an affiliate of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University. Her documentary about Internet access inequities in the United States, “Dividing Lines,” came out this year.

While producing the film, Smith said she found disparities in Internet access everywhere she looked – and Cambridge was no exception.

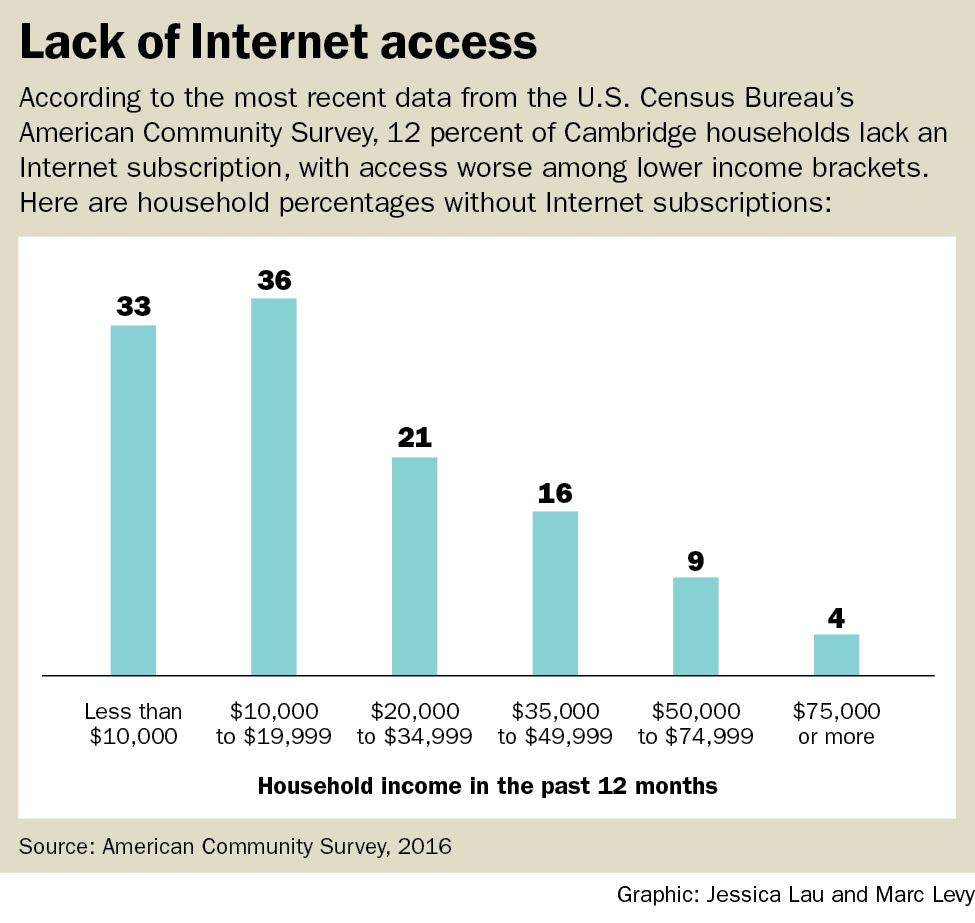

According to the most recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, 12 percent of Cambridge households do not have an Internet subscription. Lack of Internet access is more severe for lower-income brackets: 21 percent for households with incomes of $20,000 to $34,999; 36 percent for $10,000 to $19,999; and 33 percent for under $10,000.

For residents unable to access Internet at home, options are scarce. Smith said that students might have to “go stand in line at the library to apply for college.” The Cambridge Public Library has limited evening hours at some branches, and patrons have a daily quota of two hours of computer access. (The library website continues to post an outdated 2013 policy that allows a single hour of computer use each day.)

Addressing a lack of choice

In some cases, lack of Internet access is a matter of not being able to afford the service. Additionally, Smith said that many areas nationwide do not have the physical infrastructure for Internet connection. Internet service providers explain the situation using economics-based arguments, she said: Running cables to low-income areas is not profitable, or consumer demand in those areas is not high enough.

“The word ‘consumer’ implies that you have an active choice,” Smith said. “In a lot of these scenarios, you don’t really have a choice.”

Colin Rhinesmith, an assistant professor in the School of Library and Information Science at Simmons College, said that the Comcast monopoly on providing Internet service in Cambridge is a failure of the market economy. “There is an argument for the government to step in, to make sure that everybody has access,” he said.

Rhinesmith was referring to municipal broadband: high-speed Internet service provided by city or town government.

Municipal broadband is a significant investment that requires strong public support. In 2009, Concord launched a $3.9 million project to outfit the town with a network of fiber-optic cables capable of transmitting high-speed Internet. The town started to offer Internet service in 2015.

The initiative met Concord’s goal of providing homes and businesses with quality Internet access. With service available to 95 percent of the town, Concord broadband offers higher data upload speeds than its competitor Comcast and upholds a policy of net neutrality.

In Cambridge, the conversation about building a municipal broadband network is progressing slowly. In 2016, the city’s Broadband Task Force recommended that Cambridge conduct a feasibility study to assess whether a municipal broadband system would be economically successful. But to this day, the city manager has not announced next steps.

Booting up help

Colin Rhinesmith leads a discussion about Internet access during a June 21 event hosted by Upgrade Cambridge. (Photo: Jessica Lau)

A grassroots organization called Upgrade Cambridge formed in March to raise awareness of how municipal broadband can help Cambridge. But even if successful at building enough public support to pressure the city into action, it would take years to put funding and infrastructure in place.

While municipal broadband may be a viable long-term strategy to improve Internet access in Cambridge, Rhinesmith said that people need access now. To develop more immediate solutions, he works with public libraries and community-based organizations.

“I’m looking at how public libraries – right now it’s the Boston Public Library – can lend hot spot devices to help people who can’t afford to access the Internet,” he said.

Portable hot spot devices connect to local cell towers and put out a wireless Internet signal. The Boston Public Library is preparing a pilot program that would let low-income residents borrow the devices just like books.

Rhinesmith said that creative initiatives such as this one are crucial to closing the Internet access gap. He said that whatever strategy Cambridge may take, it is necessary “to partner with local existing community-based organizations that are trusted in low-income neighborhoods” to best serve their needs.

One such organization is the nonprofit Tech Goes Home, which helps low-income people get Internet access at home, learn digital skills and buy computers. While based primarily in Boston, the organization is expanding efforts in Cambridge, said co-executive director Theodora Hanna.

Carl Baty runs digital literacy courses for the nonprofit, teaching in and out of the classroom. “It’s no sense having something they can’t use. If something’s wrong, call me,” he said, explaining trips he makes to students’ homes to help troubleshoot Internet and computer issues.

Baty has seen firsthand how Internet access improves people’s lives. “They’re shopping online and they’re paying parking tickets,” he said about his students. “Every time I would go by there, the last couple classes, they had something new to tell me they’d done.”

Watkins is just one of many Cambridge residents demanding better Internet access for their city, home to a high density of top universities and cutting-edge technology companies as well as frequent boasts of innovation. The library system, for instance, notes that in 1994 it became the first library in the world to offer free high-speed Internet access and still offers more than 100,000 hours of free access annually on more than 50 computers to those who need it – for two hours a day.

“It seems like being in Cambridge, with all the technology, we should have more ways to do it,” Watkins said.

Jessica Lau is a journalism student at Harvard University.

Don’t forget the lousy Verizon DSL some of us have “access” to.