Remembering Peter: Not from our city, maybe, but the courageous Rev. Gomes was surely of it

The Rev. Peter Gomes delivers a sermon Oct. 31, 2010, seen in a screen capture from a video taken at the Duke University Chapel in Durham, North Carolina.

Peter’s mother’s family, the Whites, and my mother’s family, the Wrights, had known each other for decades as part of Cambridge’s vibrant Black community. In the 1940s, they lived doors from each other on Concord Avenue. It is here that my mother, Lovette Wright, and Peter’s cousin, Marjorie White, formed a lasting friendship. Sometime during their teenage years, Marjorie moved to Plymouth with her aunt Orissa, who had gotten married. Orissa gave birth to Peter in 1942.

I knew Peter only as a boy; on the anniversary of his death Feb. 28, 2011, I now marvel at the man he became.

The Rev. Peter J. Gomes, Plummer professor of Christian morals at Harvard Divinity School and Pusey minister at Memorial Church, spent 40 years in Cambridge, his mother’s city, in service to uplifting humanity. To those who knew him, he was irresistibly compelling, with a wit, flair and panache that made him unforgettable. Singular in manner, he would describe himself eloquently as a Black, gay, Yankee, Republican, Bates- and Harvard-educated preacher. He was a one-man lesson in diversity.

In his 68 years on the planet, he wrote more than a dozen books, including bestsellers, accumulated more than 39 honorary degrees, and participated in the inaugurations of presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. His honors and accomplishments are too numerous to mention. My favorites were that he was named to the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St. John, the oldest order of chivalry in Britain, and that he met and conversed with Queen Elizabeth II. As boys, Peter and I talked about the Knights of the Round Table, so I can only imagine his delight in receiving those honors. Proclaimed by many for his scholarship, he was a teacher, mentor and a source of inspiration to many. I would like to remember him for his courage and nobility of spirit, for I reflect upon the following examples of speaking truth to power to make my point.

In 1991, a conservative student journal at Harvard called Peninsula had published a 56-page critique of homosexuality and gay activism. There was a protest rally in Harvard Yard made up of students, faculty and administrators. Members of Peninsula were there as well. From the steps of Memorial Church, Peter declared that he was gay. According to Mary Jordan in The Washington Post:

“First a gasp of astonishment. Then cheering so loud that he could no longer be heard. The student protesters jumped up and down, hugged each other, tossed their hats in the air. They looked like the winning team after the World Series.”

In 2008, he came to the defense of embattled Black preacher Jeremiah Wright, pastor to Barack Obama, who declared from the pulpit in colorful language that America justly deserves God’s wrath for its racial crimes. As Obama distanced himself from his pastor, Peter bravely weighed into the political maelstrom. When asked about Wright’s anger, he responded by saying,

“Wouldn’t you be unhappy? Don’t you remember what your people did to our people? Have you forgotten that? He hasn’t.”

In 1992, this revered clergyman, whom Time magazine in 1979 called “one of America’s seven greatest preachers,” took on religious fundamentalism in an essay for The New York Times:

“Religious fundamentalism is dangerous because it cannot accept ambiguity and diversity and is therefore inherently intolerant. Such intolerance, in the name of virtue, is ruthless and uses political power to destroy what it cannot convert.”

Even as a boy, Peter could teach. my mother would bribe me to travel to Plymouth from Cambridge to visit Marjorie with the promise of fried clams and ice cream. It worked every time. Peter was always there. He was a few years older and a different type of playmate from those I was used to. He did not like to play ball or games. Instead, we talked, he read to me and told me stories. He told me about Plymouth and its Native American history.

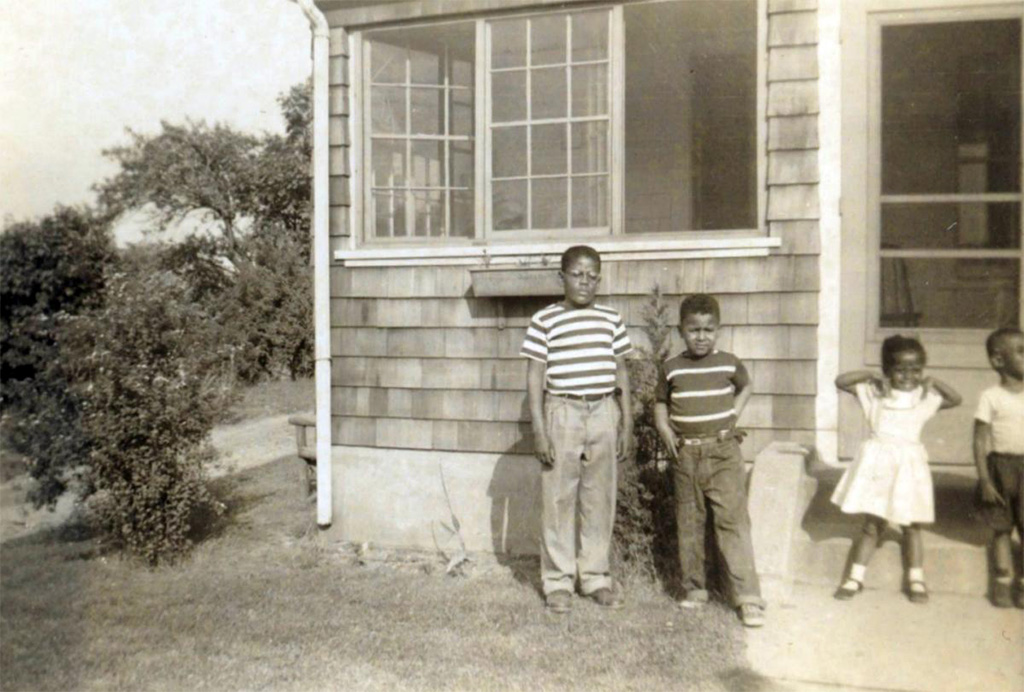

The Rev. Peter Gomes, center, at age 10 in Plymouth. The author, James Spencer, is at right at age 6.

I remember Marjorie and my mother taking us into town and Peter showing me Plymouth Rock and telling me the story of the Mayflower, the pilgrims and the indigenous people who had showed great humanity to the desperate English immigrants.

Peter and I would walk through the town side by side, with Marjorie and my mother behind us, and he would point things out to me like he was conducting a tour or teaching a class. We must have been quite a sight back there in the early 1950s, two young Black boys stopping and taking note of all the historical aspects of that wonderful city that Peter loved so much.

As we grew older, I lost touch with Peter but would get periodic updates from Marjorie, my mother, and my sister. On more than one occasion, I was invited to one of his soirees only to be a no-show, something I now truly regret.

Although Peter was not from our city he was of our city. I hope we never forget him.

Below is a picture of Peter and me in front of his Plymouth home circa 1954. I was 6 and he was 10. As you can see, I have three stripes and Peter, being older, had a great many more. My younger cousins Donna and Bruce are also in the picture.

It is unnerving to see a picture in which you are the only one still alive:

Marjorie White, Peter and my mother, Lovette Spencer:

James Spencer is president of The Cambridge Black History Project.