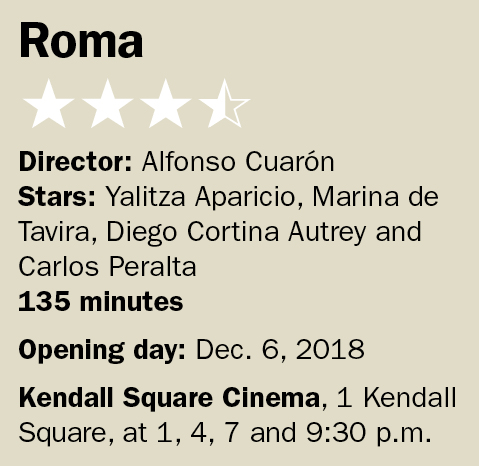

‘Roma’: Calling on the maid to be a mother when chaos strikes a family and ’70s Mexico

Alfonso Cuarón, the Mexican-born director who’s made a reputation of tackling a wide variety of subjects and milieus, hopping from the depths of outer space (“Gravity”) to barren, post-apocalyptic futures (“Children of Men”) and even Harry Potter and Dickens (“Prisoner of Azkaban” and “Great Expectations”), returns to his homeland – where be crafted his signature tale of taboo sex and betrayal, “Y Tu Mamá También” – to forge the semi-autobiographical contemplation “Roma,” something of a nostalgic dream cut with historical incident and unhappy reality. Folks who could never bite into the floaty neorealism of Fellini’s “8½” or “Amarcord” will struggle with the director’s languid sense of place and time, hoping for more of the disruptive chaos of the earthquake, wildfire and class revolt that punctuate the film. The central dilemma of a pregnant housemaid abused and abandoned by her lover and trapped by her unenviable station in life might not jump off the page, but for those who give it time, there are rewards.

The time is the early ’70s (aptly Fellini-esque) in Mexico City, as the camera swirls around the doings of an upper-middle-class family. Dad (Fernando Grediaga), a doctor, works long hours at the hospital while mom (Marina de Tavira) and the housemaid, Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio) maintain the homestead and look after a brood of corrigible youth. Mom and Cleo care, but are not the most effective homemakers. Mom dings up the car every time she takes it out and Cleo allows mounds of canine fecal matter to amass in the driveway – cars skid and people slip on poo, it’s a running thing. The film’s driving factors are the father’s sudden and prolonged absence as well as Cleo’s pregnancy: How she gets pregnant, the father’s reaction and the end result of which provide for surprising turns.

The time is the early ’70s (aptly Fellini-esque) in Mexico City, as the camera swirls around the doings of an upper-middle-class family. Dad (Fernando Grediaga), a doctor, works long hours at the hospital while mom (Marina de Tavira) and the housemaid, Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio) maintain the homestead and look after a brood of corrigible youth. Mom and Cleo care, but are not the most effective homemakers. Mom dings up the car every time she takes it out and Cleo allows mounds of canine fecal matter to amass in the driveway – cars skid and people slip on poo, it’s a running thing. The film’s driving factors are the father’s sudden and prolonged absence as well as Cleo’s pregnancy: How she gets pregnant, the father’s reaction and the end result of which provide for surprising turns.

“Roma” moves in subtle, wispy ebbs fueled by undercurrents of class and gender oppression. There’s a poignant yin and yang in every frame. Fate and circumstance factor large too as the action moves from the cloistered streets of the city to the bourgeois countryside, even a muddy hillside slum and ultimately a riot (the Corpus Christi Massacre of 1970). Throughout it all Cleo and Sofia rally frantically to keep the children safe, despite considerable setbacks. “Roma” is clearly a love letter to the women who made Cuarón the person he is today.

The film, shot by Cuarón himself in black and white – an artistic high-dive against the grain but in good company (think “Schindler’s List,” “The White Ribbon” and “The Artist”) – is a scrumptious wonderment to behold. If there’s any subversion, it’s that “Cold War,” another foreign language film in a similar format yet radically different style, could give Cuarón a run in the best-cinematography category.

Artistic merits aside, the key to “Roma” is the patiently quiet and soulful performance by Aparicio. Clea’s fleeting optimism amid repressed pain amid continual reminders of her subservient role are heartwarming and heartbreaking. You want her to break out and do something bold, but in her quiet resolve there’s a deeper dignity that transcends.“Roma” is not about good or bad, but about connecting and persevering.

Tom Meek is a writer living in Cambridge. His reviews, essays, short stories and articles have appeared in the WBUR ARTery, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, The Rumpus, The Charleston City Paper and SLAB literary journal. Tom is also a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics and rides his bike everywhere.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks