Jump seen in child porn and domestic violence since start of coronavirus lockdown, police say (updated)

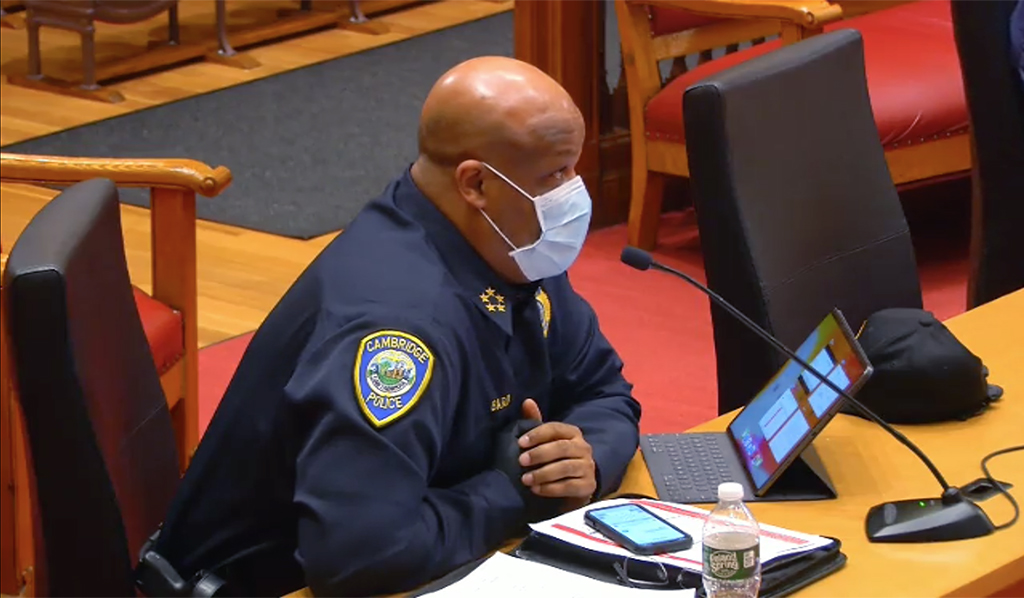

Police commissioner Branville G. Bard Jr. reports Monday to City Councillors.

Police have seen a surge in domestic violence and child pornography cases since the beginning of the coronavirus lockdown several weeks ago, police commissioner Branville G. Bard Jr. said Monday.

“We’ve seen a marked increase in child pornography cases. In the last eight weeks, we’ve seen what we typically see in six months worth of cases,” Bard told city councillors at their regular meeting.

It was unclear how police had learned of the incidents and what Bard’s statements meant in terms of arrests and charges filed. A police spokesman said there would be more information Tuesday, but then reported that, “due to the sensitive nature of these investigations, no further data or information is currently available.”

And Bard later clarified that his remarks about the rise in child pornography was “not necessarily [meant to make] a causal link to the shelter in place” order that had kept people in their homes since at least March 16, the day students began remote learning and municipal buildings, libraries and playgrounds closed.

“The fact is, we have seen an alarming increase over the last eight weeks, [but] I wasn’t directly linking it to the shelter in place,” Bard said. “There may be some correlation.”

In fact, law enforcement around the globe have reported on surges from India to the Philippines, which hosts “on-demand, child sexual abuse and exploitation that is being livestreamed from traffickers in the Philippines to child sex offenders around the world, primarily in Western countries,” NPR was told last month by John Tanagho, the field office director for the International Justice Mission in that nation. A recent report out of India showed that it wasn’t just a jump in demand for child sex keywords on porn sites, but that demand for extremely violent child pornography had grown by 200 percent since a Covid-19 lockdown began there March 23.

One thing that makes children vulnerable: As they “spend more time online during the lockdown, they are often unsupervised,” the report says.

Layoffs play a role in a different kind of abuse in which parents exploit their children, a Cambodian children’s charity told NPR, as “people sometimes go through desperate measures because they’re hungry.”

None of this necessarily relates to Cambridge’s cases, but the city wouldn’t be alone in seeing a spike in crimes against children.

Domestic violence

Similarly, a spike in domestic violence has been seen worldwide and is predicted whenever families are forced together, and particularly when the abused have no place to escape to, experts have said.

In Cambridge, “we saw increases both in terms of the amount of calls and in terms of the nature of the seriousness of the calls,” Bard told councillors.

In the seven weeks preceding the shelter-in-place order, there were 74 incidents of domestic violence; during the first seven weeks of the order, that rose by 28 percent, to 95 incidents. As the lockdown went on from March to April, there was a 19 percent increase, Bard said. The figures are “particularly disturbing because we know that there’s a ‘dark number’ as it pertains to domestic violence, meaning we know that there are a number of domestic violent crimes that occur but go unreported, and that that number should go up during a time like when there’s a shelter-in-place order in effect.”

Although reported domestic cases – not all of which are intimate partner violence – were up compared with 2019, they were nearly even with 2018, noted Jeremy Warnick, director of communications and media relations for Cambridge police.

For instance, there have been 10 cases of aggravated assault, far over the three reported from this period last year, but not far over the eight from 2018; the 72 domestic disputes are far over the 58 from last year, but match the numbers from 2018; and simple assaults are down – from 26 last and year and from the 23 reported two years ago, Warnick said.

“We have victim advocates who work closely with local domestic violence service providers, and in select cases victims are removed and housed by those local partners,” he said. Those resources were outlined early in April.