Clearwing moths are a rare daytime species, pollinating among your garden honeysuckle

A pin oak clearwing moth in Devens on July 3. (Photo: Tom Murray)

Bees hog all the credit for pollinating our flowering plants, but did you know that moths pollinate about

40 percent of them? In fact, moths pollinate some types of flowers that bees do not even visit! Moths fly from flower to flower feeding on nectar at night, much like bees do during the day.

Moths evolved long before butterflies, which may explain why there are about 10 times as many species of moths as there are species of butterflies: at least 160,000, although some experts think there may be as many as half a million. Since many moths feed on flowering plants, it is believed that they co-evolved with them.

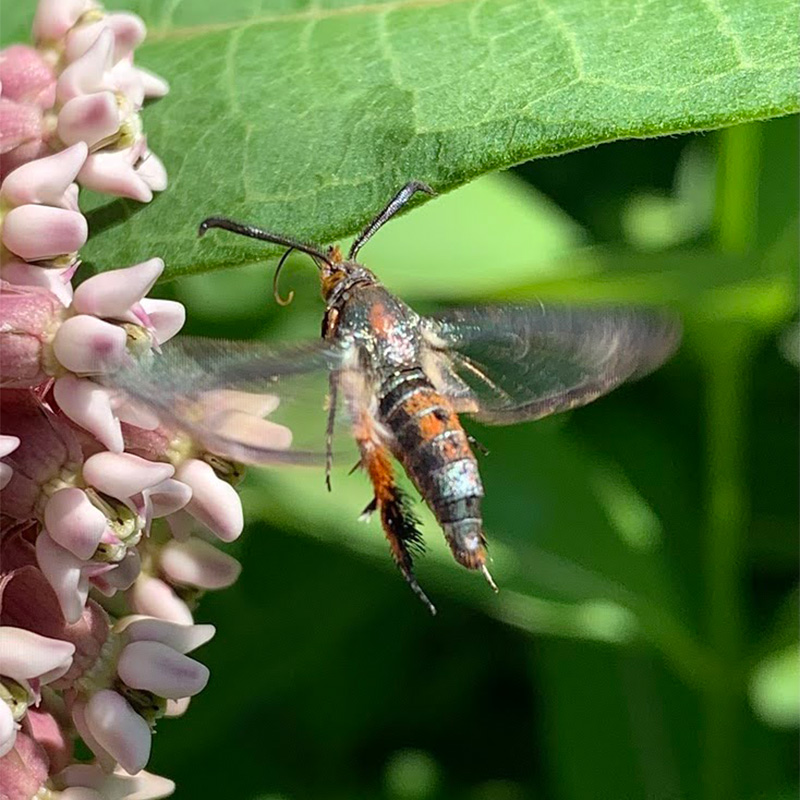

A maple clearwing moth in Pelham on Aug. 6. (Photo: Tom Murray)

Most species are unidentified, largely because most moths are nocturnal and harder to study than daytime animals – though there are species active during the day, which is why you may have encountered clearwings, which have sections of their wings that do not have scales and look transparent. Clearwing moths often resemble other flying insects, such as bees, hornets, wasps or hummingbirds.

You might spot one in a meadow, the edge of a forest or even in your garden. Look for them on bergamot plants (also known as bee balm), honeysuckle, verbena or phlox. They drink flower nectar by dipping their long proboscis into the flower and sucking up the nectar like drinking through a straw. They can find nectar hidden deep in tubular flowers because their proboscis can be as long as their body!

A peachtree borer moth in Dedham on March 27, 2020. (Photo: Jef C Taylor)

Moths do not have noses, but use chemical receptors in their feathery antennae to grab molecules in the air. The feathering increases the surface area and make moths extremely sensitive to smells. Clearwing moth females produce sex-attractant pheromones from glands at the tip of their abdomen. The pheromones attract males. Some moths can sense these pheromones from many miles away.

After mating, the female lays tiny green eggs (no ham) on the underside of leaves that the caterpillars can eat. The eggs hatch into caterpillars (most of which have a spiky tail and are sometimes called horn worms). The caterpillars munch on honeysuckles, blueberries, cherry, plum, cranberry and members of the rose family. Once they are completely grown, the caterpillars plummet to the ground. There they spin a thin-walled cocoon in leaf litter, where they lie dormant throughout the winter. In late spring, they emerge as adults with fully grown wings, visiting and pollinating flowering plants – one more reason to leave leaf litter alone until spring: Clearwing moths may be overwintering in it.

A snowberry clearwing moth in Groton on July 24, 2021. (Photo: Tom Murray)

We all know that butterflies migrate, but did you know that moths migrate, too? Of course, being moths, they do it at night, so we do not see them. Moths may migrate to find a better food supply or to avoid hot, dry weather. Scientists who investigate these things assumed that high winds would throw migrating moths off course, but this does not happen – moths continue straight on their path no matter the strength or direction of the wind. When the wind blows in their faces, moths increase their speed while flying low to the ground. When the wind blows at their backs, moths fly up high, slow down and let the wind push them.

We all know that moths are attracted to porch lights, but the reason for this is not well understood. Some research indicates that to fly in a straight line, moths maintain a constant angular relationship with the moon or stars. Light bulbs interfere with their ability to maintain this relationship, and the moths end up flying toward the artificial light instead.

A squash vine borer moth at Spot Pond in Stoneham on July 8. (Photo: Bill MacIndewar)

Some moths are agricultural pests, and others eat our wool clothes or infest our pantries. Most are beneficial, though. In some places, emperor moth caterpillars are an important food source, providing protein, fat, vitamins and minerals. In the Congo, for example, more than 30 species of moth caterpillars are harvested, dried and sold in local markets or shipped by the ton to other nations. Processing plants in Botswana and South Africa package dried moth caterpillars to be sold in stores and cooked at home. Caterpillars are easy to raise, fast-growing and a potential food source around the world.

NASA is launching high-resolution satellites in 2028 to study climate change. These satellites will be able to evaluate the health of forests, map coral species, track greenhouse gases, monitor heat of wildfires, track warming ocean current, pinpoint urban heat islands and much more, including tracking moths, butterflies and dragonflies as they fly all over the world.

Moths have many predators, including this frog seen in July 2020. (Photo: Tom Murray)

Moths have many predators, including bats, owls, birds, reptiles, amphibians and even bears. Humans are their greatest foe, though. Moth populations have declined severely since the 1970s due to pesticide use, light pollution and lack of plant diversity. These declines in moth populations indicate a crucial need to protect these valuable pollinators before it is too late. Even though moths are often out of sight, they should not be out of mind.

![]()

Reader photo

Deb Davis spotted this indigo bunting in Petersburg, Kentucky, on July 10.![]()

Have you taken photos of our urban wild things? Send your images to Cambridge Day, and we may use them as part of a future feature. Include the photographer’s name and the general location where the photo was taken.

Jeanine Farley is an educational writer who has lived in the Boston area for more than 30 years. She enjoys taking photos of our urban wild things.

Wonderful photos!