Public housing revamp falters midway, with thousands of units deteriorating

The redevelopment of Jefferson Park housing in North Cambridge is one of the renovation projects underway at the Cambridge Housing Authority.

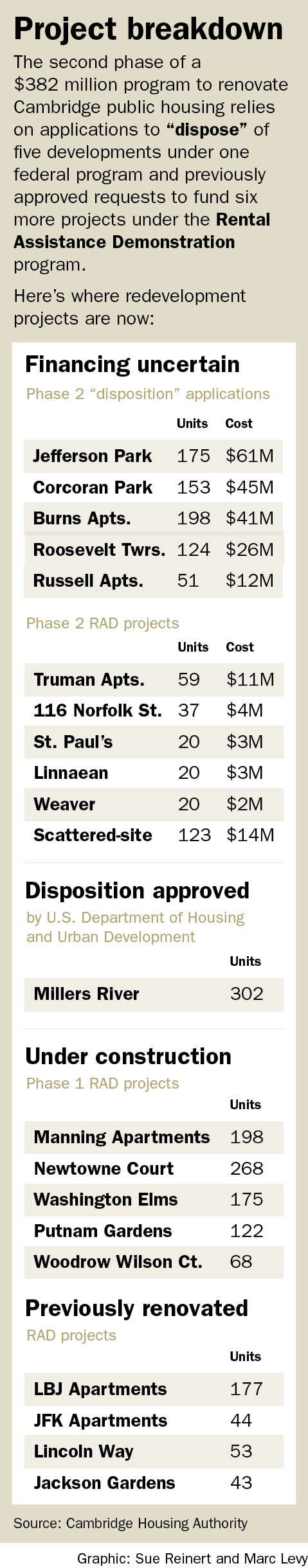

Funding for the second phase of a $382 million program to renovate thousands of units of city public housing is uncertain, and construction may not begin until 2019. The unexpected holdup, caused mainly by state funding problems, unforeseen levels of deterioration and rising construction costs, hasn’t affected ongoing work on the first phase of the huge project.

A more ominous but also more speculative problem involves low-income housing tax credits, a mainstay of the financing package; private investors buy tax credits by investing in low-income housing, no repayment required. Uncertainty over President-elect Donald Trump’s promise to cut the corporate income tax has made the tax credits less attractive, Cambridge Housing Authority planning and development director Margaret Moran said at an agency board meeting Dec. 14.

A more ominous but also more speculative problem involves low-income housing tax credits, a mainstay of the financing package; private investors buy tax credits by investing in low-income housing, no repayment required. Uncertainty over President-elect Donald Trump’s promise to cut the corporate income tax has made the tax credits less attractive, Cambridge Housing Authority planning and development director Margaret Moran said at an agency board meeting Dec. 14.

“The 4 percent tax credit program is at risk,” she said. “Investors have slowed or limited their offers because of uncertainly about the corporate tax rate.”

Responding to the some of the problems, Cambridge Housing Authority has hurriedly applied to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to finance five of the most dilapidated Phase 2 developments – returning to a program federal officials barred Cambridge from using four years ago.

To sidestep a shortage of state bonds, the Cambridge agency is also considering issuing its own bonds or having the city issue bonds for Phase 2.

Despite the problems, Moran says the project will be completed. “I feel very confident that a path forward will be found,” Moran said in a November interview.

Decade of effort

The authority has been working since 2006 to redevelop the city’s 2,130 public housing units, an increasing scarce resource for low-income families and individuals as rents skyrocket. Agency officials have said it’s vital to modernize the developments before they deteriorate to the point where people can’t live in them, but the task became more daunting as federal support for public housing dwindled.

In its earliest attempt to modernize developments, the agency tapped funds from the federal stimulus program in 2010 to renovate four developments: LBJ Apartments, JFK Apartments, Lincoln Way and Jackson Gardens.

In 2012, planners tried to use a loophole in federal rules to rehabilitate the remaining projects that needed work. The strategy called for “disposing” of the public housing units by transferring them to nonprofit corporations controlled by the CHA. The loophole would have allowed the developments to collect as much as twice the public housing allowance from HUD; that income would have supported loans and allowed private investments for construction.

As public housing agencies around the country tried to take advantage of the loophole, HUD closed the opportunity shortly before the Cambridge application was filed.

Then the federal agency opened another door. It changed the rules for its Rental Assistance Demonstration program to allow use by high-performance agencies such as Cambridge’s. In December 2013 the federal agency approved Cambridge’s application to redevelop the rest of its public housing that needed work under RAD. It also approved rebuilding one of the most deteriorated developments, Millers River, under the disposition program, because RAD would not provide as much financing as the project needed.

Big demand statewide

Both programs, RAD and disposition, will essentially eliminate public housing because they require the Cambridge agency to transfer its holdings, on paper, to private entities. It will continue to manage the developments, though, and has promised that most tenant protections won’t change and that the housing will remain low-income through measures such as deed restrictions and because the agency will continue to own the land on which the developments sit.

The first phase of RAD, for about $150 million in construction at five developments, began in early 2014 and is proceeding. But the agency had to stagger funding for one development, Manning Apartments, when the state unexpectedly didn’t have enough bonding authority to cover the whole project at once. It was the first sign of a problem that now affects the program’s Phase 2.

Moran said there is so much demand in Massachusetts for “private activity bonds” – those sponsored by private developers such as schools and the entities that now own the agency’s developments – that the state can no longer carry over unused bonding authority from one year to the next. The state typically allocates about $200 million in private activity bonds to multifamily housing, she said, and “even if we stagger” bond needs, Cambridge’s Phase 2 program alone would need $50 million to $100 million a year starting in 2017.

Private activity bonds for multifamily housing are even more important because they trigger allocation of low-income housing tax credits to a project, Moran said.

Problems mount

Even if the Cambridge agency solves the bonding problem, it will have to persuade HUD to approve rebuilding five more developments besides Millers River under the disposition program – a program that requires the federal government to put much more money into low-income housing than the RAD program does.

The authority’s board of commissioners approved the five disposition applications one after the other, without discussion, at its December meeting. In addition to newly discovered problems at the five sites, construction costs have climbed, Moran said.

Asked what the chances are for federal approval of the disposition applications, Moran said the consultant hired by CHA to advise it on funding Phase 2 has said federal officials are giving the go-ahead to disposition projects requested by other public housing agencies, and the federal agency is acting more quickly than usual.

But Moran also told the commissioners that “the backup plan” if bonding and other funding mechanisms aren’t enough to pay for the entire Phase 2 program “will always be doing less.”

Take from Peter to pay Paul

In another uncertainty, agency officials have not said what they will do if HUD approves the disposition requests but doesn’t approve enough new rent subsidies – the vehicle bringing in income and making sure low-income families can keep affording the rent – to cover all the units.

Several years ago the agency said that if necessary, it might take a limited number of rent vouchers from the rent subsidy program that lets tenants rent from private landlords and add them to the RAD program, which ties the subsidies to the apartments in RAD. That might reduce the number of subsidies available to lower-income people who don’t live in public housing.

One comment on the latest plan to ask federal approval for disposition of the five properties asked what would happen if the Cambridge agency didn’t get enough new rent vouchers to cover the disposed buildings. The response: “We would have to figure out our response at the time.”