Finding Mr. Gilbert: Yet another remarkable Black Cantabrigian hiding in plain sight

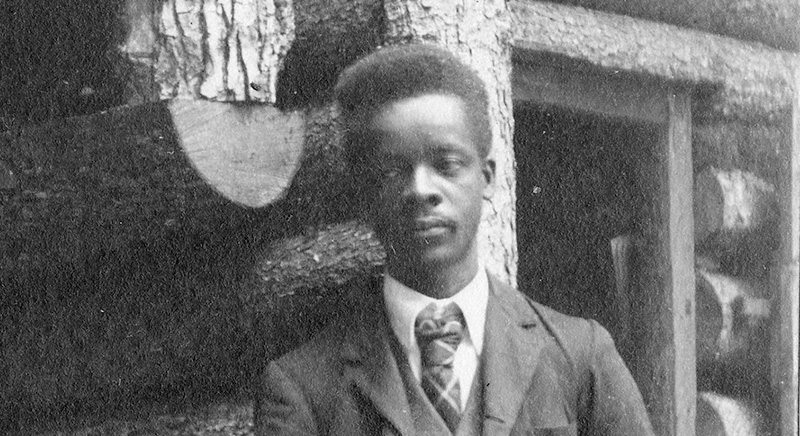

Robert Gilbert, right, with a group at a cabin. This is the only known photo of Gilbert. (Photo: Mass Audubon)

John Hanson Mitchell was “Looking for Mr. Gilbert” and used that title for his wonderful book about his decadeslong search. It turned out Robert Alexander Gilbert was hiding in plain sight in Black Inman Square, home to my family for generations.

When most people think of the historical Black Cambridge neighborhoods, they think of The Port, “The Coast” and North Cambridge. (We called it North Cambridge despite it being West Cambridge, and the name just stuck.)

Inman Square had a lesser concentration of Black-owned homes. But this area had housed some of the most prominent members of Cambridge’s Black intelligentsia in the early 20th century. My uncle and aunt Clement G. and Gertrude Wright Morgan were leaders of the Niagara Movement and instrumental in founding the NAACP. They held activist meetings, fundraisers and socials at 265 Prospect St., where they lived from 1898 until Uncle Clem’s death in 1929. They also housed Black Harvard students, as did many other Black homeowners in Cambridge. Maria Baldwin lived at 196 Prospect St. from 1892 until 1905 and sponsored all types of gatherings for the Black community. The parents of G. David Houston (1880-1940), a professor of English at Howard University and the first Cambridge-born Black student to attend Harvard College, lived at 105 Inman St. from 1901 through the 1920s. Other solidly middle-class Black families – the Ashes and Plummers, Freemans, Lawrences and Colemans among them – lived up and down Inman Street in those decades.

Robert Gilbert, their neighbor at 66 Inman St. from 1915 until his death in 1942, was a quiet but no less impressive community member. Although Mitchell’s book was published nearly 20 years ago, the story of Gilbert – ornithologist, photographer, musician, chef, entrepreneur, churchman – has new resonance for me. This is because the Cambridge Black History Project and our community in general now increasingly understand our history as a continuous web of intertwined relationships and cooperative connections reaching back to at least the 1700s, not simply a collection of a few “exceptional” individuals.

Mitchell was researching a book on New England landscape photography when he uncovered a trove of about 2,000 photographic glass plates credited to the ornithologist William Brewster (1851-1919), who had been the curator of mammals and birds at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology and first president of Mass Audubon. This chance encounter followed by painstaking archival research (in the days before digitization) led to verification that most, if not all, of these photographs had been taken by Gilbert, not Brewster.

Gilbert was well-known in the Black community and at Harvard, which meant also in the “Boston Brahmin” community. He was born in 1870 in Virginia and had come north as a teenager. He answered an ad and was hired as an assistant to Dr. A.P. Chadbourne at the Harvard Medical School, working with the lab animals. In the 1890s, Chadbourne recommended him to Brewster.

Author Mitchell found Gilbert to be a polymath, an accomplished musician, entrepreneur, ornithologist and world-class photographer. Mitchell further discovered that Gilbert had lived in France and Sweden and was proficient in their languages. He even conjectures that Gilbert was the inspiration for F. Scott Fitzgerald’s character Jules Peterson in “Tender is the Night”: a Black man who has failed as a small manufacturer of shoe polish in Stockholm, a story identical to Gilbert’s entrepreneurial endeavors.

Coming from a family that has lived in Cambridge and traveled around New England for six generations, I’ve heard plenty of stories. So I know Gilbert was often navigating potentially dangerous waters for a Black man. He was, in the words of one obituary, Brewster’s “Man Friday,” and no matter how highly Brewster respected Gilbert and how little Brewster seemed to care about color, we get what that meant to the white community – indispensable but unequal. Brewster curated a private museum at his home on Brattle Street as well as the collection at Harvard’s MCZ and would travel frequently all over New England to study birds in the wild. In addition to tending the museum collections, Gilbert assisted on these trips, driving Brewster’s Model T and handling the camera, all the equipment and provisions. But Brewster at times required Gilbert to take the car solo on errands far afield from Cambridge.

At this time, New England was not exactly welcoming to Black people. Decades after Gilbert’s trips into the countryside, Blacks were still being hassled constantly; many relied on the Green Book to try to make their way safely through the region. Realtors would not show homes to Blacks in white neighborhoods. Bill Russell, star of the Boston Celtics in the 1950s and ’60s, was harassed constantly, his home in Reading broken into and vandalized in the vilest ways. Stories like this abound. In 1965, my family found a house to buy in Lexington and people in that community signed a petition to keep us out. There was a meeting at a local school where it was said that the 18-year-old boy (me) would rape their daughters. Mitchell recounts a scary run-in Gilbert had with Arlington police, and I doubt this was an isolated incident. I can only imagine the courage and savvy it took for Gilbert to navigate and survive his New England tours.

When Brewster died in 1919, Gilbert was hired by the MCZ – the first Black employee at the institution founded by Louis Agassiz, a scientific racist who found Black people repulsive. (In light of this fact, our Agassiz School, where Maria Baldwin was headmaster, has been renamed for her.) Gilbert prepared and maintained the taxidermy and other exhibits. Although this appears to have been a secure job in a field that held a great deal of interest for Gilbert, it couldn’t have equaled the adventures he had had with Brewster and so may have seemed a step down. Also, his only son, Robert Jr., had died suddenly in 1915, and his wife, Anna Scott Gilbert, in 1919, not long before Brewster. Gilbert had three teenage daughters to raise. Maybe he felt he needed to change his direction and regain more autonomy.

Perhaps that had something to do with why he went to Sweden and France in the 1920s to try to sell the shoe polish he had developed. Or maybe he had heard from returning soldiers in the neighborhood how respectfully they had been treated in France. War hero Clifton Merriman and my grandfather Bruce Wright, the only Black soldier to have his war diary published, lived in the Inman Square neighborhood, Merriman on Tremont Street and my grandfather with the Morgans on Prospect. They had fought with the 372nd U.S. Infantry, a segregated unit that refused to do menial duties for the American Army and chose instead to fight under French Army command. In France they were considered heroes and were highly decorated. I’m sure the stories in their letters home circulated in the community. After the war, they worked tirelessly to uplift the Cambridge Black community, later from the VFW Isaac W. Taylor post, which took up residence in the Inman Square firehouse in 1932.

The shoe polish venture didn’t pan out, and Gilbert returned to Cambridge. Back at the MCZ, he became the chef for the museum’s famous, exotic Eateria. Created by museum director Thomas Barbour, it became the go-to dining spot of Harvard president A. Lawrence Lowell (who was unlikely to recognize Gilbert’s value beyond his cooking), as well as of visiting dignitaries and biologists from across the globe. This lunchroom’s unique fare included Chinese frog stew with diced pig ears and white grubs, sweetmeats of bush babies, exotic snails and other delicacies. The Eateria’s most famous entrée, Elephant Foot Stew, was a specialty of Gilbert’s, whom I suspect saw this as just cooking a big pig’s foot. I imagine that Gilbert brought the competencies learned from our African ancestors to bear to create at Harvard, of all places, perhaps the only soul food restaurant most of these visitors ever ate in. Our people have always been able to turn the most unpopular parts of any animal into delicious dishes.

For the next decade or so before his death, in addition to his work at the MCZ, Gilbert led a steady life as a respected member of the community – he sent his daughters to college, served as a deacon at St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church, gave piano lessons.

Like most of his and my Black neighbors, Gilbert was constantly crossing the boundary from white America to Black America, from Harvard’s campus to Inman Square, from the MCZ to St. Bartholomew’s. In the Cambridge tradition of Charles Lenox and Francis Prince Clary and who knows how many others, he was a most remarkable man hiding in plain sight. Mitchell’s fascinating book illuminates the bewildering obliviousness that Gilbert’s white counterparts possessed so as not to notice his genius. Unfortunately, his experience is not so unusual, even today.

![]()

About the Cambridge Black History Project

The Cambridge Black History Project is an all-volunteer organization of individuals having deep roots in Cambridge. We are committed to researching, accurately documenting, preserving and illuminating the journeys, accomplishments and challenges of Black Cantabrigians, and to raising awareness of their stories through educational outreach to the Cambridge community and beyond.

The Cambridge Black History Project is an all-volunteer organization of individuals having deep roots in Cambridge. We are committed to researching, accurately documenting, preserving and illuminating the journeys, accomplishments and challenges of Black Cantabrigians, and to raising awareness of their stories through educational outreach to the Cambridge community and beyond.

Special thanks for research help to Charles Sullivan and the staff at the Cambridge Historical Commission and Alyssa Pacy at the Cambridge Public Library Cambridge Room.

Thank you Jim. You’re a treasure trove and a remarkable historian and Cambridge cheerleader. Your stories about Black Baseball history floored me. Keep writing please .

James, Thank you.

If he (and many others) could not have the respect due them in his lifetime, you have at least rendered Gilbert’s brilliance for us to see and read about in awe today.