Cleanup at 12 Arnold Circle was halted quickly for slapdash handling of lead without license (updated)

A state inspection report says cleanup at 12 Arnold Circle hasn’t followed guidelines on lead removal. (Photo: Sue Reinert)

Workers had finally begun cleaning up the deteriorating apartment building at the center of a long-running legal fight when the state suddenly ordered work stopped in August because of lead paint removal violations. Renovation of 12 Arnold Circle had stalled for years while court battles continued over the building’s dangerous condition and, later, the city’s inclusionary housing ordinance.

The stop-work order came Aug. 30, a little more than a month after developer Edward Doherty bought the four-story, 12-unit building and he obtained an interior demolition permit. Doherty had promised to move quickly to make the property safer, especially for neighbors in the crowded cul-de-sac, who had watched the building decay for years.

Then work remained at a standstill for another month, until Thursday, when Doherty’s demolition contractor obtained a valid license as a lead paint removal contractor. Asked why it took so long, Doherty blamed “state bureaucracy.” Perhaps a different explanation: Doherty’s demolition contractor still hadn’t completed his license application as of Oct. 1, according to an inspection report by the state Department of Labor Standards, which oversees lead paint removal work.

No lead paint removal license

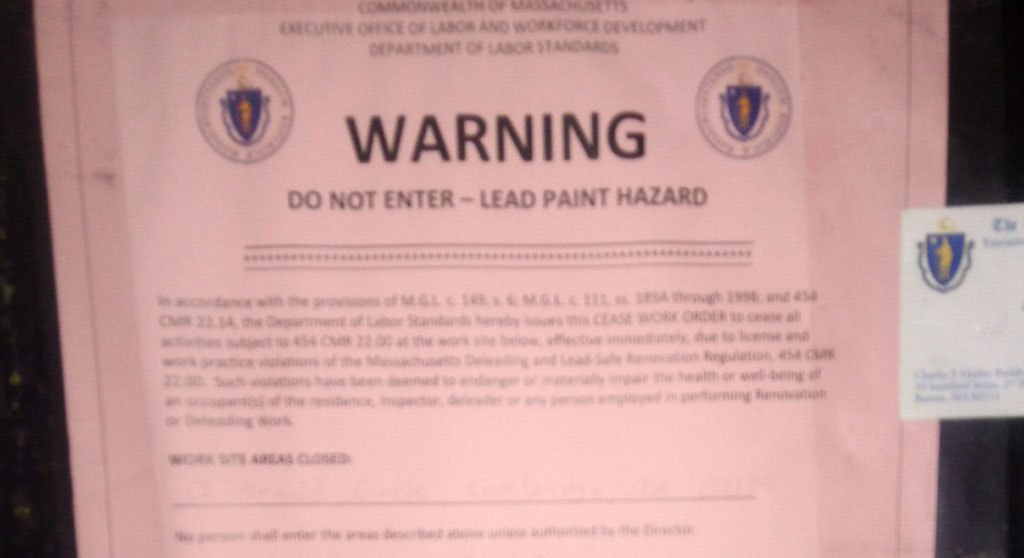

A state warning posted at 12 Arnold Circle warns people not to enter because of a lead paint hazard. (Photo: Sue Reinert)

Still unexplained was why the city approved demolition work in an old building that almost certainly contained lead paint when the contractor didn’t have a valid lead paint removal license. Inspectional Services Department Commissioner Ranjit Singanayagam didn’t return two calls Thursday.

Doherty said Thursday that the demolition contractor, U Call We Haul, had let its license expire but that “it was not like he wasn’t following all required protocols” to handle lead paint materials safely. Doherty acknowledged that there was probably lead paint in the building because of its age. No lead paint tests were conducted.

Lead at very low levels is dangerous to young children; at higher levels it can harm workers. Federal and state rules aim to contain lead dust and debris inside and outside structures and ensure safe disposal of materials containing lead.

Missed steps

The state inspection report conflicted with Doherty’s statement that the license was the only issue and contaminated materials were handled properly. According to the report, there was “a significant amount of demolition-related painted material” on the ground next to a dumpster and a large window lay on the ground, uncontained, in back of the building. Old window frames are often covered with lead paint.

Checked boxes in the report indicated several other lapses: The ground wasn’t covered with a tarp or plastic sheet to catch falling chips of paint; debris and lead dust wasn’t “confined to the immediate work area”; the work area wasn’t cleaned and lead-contaminated materials “securely contained” or properly disposed of at the end of every workday; and there were no warning signs or restricted access to the building.

On Thursday, when the state lifted the work order, at least one window in the building was broken and a large tarp that had previously hung across the front of the structure had come loose from a window at one corner and was drooping on the ground. Doherty said it might take until Monday until work resumes.

Filled 12 units with stuff

The previous owner of the building, Kenneth Krohn, 81, bought it in 1974 for $95,000 but gradually filled up much of the 12-unit space with his papers, books and other possessions as other tenants moved out. Krohn had an improbable career that included a doctorate in mathematics, a business selling software to the U.S. government, a federal prison term for extortion and a law degree (although he couldn’t practice law because of his criminal record).

.

In 2011, fire and building inspectors ordered Krohn to clear out the building and correct safety violations; he said he couldn’t meet their deadlines because of his infirmity and lack of money. The city ordered utilities turned off, and Krohn and his wife moved to a different Cambridge apartment. After little progress, in 2016 the city sued Krohn and later persuaded a judge to put the building under the control of a receiver who would correct the violations.

Resisting affordability rules

The receiver instead sought a buyer to develop the property. The first candidate withdrew after city officials ruled that any new development would have to include two affordable units out of the total of 12, and the Board of Zoning Appeals upheld the decision.

Doherty, the second candidate, agreed to buy the building for $4.6 million and pay Krohn an additional $1 million if a judge overturned the city’s affordable housing ruling. It took months more in court to clear the way for Doherty to buy 12 Arnold Circle on July 24.

Krohn and Doherty have asked a Land Court judge to reverse the city ruling. Krohn is attacking the ordinance itself, saying it is a form of outlawed rent control. Doherty has echoed his argument and also contends that the ordinance, even if legal, doesn’t apply to the building.

Arguments are scheduled in Land Court on Oct. 31.

This post was updated Oct. 12, 2019, to correct a date that had been misidentified on the state’s order to stop work at 12 Arnold Circle. It was updated Oct. 14, 2019, to embed the state inspection report.